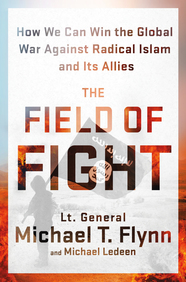

by Lt. General (Ret) Michael T. Flynn and Michael Ledeen

Lt. General (Ret.) Michael T. Flynn spent 33 years as an intelligence officer. Before he was terminated from government service, he served as the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency and the Senior Military Intelligence Officer in the Department of Defense. He has since run for Donald Trump’s Vice Presidential nominee and now gives his account of the mistakes of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars.

Excerpt from Chapter 2: Field of Fight

The Iraq War was the template for what followed in Afghanistan and Syria. Although we were in Afghanistan first and initially “won,” Iraq became the main effort— the priority. Once that happened, we lost sight of what we needed to do in Afghanistan. Despite the great commanders and soldiers we were sending into that theater, Iraq quickly came to consume everything. Practically all resources (at least the good stuff) were diverted to fight an enemy that had nothing to do with the attacks on 9/11. And our enemy was not a foreign army in the conventional sense of war fighting. This was a guerrilla war. The enemy was an extensive network of combatants out to kill us. We were up against a checkerboard of Iraqis, foreign fighters primarily from Arab countries enlisting local tribes, and Iranian killers and intelligence operatives providing the training, funding, and weapons to their friends in Iraq.

We were unprepared for this revolutionary battle.

Our commanders and soldiers needed to know, in granular detail, who we were up against. They needed a clear understanding of the mash-up enemies’ interaction. Were we fighting the remnants of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist state? Was this a national uprising against us, or an alien occupying force? Were there national leaders, or were there so many tribal, ethnic, religious, and regional divisions within the country that we needed very different tactics to establish order?

In traditional warfare, armies determine the winner and loser of battlefield conflict. One side wins and the other side surrenders. There is a victor and a vanquished. Not so in a guerrilla war where, counter intuitively, the better you do— the more enemies you kill and capture— the worse things can get. Just look at the Soviets in Afghanistan. They killed countless Afghan and foreign jihadis. When it was over, there were more enemy fighters than before. Why? The jihadis say that if we kill one of them, ten new fighters rush to fill the void.

As unconventional as the Iraq War was, we mastered it. Afghanistan was a different story. We knew that the Soviets had killed a lot of Afghans, but by the time of their retreat they had created a larger insurgency. It obviously wouldn’t do to simply kill our enemies, even their top leaders. The French had learned this in Algeria and we had some prior experience that confirmed the lesson in the Philippines and Vietnam.

The basic principle of guerrilla warfare is that the people on the ground determine the outcome of the conflict. And when I say “the people on the ground,” I’m not talking about the terrorists. I’m talking about the resident population. These are the people who will eventually choose the winner and the loser. Their decision is dependent on us getting the information we need from them for our war fighters to use, and gaining their support. And their choice depends on several other factors that determine which way they go.

First and foremost, the population does not want to get dragged into the fighting at all. They will stay out as long as they can, until they decide which side is destined to win. Only then are their battle lines drawn.

Notice two things: their decision is not primarily a political, let alone a moral, preference; and the decision is a self-fulfilling prophecy. That’s because they choose their side once they decide who the winners- to-be are. Once they throw their support in that direction, that side gains an unbeatable advantage because “support” means the winners- to-be have the critical intelligence and the indispensable manpower they need to win.

Not that there is no political element involved in this crucial decision; it’s there, but the brutal realities of the war overwhelm their political preferences. Many Iraqis, especially the Sunni tribal leaders in Anbar Province, joined us because they were disgusted by the savagery of al Qaeda. Ironically, they may not have preferred, or even liked, the side they supported. But once convinced it’s the winning side, information flows and support follows. Machiavelli was right when he analyzed this type of strange environment: “It is better to be feared than loved, if you cannot be both.”

Furthermore, the context for picking sides is local, not national or even chosen by regional governments. The decision is made by tribes, clans, and networks. Indeed, the people in one location often made decisions directly contrary to their nearby neighbors just down the road. In practice, it could mean supporting Sunnis in one place and Shi’ites in another.

We weren’t accustomed to thinking in such a way or acting accordingly. We had to change our strategic war- fighting approach. Above all, we had to mesh with the locals. In practice, this meant that the primary focus of the war had to fundamentally shift from ground fighting to intelligence operations. This doesn’t mean killing ended, it simply required a completely different and far more precise attitude to warfare.

The Cold War was a bad model for winning the war in the Middle East. In the Cold War, the Soviet Union was tough to penetrate, and recruiting good informers was difficult and dangerous. But in Iraq and to a lesser degree Afghanistan, we were deployed all over the place, and could talk to most anyone. Eventually, we infiltrated the enemy’s networks. Sometimes this turned out to be extraordinary intelligence— bulletproof intelligence, in fact. We ran informants, we ran deception operations, we ran counter- information operations, and we also ran extremely effective interrogation operations. All of these operations required very simple but very smart technology. However, and more important, they required physical and intellectual courage, superb intelligence analysis, and some really savvy, cunning special operators who understood the enemy and the human geography we were facing at that time.

The breakthrough came in Anbar Province in Iraq, which provided the model for the Surge of U.S. forces, and later shaped our strategy in Afghanistan. In war, things change all the time, and dramatic changes are often overlooked. This is what happened in Iraq in 2006. In the summer of 2006, the Marines prepared a report on the situation in Anbar, which borders on Syria, from which large numbers of foreign terrorists entered Iraq. The Marines’ report was written at a time when Anbar was the bloodiest province in the country and Ramadi was the most violent city. In one report I will never forget, there were over 1,500 AQI terrorist-related murders in the month of July alone.

Looking back, in late spring of 2006, it was hard to see how this situation could be reversed, especially since requests for additional Marines were denied by the Department of Defense. According to a detailed “lessons learned” analysis by the Marine Corps, top American leaders, including CENTCOM commander General John Abizaid and Multi- National ForceIraq (MNFI) commander General George Casey, had come to believe that the presence of American armed forces was the cause of the uprising. Believing this, the generals ordered the troops to lay off the cities and hunker down in their forward operating bases in preparation to moving out. Generals Abizaid and Casey had essentially thrown their arms up in the air and the intelligence report on Anbar reflected their position. When selected parts of the report were leaked to The Washington Post, the generals described the province as “lost.”

The reality was that despite having the most sophisticated military machine in the history of warfare, we were losing the war in the summer of 2006. We knew it— but some simply could not admit it. The senior leadership began to sense it and I could feel it during many of the briefings I attended, including a major gathering in late summer of 2006 at MNFI HQ. There were so many necessary decisions made that late summer and early fall to change the course of the war that history has already documented and don’t need to be recounted here. But to me, the most important decision came from the White House under President Bush. He realized the war was going badly, that we were losing, and our entire strategy needed to change. The mere fact that he recognized this and proceeded to make the difficult decisions he eventually made is a leadership characteristic our current president lacks.

President Bush not only changed the strategy, but he changed the commander in Iraq, brought in General David Petraeus and, even more important, he brought in Dr. Robert Gates to be the secretary of defense. These two men changed the direction of the war and the situation was reversed within the next two years.

Lt. General (Ret.) Michael T. Flynn spent 33 years as an intelligence officer. Before he was terminated from government service, he served as the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency and the Senior Military Intelligence Officer in the Department of Defense. He has since founded the Flynn Intel Group, a Commercial, Government, and International consulting firm. He lives in Virginia.

Michael Ledeen is the author of War Against the Terror Masters and The Iranian Time Bomb. He spent twenty years at the American Enterprise Institute where he held the Freedom Scholar chair, and now holds a chair at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. He lives in Maryland.