by James E. Wright

By the fall of 1968, a majority of Americans agreed that Vietnam was the nation’s major problem—as they had pretty consistently affirmed for the previous three years. Increasingly, there was a mood that it was time to do something about this problem—and some emerging if vague consensus on what this might be. In May, 41 percent of those polled by George Gallup had said they were “hawks” and an equivalent number described themselves as “doves.”

Just a year earlier, the self-identified hawks had dominated 49 percent to 35 percent. Gallup’s polls indicated that by a margin of 64 percent to 26 percent, Americans approved of the bombing halt that President Johnson had announced back in March. In that same month, by a margin of 69 percent to 21 percent, Gallup’s sample agreed with an approach whereby the United States would withdraw troops and leave the South Vietnamese to carry on the fighting—with American supplies and economic support. In August and October 1968 polls, those surveyed indicated by consistent margins of 66 percent to 18 percent that they would be more likely to support a candidate who would turn over more of the fighting to the South Vietnamese and begin to withdraw American troops.

It was clear by 1968 that the cold war consensus that had supported American engagement in Vietnam had eroded. In many ways the polls were ahead of the candidates—or at least were ahead of any explicit plans the candidates articulated. The presidential contenders had no chance to try to explore positions in a presidential debate format since Nixon would not agree to engage in debates.

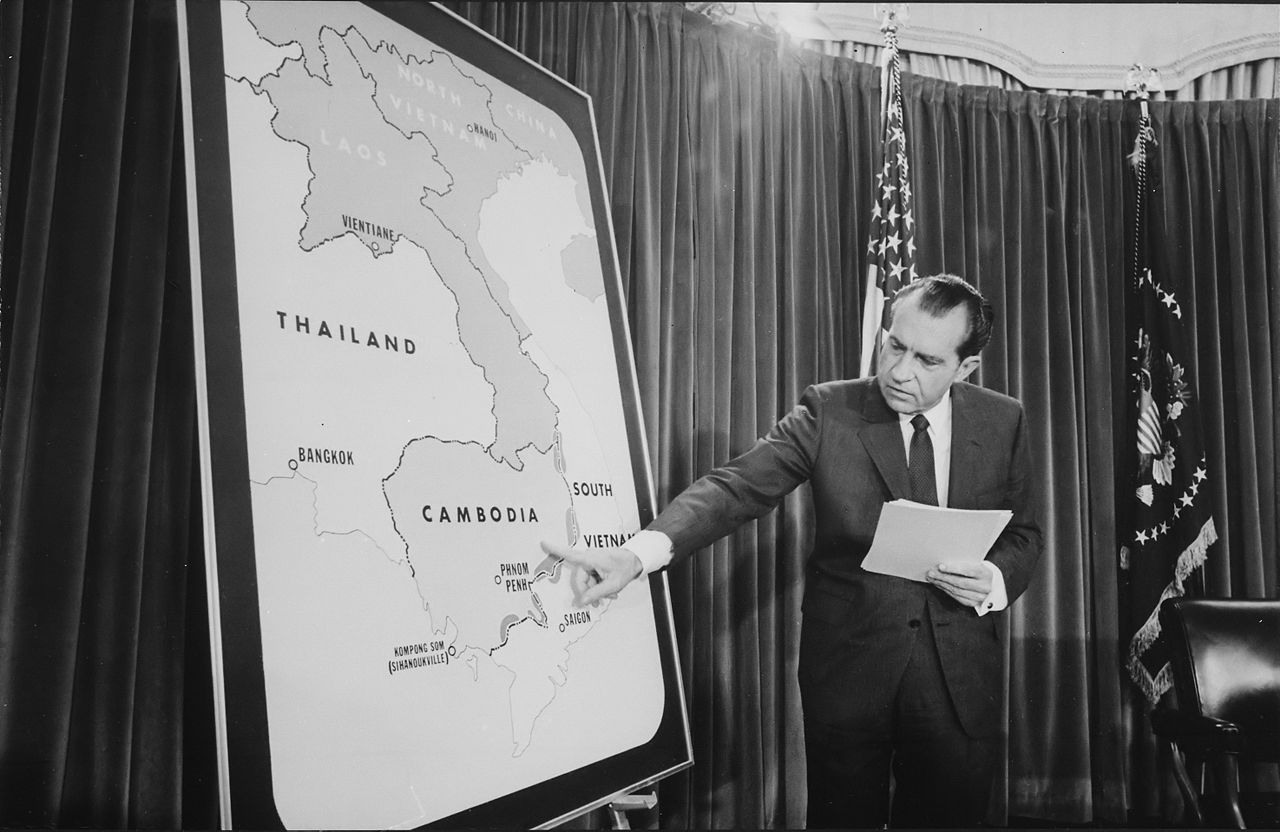

Nixon’s Vietnam strategy, as previewed in the election campaign, had several components: Encourage the South Vietnamese to assume more responsibility for the combat operations in the South, begin to draw down or at least draw back U.S. troops, keep the pressure on the North Vietnamese and try to negotiate a treaty with them, and try to solicit Soviet help in accomplishing this. It appealed to many, even if it was not fully articulated. Nixon also proposed ending the draft at the conclusion of the war and moving to a volunteer army.

Importantly, the only candidates who talked of a traditional military victory in Vietnam were George Wallace and Curtis LeMay. And the pledges of these two men were more rhetorical than a practical plan for how to accomplish this. Governor Wallace insisted that the military should be encouraged to use “all of the military ability we have, including air and naval power” to secure victory— but he took the nuclear option off the table. On November 2, The Saturday Evening Post editorialized that only Wallace suggested he would increase the fighting. The editors concluded that Humphrey and Nixon seemed to combine a stay-the-course policy with one of negotiated withdrawal. And “each candidate seems to be basing his campaign on the assumption that nobody really believes what he is saying.” Since 1965, the sharp anticommunist, win-the-war-quickly rhetoric had cooled as the problems became more clear and confidence in a quick resolution waned. For most Americans in the fall of 1968, the ambivalent 1965 goals in Vietnam had been reduced to how best to extricate America from the war.

accomplish this. Governor Wallace insisted that the military should be encouraged to use “all of the military ability we have, including air and naval power” to secure victory— but he took the nuclear option off the table. On November 2, The Saturday Evening Post editorialized that only Wallace suggested he would increase the fighting. The editors concluded that Humphrey and Nixon seemed to combine a stay-the-course policy with one of negotiated withdrawal. And “each candidate seems to be basing his campaign on the assumption that nobody really believes what he is saying.” Since 1965, the sharp anticommunist, win-the-war-quickly rhetoric had cooled as the problems became more clear and confidence in a quick resolution waned. For most Americans in the fall of 1968, the ambivalent 1965 goals in Vietnam had been reduced to how best to extricate America from the war.

During the fall, Life magazine sent its Vietnam correspondents around the country, where they interviewed some 300 men and women in the service about the election and the war. Acknowledging that many of the men and women they interviewed were not yet twenty-one and therefore ineligible to vote, they learned that these citizens were well informed about the election—if not at all convinced that its results would make any difference. Most strongly opposed any bombing halt because they believed that it was essential to keep the pressure on the enemy—and to complicate enemy efforts to keep pressure on the American troops. They still talked about the need to stand up to communism in Vietnam to prevent the fight from moving to American streets. There seemed to be a preference for Richard Nixon as a new face—they knew little about the “old Nixon.” And there was a strong affection for Bobby Kennedy—and surprising sympathy for Lyndon Johnson. But finally they were focused on their task: “The only thing anyone here is rabid about is getting out alive.”

The Nixon team had worried through the campaign about what they called an October surprise. They feared that President Johnson might have some new initiative that would throw off their momentum. They were right. On October 31, Johnson announced a full bombing halt in the North and said that negotiations to end the war would begin immediately in Paris. Hanoi had finally agreed to allow South Vietnam to participate in the talks in exchange for the bombing halt. The news of peace talks had the potential to influence the election results. Except that the convening of the talks was delayed when South Vietnam refused to join. Johnson was furious. And he was more than furious when he learned, through FBI wiretaps, that the Nixon team, working with Anna Chennault, had urged the Saigon government not to participate. Mrs. Chennault was the Chinese-born widow of the American World War II hero Army Air Force general Claire Chennault. She was a wealthy businesswoman and a Republican Party loyalist. She had assured South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu that South Vietnam would have far greater success in negotiations convened by the Nixon administration. Lyndon Johnson threatened to go public with information that he considered treasonous. But he finally pulled back— doing so would have involved admitting that he was tapping the phones of the Nixon team.

On November 5, 1968, American voters elected Richard Milhous Nixon as the thirty-seventh president of the United States. Mr. Nixon received a plurality, 43.4 percent of the popular vote to Hubert Humphrey’s 42.7 percent and George Wallace’s 13.5 percent. Nixon enjoyed a half-million-vote edge out of nearly 73 million cast. But he won a more significant Electoral College victory with 301 electors to Humphrey’s 191 and Wallace’s 46.

The election returns almost certainly demonstrated that the nation was ready to do something about the Vietnam War. But neither the campaign nor the election provided a policy direction— except that it was pretty clear that an increase in troop levels and an escalation of the ground war were not an option. As far as most Americans were concerned, that phase of the war seemed to be drawing down. Notwithstanding this, in Vietnam that phase of the war continued unabated. As the American election results came in late on the night of November 5, it was midday the next day in Vietnam. On November 6, 33 Americans died in Vietnam. As Richard Nixon assembled his transition team to prepare for the transfer of power, part of this package was the assumption of responsibility for the war in Vietnam.

JAMES WRIGHT is President Emeritus and Eleazar Wheelock Professor of History Emeritus at Dartmouth College and the author or editor of several books, including Those Who Have Borne the Battle. His efforts on behalf of veterans and education have been featured in the New York Times, Boston Globe, NPR, and more. He serves on the Boards of the Semper Fi Fund, the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, and the Campaign Leadership Committee for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund Education Center. He lives in Sunapee, NH.