By Trevor Royle

Following the victory in North Africa, the next stage of the war against the Axis forces involved the capture of Sicily as a precursor to an invasion of Italy, a move the Allies hoped would lead to the final securing of the Mediterranean with its vital maritime routes. However, even before the operation began, its planning was dogged by disagreements and acrimony. U.S. General George Marshall still wanted to press ahead plans for the invasion of France and northern Europe. He favored a hard hit to Nazi Germany as the only way to win the war and did not want U.S. forces tied down in interminable operations in the Mediterranean, which he regarded as a strategic backwater. At the same time, Churchill remained preoccupied with attacking what he called on numerous occasions the “soft underbelly of Europe,” both as a means of engaging the Germans and knocking Italy out of the war. As described by his biographer Martin Gilbert, Churchill’s aim was “to persuade the Americans to follow up the imminent conquest of Sicily by the invasion of Italy at least as far as Rome, and then to assist the Yugoslav, Greek and Albanian partisans in the liberation of the Balkans, by air support, arms and coastal landings by small Commando units.” At the Casablanca conference in 1943, there had been a marked divergence of opinion over the choice of Sicily (code-named “Husky”); Sardinia or Corsica was preferred by some planners. Then, of course, there was the slow rate of progress in Tunisia: senior commanders earmarked for Operation Husky, including Montgomery and U.S. General George Patton, were tied up in the fighting there until its final stages. As Montgomery protested to Harold Alexander on April 4, the day before the assault on Wadi Akarit: “It is very difficult to fight one campaign and at the same time to plan another in detail. But if we can get the general layout of husky right other people can get on with the detail.” Later, as the planning became more confused and less focused, Montgomery would complain that the operation was “a dog’s breakfast” (a favorite expression to describe his disgust at muddled thinking) that broke every basic rule about fighting the Axis. He felt it was doomed due to a failing that he always characterized as “a lack of grip.” It is against that background of uncertain aims and Allied bickering that the British and U.S. roles in the Sicilian campaign should be seen.

In the middle of April 1943, having been relieved of command of U.S. II Corps, Patton returned to Casablanca to prepare the U.S. I Armored Corps for the forthcoming invasion. Ostensibly, as one of the invasion commanders—Montgomery, in charge of the British Eighth Army, was the other—Patton should have played a leading role in the planning of Husky, but so bitter were the British interservice rivalries and the lack of cohesion that he was left out in the cold. Command of the operation had been given to Alexander (Fifteenth Army Group), under U.S. Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s nominal direction, but apart from Patton, all the senior commanders were British. The Allied naval forces were commanded by Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham of the Royal Navy, while the air forces were under the direction of Air Chief Marshal

Sir Arthur Tedder of the Royal Air Force. Not only were the Americans effectively frozen out of the senior command structure, but existing rivalries among the British commanders meant that the invasion plan was prolix in approach and protracted in development and execution. In the original outline, Alexander’s staff put forward proposals for an amphibious assault along the Sicilian coastline, with the attacking forces coming from the western and eastern Mediterranean. While this had the advantage of surprise—if it could be mounted quickly against what was then a weakly defended island—the operation carried with it the danger of being piecemeal and lacking in concentration. Another drawback was the failure to integrate the air element into the planning. Tedder had insisted that his squadrons would require the land forces to seize airfields for his strike aircraft so that air cover could be provided throughout the operation. The ensuing round of discussions were marred by undignified arguing and prevarication, and the deadlock was only broken by the intervention of Montgomery, who was quite capable of defending his corner and whose reputation as a battlefield commander had been greatly enhanced by his victories in North Africa. He refused to carry out the original plan, which obliged him to produce an alternative solution. Although Montgomery had given his tentative blessing to the first set of plans, he now opposed them vehemently, leaving Alexander with the option of either firing him for his presumption or agreeing with what he had to say.

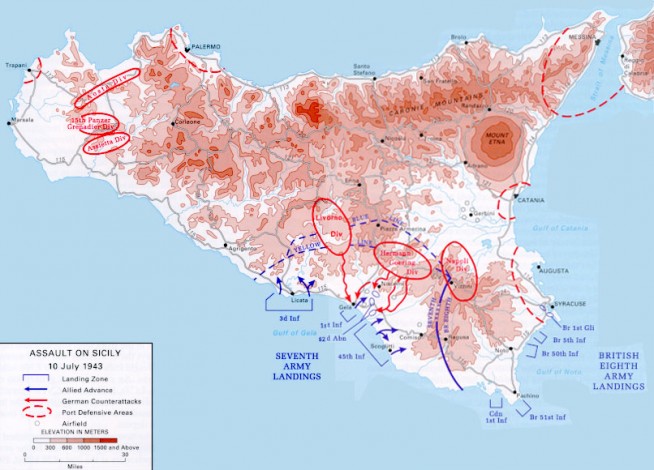

On May 2, the revised plans were accepted. Montgomery’s proposal called for an invasion by the Eighth Army, launched between Syracuse and the Pachino peninsula on the island’s southeastern coast, while Patton’s I and II Armored Corps, shortly to be renamed the U.S. Seventh Army (to give him parity with Montgomery) would land on a 40-mile front along the southern coast between Gela and Scoglitti and Licata on the left flank. There would also be an airborne assault carried out by the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division and the British 1st Airborne Division to attack targets in the inland area and to secure the landing grounds. For this first major combined land, sea, and air operation against a European target, overwhelming force would be used: 478,000 troops (250,000 British; 228,000 American) and 4,000 Allied aircraft. The landing forces would consist of an Eastern Naval Task Force under British command (795 warships and 715 landing craft) and a Western Naval Task Force under U.S. command (580 warships and 1,124 landing craft). Once ashore. Montgomery planned to create a bridgehead to secure the ports of Syracuse and Licata before moving rapidly north to Messina, while Patton’s forces guarded his left flank.

On May 4, Alexander wrote a letter to Eisenhower at his headquarters in Algiers outlining the new plan, which seemed to suggest that the overall commander on the ground would be Montgomery. This was, in fact, his express request:

As a result of acceptance by all concerned of present plan, land operations by British and American Task Forces really become one operation. Each will be dependent on the other for direct support in the battle and their administrative needs. As time is pressing, I am convinced that the co-ordination, direction and control both tactically and administratively, must be undertaken by one commander and a joint staff.

Alexander did not say that the one commander would be Montgomery. He did not have to; Eisenhower would have had little difficulty guessing, and he noted Alexander’s comment that Montgomery had offered to be as helpful as possible “in overcoming the problems facing the American Task Force.” As placing U.S. troops under British command would be deleterious to American public opinion, a further compromise was introduced to allow the British and U.S. generals to retain their independent commands after landing. The arrangement seemed to suit Patton, who was anxious to get back into battle. Three days later he wrote in his diary: “The new set up is better in many ways than the old. . . . Monty is a forceful selfish man, but still a man, I think he is a far better leader than Alexander.”

After the operational plan had been set, the invasion of Sicily was one of the many topics discussed at the Trident Conference held in Washington between May 11 and 25. Described as the most ill-tempered of all the wartime Allied meetings, Trident pitted British against U.S. interests, with both sides at loggerheads over future Allied strategy. At the first meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staffs, Marshall said that he regarded the North African strategy “with a jaundiced eye” and reiterated his preference for “cross-Channel operations for the liberation of France and advance on Germany.” Brooke was equally adamant that the Allies should exploit the victory in Tunis with the invasion of Sicily, followed by the elimination of Italy from the war. Although the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff acknowledged that the “Americans wanted to close down all operations in Med after capture of Sicily,” a compromise was reached when the British agreed to take part in an Allied cross-Channel invasion the following year, the price being U.S. approval for further operations in Italy (although the final report made no mention of this commitment).

The date of the Sicilian invasion was fixed for July 10, but the delay provided time for the Germans and Italians to reinforce the island. During the campaign in North Africa, Sicily was defended by General Alfredo Guzzoni’s Sixth Army, which consisted of four field divisions and six badly equipped and undermanned coastal defense divisions. By the end of June, these had been supplemented by a German panzer division and a new division formed out of reinforcements bound for North Africa (the 15th Panzergrenadier). Later these would be bolstered by the German 1st Parachute Division and the 29th Panzergrenadier Division, both drawn from France. Guzzoni’s plan was to allow the weaker coastal divisions to bear the brunt of the Allied assault while the remaining forces, including the Germans, regrouped for a counterattack to drive the enemy back to the beaches.

Although Montgomery had taken into consideration the growing strength of the Axis defenses, Ultra intelligence intercepts suggested that the Italian soldiers’ morale was low, and there was good reason to believe that the landings would be virtually unopposed. On the day itself, bad weather conditions created problems, but by late afternoon on July 10, Montgomery’s two corps (XIII and XXX) were safely ashore between Pozallo and Syracuse to the east, while Patton’s forces had taken the beaches between Cape Scaramia and Licata to the southwest. Within a few hours, all Allied divisions were ashore and the port of Syracuse had been captured intact. Forty-eight hours later, Montgomery believed that the route to Messina was open and that Axis resistance would crumble as his forces advanced up the eastern littoral:

The battle in sicily is a battle of key points. The countryside is mountainous and the roads poor. The few big main roads are two-way and very good; these run North-South and East-West, and once you hold the main centres of inter-communication you can put a stranglehold on enemy movement and so dominate the operations. As we drive forward on the main axes so the enemy tries to escape down the side lateral roads; but they cannot actually get away, and are then rounded up in large numbers. On the right flank—the sea flank—the Navy moves along keeping touch with the land battle and bombards effectively towns and villages where resistance is being offered. Fought in this way the battle is simple and the enemy is being forced back by our relentless pressure. On my left the American 7th Army is not making very great progress at present; but as my left [XXX] Corps pushes forward that will tend to loosen resistance in front of the Americans.

Had Montgomery confined his thinking to his diary, all might have been well, but he sent a similar signal to Alexander, broadly hinting that he was in pole position to take Messina and that the Americans should play a supporting role by covering his left flank. Montgomery had been lulled into thinking that the lack of immediate resistance meant that the battle was as good as won. He was wrong, and by planting in Alexander’s mind the idea that he should lead the advance on Messina, with the U.S. forces playing a subsidiary role, Montgomery had created the conditions for an open clash with Patton. Their rivalry was to be one of the hallmarks of the Sicilian campaign.

The weather, too, continued to be a factor. Following the landings, it deteriorated with fresh summer storms followed by hot, stifling temperatures, hampering a rapid advance. Then there was an unforced disaster involving the Allied airborne assault’s air landing and parachute troops. On the night of the operation, the winds were up to 35 miles per hour, and many of the British gliders had been shot down by Allied fire or landed in the sea before they reached their targets. Of the total force of 144 gliders, only 54 landed in Sicily; and of that number, only a dozen reached the correct landing grounds. The paratroopers of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division fared equally badly. Either they were dropped in the wrong place or failed to reach the dropping zone over the southern part of the island after their transports got lost or were fired on by Allied shipping—a direct result of the lack of inter-service planning.

It was at this crucial early stage that Operation Husky began to unravel. As understood by Alexander, the British Eighth Army would provide the sword thrust toward Messina while the U.S. Seventh Army would act as its shield to block any counterattack. While this might have worked in theory, it made little sense in practice. First, there was no plan to allow Patton and Montgomery to work in concert. Second, the division of effort took no account of the island’s difficult topography. Third, Alexander did not impose his will on the battle, a failure that allowed two headstrong army commanders on the ground to act independently of one another. Last, Alexander did not grasp that the Americans who fought in Sicily were very different from the tyros who had given such a poor performance in North Africa.

Unusually for him, Patton did not question how Montgomery had taken control of the operation, and he agreed to the plan without challenging it. The most salient explanation was the sudden deterioration in his relationship with Eisenhower, who had blamed him, unfairly, for the friendly-fire incidents involving the airborne forces. With the fear of dismissal hanging over him, Patton was in no position to question an unwise demand from Montgomery to hand Highway 124 over to British control, the main highway leading north. At the time, it was partially controlled by the U.S. 45th Division, which was making good headway in its advance from Vizzini toward Caltagirone. Now they were forced to make way for Montgomery’s forces. Not only did the request deepen American mistrust of British motives, it was a tactical mistake, as the removal of the U.S. forces prevented Lieutenant-General Omar N. Bradley from deploying U.S II Corps northward to cut the island in half. If Bradley had been allowed to push ahead, there was every chance that the German 15th Panzergrenadier Division would have been cut off from its escape route toward Messina. It was a move that was later deprecated by the British corps commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Oliver Leese:

I often think now that it was an unfortunate decision not to hand it [Highway 124] to the Americans. Unknown at any rate to XXX Corps, they were making much quicker progress than ourselves, largely owing, I believe, to the fact that their vehicles all had four-wheel drive. They were therefore far better equipped to compete quickly with the endless deviations with which we were confronted, as a result of the destruction of every bridge by the Germans. We were still inclined to remember the slow American progress in the early stages in Tunisia, and I for one certainly did not realise the immense development in experience and technique which they had made in the last weeks of the North African campaign. I have a feeling now that if they could have driven straight up this road, we might have had a chance to end this frustrating campaign sooner.

That observation was written with the benefit of hindsight, but as expressed by Nigel Hamilton, Montgomery’s official biographer, Leese’s opinion is noteworthy because it provides an insight into the problem facing the ground commanders. Tactical sense suggested that the decision to hand over the highway played into the defenders’ hands by allowing them to regroup, but in the absence of any overall plan, Patton was forced to concede to the British request. As it was, the Eighth Army did not require use of the entire highway, but this was not explained to the Americans, who thought that their role was being usurped at a time of progress.

The boundary-line incident did nothing to create any goodwill between the two armies, but events were about to change. Far from being able to push quickly toward Messina, Montgomery’s forces became bogged down in the breakout from Syracuse. It was unpromising territory, but it had to be secured if the advance was to maintain its timetable. Unfortunately, it was also a countryside made for defense. Towering over the plain was the smoking hulk of Mount Etna, which the enemy used to good effect to observe the Allied movements. The Germans also enjoyed air superiority, and although some airfields had been captured by the Allies, it took time for aircraft to arrive and mount sorties against the enemy. Topographical considerations prevented Montgomery from utilizing his armor and artillery, and the lack of a decent road system meant that the infantry had to return to slogging by foot. The presence of civilians in the battlefield areas was also a hindrance. In short, after the freedom of movement enjoyed in North Africa, the Eighth Army found itself hemmed in, and the Plain of Catania proved to be a difficult hurdle. On the night of July 13, an airborne operation by the 1st Parachute Brigade failed to take the vital bridges at Primasole, and as a result, Catania remained in enemy hands.

Compounding the problems for the British, Leese’s XXX Corps ran into fierce opposition as it moved over the mountainous terrain toward Enna and Leonforte, while XIII Corps was halted in its tracks on the road to Catania. It was almost as if the Axis defenders knew Montgomery’s plan, and their unexpected resistance forced him to hook inland around the obstacle of Mount Etna. The operation was not an immediate success: the Canadian 1st Division clashed with the German 15th Panzer Division and was forced to wait for reinforcement from the 51st (Highland) Division. This delay gave Patton the chance to do something different while his British allies were distracted by their sudden reversals. Taking the view that there was enough room on the island for both armies to operate, Patton approached Alexander on July 17 with a proposal to move westward to capture the port of Agrigento. Permission was granted, providing that the Americans did not provoke a major battle that would threaten Montgomery’s flank. Patton agreed, in the interests of maintaining Allied solidarity, but the unexpected decision provided him with the opportunity for greater U.S. involvement in the battle. While the U.S. 3rd Division attacked Agrigento, the rest of U.S. II Corps moved quickly north toward the coast to take the ports of Termini Imerese and Palermo.

On paper, the operation to seize the Sicilian capital served no useful purpose, but it did impress Alexander, by demonstrating that the U.S. Seventh Army was now a fighting force worthy of his attention. Two days later, the U.S. 45th Division reached the northern coast; Sicily was cut in half, and Patton was well placed to consider the next target—the prize, Messina. On July 25, Montgomery asked him to fly to Syracuse to decide the next phase of the operation. It was the first time that the two leaders had conferred since Husky began, and the outcome of their deliberations would be decisive in confirming Patton’s growing reputation as a battlefield soldier.

That conference and the one that followed three days later also gave rise to the much-repeated story that Patton and Montgomery were involved in a heated rivalry to be the first general to take Messina. It made for good drama at the time and has been regularly cited, mainly in U.S. accounts, but it is in fact complete nonsense. By that stage in the battle, Montgomery realized that the Eighth Army could not take Messina single-handedly, and he therefore gave Patton permission take control of both the major roads north of Etna. He noted the revised thinking in his diary on July 28: “On my left I urged that 7 American Army [sic] should develop with two strong thrusts. (a) With two Divisions on the axis nicosia-troina-randazzo. With two Divisions on the axis of the North coast road to messina. This was all agreed.”

For the next stage of the war, Montgomery’s thinking was sound. Ahead lay the invasion of Italy, and he was not prepared to sacrifice his men’s lives when the U.S. forces were equally well placed to attack Messina. Two days before meeting Patton, he informed Alexander of his intentions: “Consider that whole operation of extension of war on to mainland [Italy] must now be handled by Eighth Army as once sicily is cleared of enemy a great deal of my resources can be put on to mainland.” Under those circumstances, it made better sense to rest his own men and to pass the main thrust of the battle on to the U.S. Seventh Army. So Messina was handed on a plate to an astonished Patton, who was forced to realign his forces for an attack along the northern coast of Sicily as the enemy forces retreated to safety over the straits to southern Italy.

Although Patton did not know it, the race for Messina was over almost before it had begun. The Germans were not prepared to hand it over without a struggle, but steps had already been taken to surrender Sicily. The commander-in-chief of the Axis forces, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, was determined not to repeat the defeat in Tunisia, and shortly after the Allied landings, he decided to pull out his forces to make them available for the defense of Italy. His plan was simple but effective. General Hans-Valentin Hube, now commander of the Axis ground forces, was ordered to form a strong defensive perimeter around Messina and to prepare for an evacuation in the second week of August. Every Luftwaffe aircraft within range was put into the air to provide cover for the dangerous crossing, while large antiaircraft batteries were deployed on both sides of the straits. Kesselring was taking no chances, as he needed the Axis forces and all their equipment to counter the next stage of the battle. The German decision to retreat was also hastened by the sudden fall from power of the Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini on July 25. His sudden resignation and subsequent arrest made it entirely possible that Italy would withdraw from the war.

To avoid that eventuality, the Germans prepared to seize power in Italy, and that meant withdrawing quickly and efficiently from Sicily. U.S. forces entered Messina on the evening of August 16 when a fighting patrol from the 3rd Division became the first Allied formation to enter the shattered city, two hours ahead of a British commando force. The next day, a triumphant Patton arrived at Messina, riding in a staff car sporting a three-star pennant with a small convoy behind. At the same time, Montgomery’s forces had pushed north from Catania to complete the operation and but for the road being broken at Taormina, the British 50th Division might have arrived simultaneously with the U.S. forces, which would have taken some of the gloss off Patton’s triumph.

It had taken the Allies the better part of a month to complete the invasion of Sicily, longer than anyone had expected, and it had been a hard slog. Much of the fighting was over difficult terrain in sweltering weather conditions, and the enemy, particularly the German panzer soldiers, had proved formidable opponents. The end results were that Sicily became a jumping-off point for the forthcoming invasion of Italy, the lines of communication through the Mediterranean were secured, and 160,000 Axis troops were killed or taken prisoner. But the victory had come at a price. Kesselring’s evacuation plan worked brilliantly, allowing 40,000 German and 62,000 Italian troops to escape over the Strait of Messina, along with most of their heavy equipment. While Patton was pressing ahead to the port, the imperturbable Germans began an audacious maneuver to transfer men and equipment using a fleet of ferries and landing craft to pull their forces out from under the Allies’ noses. Despite the attentions of the Royal Air Force, only seven ferries and a handful of minor vessels were sunk—a tribute to the intensity and accuracy of the antiaircraft defenses—and to make matters worse, Admiral Cunningham’s warships failed to mount any interdiction missions. Given the fact that the Germans were prepared to sacrifice Sicily to the Allies in advance of the defense of Italy, their successful fighting retreat from Messina helped to turn defeat into a victory of sorts.

By allowing the enemy to retreat so easily from the island, Operation Husky was not an unalloyed success, and all the German divisions were able to take part in the next phase of the operations in Italy. If the Allies had launched the assault two months earlier, they would not have faced the kind of determined opposition that halted the Eighth Army as it fought its way through the plain of Catania. There was still much to learn about Allied cooperation and the need to maintain a unified command on the battlefield without letting matters of national pride interfere. However, it would be wrong to write off the operation as a moderate success that achieved few strategic gains in return for a substantial deployment. Montgomery’s plans for the landings at Gela and Syracuse were a useful forerunner for the cross-Channel operations of the following year, and important lessons were learned about airborne operations. Once again the Germans had suffered defeat, and their panzer forces were seen to be vulnerable. Most importantly of all, from the Allies’ point of view, the U.S. Army emerged as a first-class fighting force, displaying mobility, aggression, and a will to win—virtues which would stand it in good stead in the later fighting in Europe.

Excerpted from Montgomery: Lessons in Leadership from the Soldier’s General by Trevor Royle.

Copyright © Trevor Royle, 2010.

Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

TREVOR ROYLE is a broadcaster and author specializing in the history of war and empire with a score of books to his credit. His previous books include Civil War: The Wars of Three Kingdoms, Crimea: The Great Crimean War 1854-1856, a New York Times Notable Book, Lancaster Against York and Montgomery: Lessons in Leadership from the Soldier’s General. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, a regular commentator on defense matters and international affairs for the BBC and an Editor at The Sunday Herald. He lives in Edinburgh, Scotland.