By Thomas L. Friedman

Funny country, Lebanon. The minute one army packed up and rushed out, another one swaggered in and took its place. There always seemed to be someone knocking on the door to get in—and someone inside dying to get out. Unlike the PLO and the Israelis, though, the U.S. Marines came to Beirut as “peacekeepers”; they even had a list of ten rules governing when they could fire their weapons, to prove it.

Whenever I think back on the Marines’ sojourn in Lebanon, which lasted from August 1982 until February 1984, I am reminded of a remarkable scene in Tadeusz Borowski’s book about the Nazi concentration camps, This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentleman. Borowski, a Polish poet and political prisoner of the Nazis, Described how, at the end of World War II, a large group of Auschwitz inmates got hold of a Nazi SS guard and began to rip him apart, just as their concentration camp was being liberated by American GI’s.

“At last they seized [the SS guard] inside the German barracks, just as he was about to climb over the window ledge,” wrote Borowski. “In absolute silence they pulled him down to the floor and panting with hate dragged him into a dark alley. Here, closely surrounded by a silent mob, they began tearing at him with greedy hands. Suddenly from the camp gate a whispered warning was passed from one mouth to another. A company of [American] soldiers, their bodies leaning forward, their rifles on the ready, came running down the camp’s main road, weaving between the cluster of men in stripes standing in the way. The crowd scattered and vanished inside the blocks.”

But not without the Nazi guard. The prisoners dragged the German soldier inside their blockhouse, put him on a bunk, covered him with a blanket, and then sat on top of him—looking innocent and waiting for the American soldiers to show up.

“There was a stir at the door,” wrote Borowski. “A young American officer with a tin helmet on his head entered the block and looked with curiosity at the bunks and the tables. He wore a freshly pressed uniform; his revolver was hanging down, strapped in an open holster that dangled against his thigh … . The men in the barracks fell silent . . . . “’Gentlemen,’ said the officer with a friendly smile . . . . ‘I know, of course, that after what you have gone through and after what you have seen, you must feel a deep hate for your tormentors. But we, the soldiers of America, and you, the people of Europe, have fought so that law should prevail over lawlessness. We must show our respect for the law. I assure you that the guilty will be punished, in this camp as well as in all the others.’ … The men in the bunks broke into applause and shouts. In smiles and gestures they tried to convey their friendly approval of the young man from across the ocean . . . . The American . . . wished the prisoners a good rest and an early reunion with their dear ones. Accompanied by a friendly hum of voices, he left the block and proceeded to the next. Not until after he had visited all the blocks and returned with the soldiers to his headquarters did we pull our man off the bunk—where covered with blankets and half-smothered with the weight of our bodies he lay gagged, his face buried in the straw mattress—and dragged him on to the cement floor under the stove, where the entire bunk, grunting and growling with hatred, trampled him to death.”

So it was with the Marines in Beirut—good, milk-faced boys who stepped into the middle of a passion-filled conflict, of whose history they were totally innocent and whose venom they could not even imagine. For a few months after the Marines arrived in Beirut the Lebanese natives sheathed their swords, lowered their voices, and sat on their hatreds, while these clean-cut men from a distant land spoke to them about the meaning of democracy, freedom, and patriotism. After a while, though, the speech got boring, and the wild earth beckoned. Unlike the concentration-camp victims of Borowski’s tale, however, the Lebanese would not wait for the American lecture to end before returning to their feuding ways, so familiar, so instinctual.

So the Marines got an education they never bargained for, and like everyone else who went to Beirut, they got it the hard way.

* * *

There was only one Marine sentry—Lance Corporal Eddie Di-Franco—who got a glimpse of the suicide driver who slammed his yellow Mercedes-Benz truck filled with 12,000 pounds of dynamite into the Marines’ four-story Beirut Battalion Landing Team (BLT) headquarters just after dawn on October 23, 1983. DiFranco could not remember the color of the suicide driver’s hair, or the shape of his face. He could not remember whether he was fat or thin, dark-skinned or light. All he could remember was that as this Muslim kamikaze sped past him on his way to blowing up 241 American servicemen “he looked right at me . . . and smiled.”

Sergeant of the Guard Stephen E. Russell never saw the smile, he only heard the roar. He was standing at his sandbag post at the main entrance of the headquarters, when his eye was suddenly drawn to a huge truck circling the parking lot. The driver had revved his engine to pick up speed before bursting through the fence around the complex and barreling straight for the front door. According to Marine Corps historian Benis M. Frank, Russell “wondered what the truck was doing inside the compound. Almost as quickly he recognized it was a threat. He ran from his guard shack across the lobby toward the rear entrance, yelling, ‘Hit the deck! His the deck!’ Glancing over his shoulder as he ran, he saw the truck smash through his guard shack. A second or two later the truck exploded, blowing him into the air and out the building.

Colonel Geraghty was in his office around the corner, checking the morning news reports, when the explosion blew out all his windows. He ran outside only to find himself caught in a cloud.

“I ran around the corner to the back of my building, and, again it was like a heavy fog and debris was coming down . . . and. . . then the fog cleared, and I turned around . . . the headquarters was gone. I can’t explain to you my feelings. It was just unbelievable.”

For me too. It was 6:22 AM and I was sleeping ten miles away in the heart of West Beirut. Despite the distance, though, the explosion of the Marines’ headquarters shook us out of our sleep. At first Ann and I thought it was an earthquake. There had been a tremor a few months earlier that had wiggled the house the same way. Ann and I did what we always did in such situation: we lay perfectly still in bed waiting to hear if there were sirens. No sirens meant that it was not an explosion, not an earthquake, but just one of a thousand sonic booms Israeli jets set off over Beirut. It took about a minute before the sirens began to wail from every direction. It was too early for me to track down my assistant, Mohammed, so Ann and I hopped into our Fiat and followed the first fire engine we came across. Careening through Beirut’s empty streets, the fire truck eventually led us to the French paratroop barracks, a ten-story apartment block that had been completely blown apart by a suicide bomber who had driven into the underground garage before detonating his car bomb. After I had interviewed people there for about an hour, someone mentioned that they had heard the Marines also “got a rocket,” so several of us leisurely rode over to see the Marines, only to find them staggering about with bloodied uniforms, picking through what was the BLT building, where that afternoon there was supposed to have been an outdoor barbecue—Americanstyle. Within hours of the blast, rescue teams using pneumatic drills and blow torches had begun working furiously on the mound of broken concrete pillars, trying desperately to pry out the dead and wounded. Their efforts were hampered, though, by the fact that unidentified snipers kept firing on the relief workers.

Having come to Beirut to protect the Lebanese, the Marines now seems to be the ones needing protection. As a Lebanese friend put it, “It’s like diapers inside diapers.”

Much of the discussion in the wake of the Marine headquarters bombing would focus on why the Marines did not have an extra barrier here and an extra guard post there to prevent such a suicide attack. The explanation is not a technical-security one but a political-cultural one. The Marines had come to Beirut with such good intentions that it took them a long time to realize (and some of them never did realize) that in being forces by their superiors in Washington to support Amin Gemayel they had become a party to the age-old Lebanese intercommunal war. Shortly after the BLT explosion, I wrote a piece for the Times in which I argued that the Marines had turned into just another Lebanese militia. The Marine spokesman in Beirut cut the article out and put it up on his bulletin board, where other Marines scribbled obscenities all over it, such as “Fuck You, Tom” and “Thanks, Asshole.” Even once they recognized that they were embroiled in a tribal war, however, the Marines failed to take all the necessary precautions against something as unusual as a suicide car bomber, because such a threat was outside the boundaries of their conventional American training. Lance Corporal Manson Coleman, an enormous Marine with a warm smile and American small-town politeness, serves as sentry in Beirut. He told me one day shortly after the Marine headquarters bombing, “We used to get reports all the time about different things terrorists were supposed to be planning against us. One day they said we should look out for dogs with TNT strapped to their bellies. For a few days we were shooting every dog around. Imagine, someone would stoop so low as to have dogs carrying TNT. Now, we have some ingenious ways of killing people, but we are restricted by the Geneva Conventions. Well, these people over here never had any conventions.”

Colonel Geraghty, a taut, controlled man who always evinced an air of real decency, was no better prepared for Beirut’s surprises than his men. But who could blame him? He was caught in the middle of two political cultures totally missing each other: there was no course on Beirut at Camp LeJeune and there were no rules of engagement among the Lebanese. When Colonel Geraghty was asked whether he ever anticipates a suicide attach, he was categoric in his answer: “No, no. It was new, unprecedented. We had received over 100 car-bomb threats—a pick-up truck, ambulances, UN Vehicles, myriad types. Those . . . things we had taken appropriate countermeasures toward. But never the sheer magnitude of the 5-ton dump truck going 50—60 miles an hour with an explosive force from 12,000 to 16,000. [That] was simply beyond the capability to offer any defense. When was the last time you heard of a bomb that size?”

Colonel Geraghty then added, “There may have been a fanatic driving that truck, but I promise you there was a cold, hard, political, calculating mind behind the planning and execution of it.”

Whether that mind was Syria’s or Iran’s or both together will never be known for certain, but American intelligence officials who have seen all the evidence are convinced today that one of the two must have been involved. Which brings up the other reason the Marines were caught unprepared: they were set up. While the Marines were victims of their own innocence, they were even more the victims of the ignorance of the weak, cynical, and in some cases venal Reagan Administration officials who put them into such an impossible situation. Reagan, Shultz, McFarlane, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, and CIA Director William Casey will all have to answer to history for what they did to the Marines. By blindly supporting Amin Gemayel, by allowing Israel a virtually free hand to invade Lebanon with American arms and by not curtailing Israel’s demands for a peace treaty with Beirut, the Reagan Administration had tipped the scales in favor of one Lebanese tribe—the Maronites—and against many others, primarily Muslims. Washington was helping to inflict real pain on many people, and there would have to be a price to pay for that. I will never forget that as I left my apartment house on the morning of the Marine headquarters disaster, a group of Lebanese were playing tennis on the clay court next door. The explosion had probably shaken the ground from under their feet, but it did not interrupt their set. It was a though they were saying, “Look, America, you came here claiming to be an honest broker and now you’ve taken sides. When you take sides around here, this is what happens. So go bury your dead and leave us to our tennis.”

* * *

In the wake of the Marine bombing, the Italian ambassador to Lebanon, Franco Lucioli Ottieri, remarked to me, “You know how they say people are always fighting the last war? Well, you Americans have been preparing yourselves for the confrontation on the Eastern front. That’s fine. The Eastern front with the Soviet Union is now secured. But you are deplorably unprepared for the war in the Third World. You are like a big elephant. If you are up against another elephant, you are fine. But if you are fighting a snake, you have real problems. Your whole mentality and puritanical nature hold you back. Lebanon was full of snakes.”

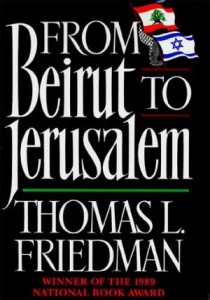

Excerpted from From Beirut to Jerusalem by Thomas L. Friedman.

Copyright © 1989 by Thomas L. Friedman.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the publisher.

THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN is an internationally renowned author, reporter, and columnist—the recipient of three Pulitzer Prizes and the author of multiple bestselling books, among them From Beirut to Jerusalem and The World Is Flat.

He was born in Minneapolis in 1953, and grew up in the middle-class Minneapolis suburb of St. Louis Park. He graduated from Brandeis University in 1975 with a degree in Mediterranean studies, attended St. Antony’s College, Oxford, on a Marshall Scholarship, and received an M.Phil. degree in modern Middle East studies from Oxford.

After three years with United Press International, he joined The New York Times, where he has worked ever since as a reporter, correspondent, bureau chief, and columnist. At the Times, he has won three Pulitzer Prizes: in 1983 for international reporting (from Lebanon), in 1988 for international reporting (from Israel), and in 2002 for his columns after the September 11th attacks.

Friedman’s first book, From Beirut to Jerusalem, won the National Book Award in 1989. His second book, The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization (1999), won the Overseas Press Club Award for best book on foreign policy in 2000. In 2002 FSG published a collection of his Pulitzer Prize-winning columns, along with a diary he kept after 9/11, as Longitudes and Attitudes: Exploring the World After September 11. His fourth book, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century (2005) became a #1 New York Times bestseller and received the inaugural Financial Times/Goldman Sachs Business Book of the Year Award in November 2005. A revised and expanded edition was published in hardcover in 2006 and in 2007. The World Is Flat has sold more than 4 million copies in thirty-seven languages.

In 2008 he brought out Hot, Flat, and Crowded, which was published in a revised edition a year later. His sixth book, That Used to Be Us: How American Fell Behind in the World We Invented and How We Can Come Back, co-written with Michael Mandelbaum, was published in September 2011.