dd

dd

dd

By Andrew F. Smith

Even before the siege of Vicksburg commenced, food was a problem in the city. Confederate soldiers engaged in “the customary pilfering—fruits, vegetables, chickens, and livestock disappeared; troops drained the city of supplies, created shortages, and sent prices soaring. Food became scarce. Butter sold for $1.50 a pound, and flour was virtually unavailable. A substance that passed for coffee was brewed from sun- dried pieces of sweet potato” and families “lived on bacon and cornmeal, and salted mackerel was considered a delicacy.”

Pemberton prohibited food from being shipped out of Mississippi, he encouraged farmers to grow edible crops rather than cotton, and some farmers and plantation owners did just that. Although food was plentiful outside Vicksburg, as the Union army would later prove, plantation owners were often unwilling to sell food to the military authorities, simply because farmers could get better prices on the open market. Well before the arrival of the Federal army, Vicksburg residents had to drive into the countryside to purchase salt for $45 a bag and turkeys at $50 each, which were unavailable in the city. But even when food was available and owners were willing to sell these goods to the military, there was still the problem of how to get the food into Vicksburg. Pemberton had no control over the railroad lines or steamboats, which often carried considerable private cargo rather than military necessities, and there were not enough army wagons or usable roads to carry the needed provisions into the city, or so he would later complain.

Unlike Grant, Pemberton was unwilling to confiscate private foodstuffs and his supply acquisition was limited. In March 1863, General Edward Tracy reported from Vicksburg that in “this garrisoned town, upon which the hopes of a whole people are set, and which is liable at any time to be cut off from its interior lines of communication, there is not now subsistence for one week. The meat ration has already been virtually discontinued, the quality being such that the men utterly refuse to eat it.” When alerted to the need for provisions, commissary agents immediately brought in 500,000 pounds of hog meat, some molasses, corn, salted beef, and salt. Additional provisions were hastily acquired, but they would not be nearly enough.

When the Federal army turned from Jackson and headed west to Vicksburg, Pemberton directed that there should be no provisions left in the area around Vicksburg. The Confederates evacuated Snyder’s Bluff , along with an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 bushels of corn that had to be burned because there were no available transports to move it into the city. The Confederate troops filled what wagons they had with chickens, turkeys, peas, corn, rice, and sugar, and brought them into the city. Beef cattle, dairy cows, sheep, hogs, and mules were rounded up and driven ahead of the retreating Confederate forces. As the Confederate army retreated into Vicksburg on May 17, they brought everything they could into the city. Vicksburg resident Emma Balfour observed: “From 12 o’clock until late in the night the streets and roads were jammed with wagons, cannons, horses, men, mules, stock, sheep, everything you can imagine that appertains to an army— being brought hurriedly within the entrenchment.” She also noted the chaos: “Nothing like order prevailed.”

With what had already been stockpiled in the city, Pemberton believed that Vicksburg “had ample supplies of ammunition as well as of subsistence to stand a siege” for at least six weeks. He believed that before the city starved, Johnston’s army outside the city would lift the siege and free the encircled city, or at least that was his plan. Johnston was shocked that Pemberton allowed his army to be trapped in Vicksburg, and he had no rescue plan for the garrison.

Grant’s forces twice stormed the city’s fortifications, but failed to break through. When additional reinforcements arrived, the Union army settled into trench warfare. While the siege was underway, on May 26, Grant directed Major General Francis Blair to raid the rich agricultural area around the Yazoo River. Verbally, Grant gave “special instructions” to Blair to take or destroy all the food and forage that he found. Blair spent a week going forty- five miles up the river, burning or confiscating crops, cattle, and anything edible. Many of the cattle were herded back to Grant’s army besieging Vicksburg. Northern soldiers secured additional provisions from Southern planters outside the city who, much to the dismay of those sealed up in Vicksburg, readily sold produce and other foodstuff s to the Union army during the siege.

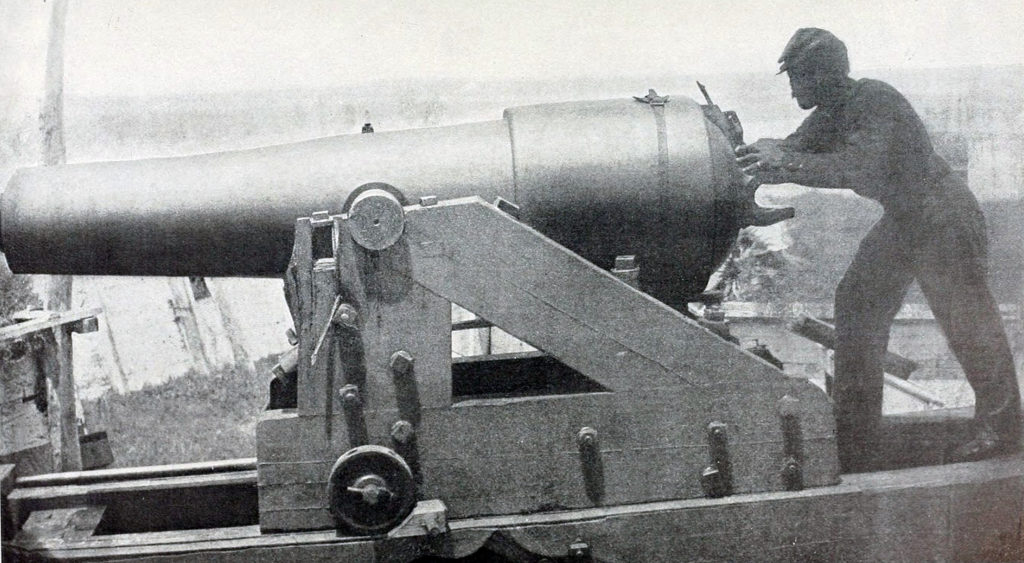

Throughout the siege, artillery and mortars regularly lobbed shells into the city and both soldiers and civilians had a rough time. To protect themselves from the bombardments, civilians dug caves into the hills in the city, cooking outside the entrances to their caves when the shelling was light. Foods commonly eaten in these makeshift shelters included rice and “coffee” brewed from sweet potatoes.

As the siege continued, diminishing food supplies become critical. Daily rations for Confederate soldiers consisted of fourteen ounces of food per man. This included “four ounces each of bacon, flour, or meal, the rest comprising peas, rice, and sugar. It was less than half the rations normally issued and led, some believed, to sharply increased sickness among the debilitated troops.” By May 30, the Confederate meat ration was cut in half. On June 4, Sergeant William Tunnard, of the 3rd Louisiana Infantry, wrote that “all surplus provisions in the city were seized, and rations issued to civilians and soldiers alike. To the perils of the siege began now to be added the prospect of famine.” By June 12, the meat ration was exhausted.

A plentiful supply of cowpeas (also called black- eyed peas), grown by local farmers for animal feed, had been stockpiled in the city before the siege. These were ground into flour that was used to make bread of sorts. Not every Confederate soldier was thankful for this blessing. Ephraim Anderson of the 1st Missouri Brigade wrote that cowpea bread was a “novel species of the hardest of ‘hard tack.’ ” The cowpea meal “was ground at a large mill in the city, and sent to the cooks in camp to be prepared. It was accordingly mixed with cold water and put through the form of baking; but the nature of it was such, that it never got done, and the longer it was cooked, the harder it became on the outside, which was natural, but, at the same time, it grew relatively softer on the inside, and, upon breaking it, you were sure to find raw pea- meal in the centre. The cooks protested that it had been on the fi re two good hours, but it was all to no purpose; yet, on the outside it was so hard, that one might have knocked down a full- grown steer with a chunk of it.” After being fed to the troops for three days and making soldiers sick, cowpea bread was taken off the menu. Boiled cowpeas, however, continued to be about one half of their total subsistence. When the Union soldiers outside the city heard about the cowpea bread, presumably from deserters, a Southerner reported that they “hallooed over for several nights afterwards, enquiring how long the pea- bread would hold out; if it was not about time to lower our colors; and asking us to come over and take a good cup of coffee and eat a biscuit with them. Some of the boys replied that they need not be uneasy about rations, as we had plenty of mules to fall back upon.”

And it did come to mule meat. Alexander St. Clair Abrams, who worked for the Vicksburg Whig, reported that “mules were soon brought in requisition, and their meat sold readily at one dollar per pound, the citizens being as anxious to get it as they were before the investment to purchase the delicacies of the season.” Mule meat “was also distributed among the soldiers, to those who desired it, although it was not given out under the name of rations. A great many of them, however, accepted it in preference to doing without any meat, and the flesh of the mules was equal to the best venison.” Abrams “found the flesh tender and nutritious, and, under the peculiar circumstances, a most desirable description of food.” Ephraim Anderson arrived at one dinner one evening to find that mule meat was the main course: “The appetites of some of the boys were so good, that they partook of it even with a relish.” Anderson himself only tasted it, finding it “not very pleasant and by no means palatable.”The Vicksburg Daily Citizen pronounced mule flesh “very palatable” and “decidedly preferable to the poor beef which has been dealt out to the soldiers for months past, and that a willingness was expressed among those who tried the meat to receive it as regular rations.”

For its part, the Northern press had a field day when reporters heard about Vicksburg’s mules. The Chicago Tribune fabricated a bill of fare for a fictitious “Hôtel de Vicksburg”:

SOUP.

Mule Tail.

BOILED.

Mule Bacon, with poke greens.

Mule Ham, canvassed.

ROAST.

Mule Sirloin.

Mule Bump, stuffed with rice.

VEGETABLES.

Peas and Rice.

ENTREES.

Mule Head, stuffed a la mode.

Mule Ears, fricasseed a la got’ch.

Mule Side, stewed, new style, hair on.

Mule Beef, jerked, a la Mexicana.

Mule Spare Ribs, plain.

Mule Salad.

Mule Tongue, cold, a la Bray.

Mule Liver, hashed.

Mule Brains, a la omelette.

Mule Hoof, soused.

Mule Kidneys, stuffed with peas.

Mule Tripe, fried in pea- meal batter.

JELLIES.

Mule Foot.

PASTRY.

Cottonwood Berry Pies.

Chinaberry Tarts.

DESSERT.

White Oak Acorns.

Blackberry Leaf Tea.

Beech Nuts.

Genuine Confederate Coffee.

LIQUORS.

Mississippi Water, vintage of 1492. Superior, $3

Limestone Water, late importation. Very fi ne, $2.75.

Spring Water, Vicksburg brand, $1.50.

at all hours.

Gentlemen to wait on themselves. Any inattention on the part of servants to be promptly reported at the office.

JEFF. DAVIS & Co., Proprietors.

CARD. The proprietors of the justly celebrated Hôtel de Vicksburg, having enlarged and refitted the same, are now prepared to accommodate all who favor them with a call. Parties arriving by the River or Grant’s inland route, will find Grape, Cannister & Co.’s carriages at the landing, or at any depot on the line of entrenchments. Buck, Ball & Co. take charge of all baggage. No effort will be spared to make the visit of all as interesting as possible.

J. D. & Co.

Mule meat was not all that was consumed in Vicksburg. According to Confederate Major S. H. Lockett, Confederate soldiers ate rats “with the relish of epicures dining on the finest delicacies of the table.” A resident noted in her diary: “rats are hanging dressed in the market for sale with mule meat,— there is nothing else. The officer at the battery told me he had eaten one yesterday.” The price for rats was $2.50.The Daily Citizen reported that they had “not as yet learned of any one experimenting with the flesh of the canine species,” although there were reports of a paucity of dogs and cats on the streets of thecity.

During the last few weeks of June, conditions in Vicksburg worsened. “Many families of wealth had eaten the last mouthful of food in their possession, and the poor class of non- combatants were on the verge of starvation,” according to a report. As soldiers’ rations were reduced, malnutrition set in, and many soldiers ended up in the hospital(or remained ill at their posts), suffering from diseases exacerbated by hunger. Colonel Ashbel Smith of the 2nd Texas Infantry reported:

Our rations were reduced to little more than sufficient to sustain life. Five ounces of musty corn-meal and pea flour were nominally issued daily. In point of fact, this allowance did not exceed three ounces. All the unripe, half brown peaches, the green berries growing on the briars, all were carefully gathered and simmered in a little sugar and water, and used for food. Every eatable vegetable around the works was hunted up for greens. Some two or three men approached to succumb and die from inanition for want of food, but the health of the men did not seem to suff immediately from want of rations, but all gradually emaciated and became weak, and toward the close of the siege many were found with swollen ankles and symptoms of incipient scurvy.

Captain Ferdinand O. Claiborne, of the 3rd Mary land Battery, recorded in his diary: “Our rations are growing more scarce every day and we must eventually come to mule meat. We have a quantity of bacon yet on hand, but breadstuff is the great desideratum. The men receive only one-quarter rations of breadstuff s such as rice, pea meal and rice flour— the corn has given out long since, rations of sugar, lard, molasses and tobacco are issued but this does not make amends for the want of bread, and the men are growing weaker every day.”

On June 28, Pemberton received an anonymous letter signed “many soldiers.” It read, in part: “Our rations have been cut down to one biscuit and a small bit of bacon per day, not enough scarcely to keep soul and body together, much less to stand the hardships we are called upon to stand. If you can’t feed us, you had better surrender us, horrible as the idea is . . . This army is now ripe to mutiny unless it can be fed.” Deserters reported the same thing. Charles A. Dana wrote on June 29,to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton: “Two separate parties of deserters from Vicksburg agree in the statement that the provisions of the place are near the point of total exhaustion; that rations have now been reduced lower than ever; that extreme dissatisfaction exists among the garrison, and that it is agreed on all hands that the city will be surrendered on Saturday, July 4, if, indeed, it can hold on so long as that.”

The Father of Waters Goes Unvexed to the Sea

The deserters were right. General Pemberton, along with more than 27,000 Confederate soldiers, surrendered on the Fourth of July. The Confederates had received no rations on July 3, and the victorious Union soldiers empathized with them. Since the Federal army had ample supplies, many soldiers gave Confederate soldiers bread and other food, which “was accepted with avidity and thanks.” A Federal soldier named Isaac Jackson found that the Confederate soldiers “were nearly starved. I was talking with one who had been eating mule meat for four days & but one biscuit a day for over a week. It looked hard to see the poor fellow pitch into our ‘hard tack’ which our boys gave them. We had plenty, and they carried them off by armloads. Poor fellows, they needed them.” According to a Confederate soldier, Union soldiers “aided us greatly by many acts of kindness. They would go out to their sutler’s tent with the greenbacks we had borrowed from their dead comrades and purchase food for us, and doubtless many a starving ‘Reb’ felt that his life was thussaved.”

A Confederate officer named J. H. Jones approached a Union lieutenant and requested permission to buy food. The lieutenant responded that he needed to ask permission through military channels for that to happen. Jones replied that he must know, from my appearance, I would be dead some days before its return, to which he laughingly assented. He suddenly remembered that he had some “trash” in his haversack and offered it. The “trash” consisted of about two pounds of gingersnaps and butter crackers; luxuries I had not seen for three years. I was struck dumb with amazement. “Trash,” quoth he? . . . I fell upon that “trash” like a hungry wolf and devoured it. A bystander afterwards declared that it disappeared in my mouth like grains of rice before a Chinaman’s chop stick. Be that as it may, the memory of that sumptuous feast still lingers, and my heart yet warms with gratitude towards that good officer for the blessing he bestowed.”

Vicksburg merchants who had hoarded supplies during the siege began selling food to civilians at extortionate prices: “$200 for a barrel of flour, $30 for the same amount of sugar, corn $100 a bushel and $5 for a pound of flour.” Other merchants brought out “wines for which the sick had pined in vain” and “luxuries of various kinds were founding profusion.” A great deal of food collected by the Confederate government was also in Vicksburg. When located, it was “rolled out into the streets” and given to the Confederate soldiers and the civilians of the city. William H. Tunnard of the 3rd Louisiana reported that the Union troops threw the provisions into the streets and shouted, “ ‘Here rebs, help yourselves, you are naked and starving and need them.’ ” Tunnard observed, “What a strange spectacle of war between those who were recently deadly foes.”

Within a few days, the Confederate soldiers were paroled— sent home to await official exchange. As for wounded and ill soldiers, they remained in Vicksburg, while medical professionals tried to cure their illnesses and treat their wounds. Weeks after the surrender, many still had not recovered. A Northern reporter described them in this way: “Their emaciated appearance made them look like a weak, tottering procession of skeletons, while their dirty white uniforms assisted materially in adding to the ghastliness of the pallor that overspread eachcountenance.”

Nine days after Vicksburg fell, Grant sent Sherman back to Jackson, Mississippi, which Johnston had reoccupied. Sherman was ordered to break up Johnston’s army and “destroy the rolling stock and everything valuable for carrying on war, or placing it beyond the reach of the rebel enemy.” Sherman reported back to Grant: “We are absolutely stripping the country of corn, cattle, hogs, sheep, poultry, everything, and the new- growing corn is being thrown open as pasture fields or hauled for the use of our animals.” Sherman considered this “wholesale destruction” to be the scourge of war. As a reporter for the Chicago Times wrote: “The country between Vicksburg and Jackson was completely devastated. No subsistence of any kind remained. Every growing crop had been destroyed when possible. Wheat was burned in the barn and stack whenever found. Provisions of every kind were brought away or destroyed. Livestock was slaughtered for use, or driven back on foot.”

As for Pemberton, Grant released him and sent him to report back to Johnston. Pemberton was roundly criticized in Southern newspapers for placing the garrison in the position of being starved out. On August3, 1863, he wrote his official report of the surrender. In it, he claimed that the lack of food played no part in his decision to surrender the city: “The assertion that the surrender of Vicksburg was compelled by the want of subsistence, or that the garrison was starved out, is one entirely destitute of truth. There was at no time any absolute suffering for want of food among the garrison. That the men were put upon greatly reduced rations is undeniably true; but, in the opinion of many medical officers, it is at least questionable whether under all the circumstances this was at all injurious to their health.”

To support his assertion, Pemberton defiantly pointed out that, at the time of surrender, Vicksburg had “about 40,000 pounds of pork and bacon, which had been reserved for the subsistence of my troops in the event of attempting to cut my way out of the city; also, 51,241pounds of rice, 5,000 bushels of peas, 92,234 pounds of sugar, 3,240pounds of soap, 527 pounds of tallow candles, 27 pounds of Star candles, and 428,000 pounds of salt.” This looks impressive, but is not. Soap, candles, and salt are not edible, and the quality of the meat and rice was highly questionable, and even if it had been distributed, would have run out in a few days. That just left a large sugar reserve, which is hardly sustenance.

The availability of food was contradicted by virtually every other report— Confederate and Federal— that emerged from Vicksburg. Confederate soldiers and civilians might have been able to hold out for a few more days, but without food the city and its garrison would have starved. According to all accounts, Confederate soldiers had no food. According to the surrender accord, Grant was required to supply the Confederate army with food. Most likely such statements were Pemberton’s way of avoiding responsibility for his failure to store enough food in the city for a long siege or, possibly, for his failure to avoid entrapment in Vicksburg in the first place, a view that Johnston maintained at the time. Pemberton’s assertion that there were insufficient means of transportation to move food into the city is also questionable, as Grant proved when he landed at Bruinsberg and confiscated all the transport vehicles he needed from surrounding plantations.

When it was suggested to Jefferson Davis that Vicksburg fell for want of provisions, he responded, “Yes, from want of provisions inside and a general outside who wouldn’t fight.” Davis’s swipe at Johnston’s failure to relieve Vicksburg may have been unjustified. His forces were located east of Jackson, and they were also without provisions, which was one reason Johnston gave for his failure to come to the aid of Vicksburg. Independent observers reported that his army “had been subsisting almost wholly on green corn for several weeks, and half his troops were probably unfit for duty. They were found sick at almost every house, and languishing or dead in hundreds of fence- corners. The utter impossibility of supplying his army with necessary food had been a sufficient reason for Johnston’s not falling upon Grant’s rear and attempting to raise the siege.”

The final conquest of the Mississippi River occurred five days after the fall of Vicksburg, when Port Hudson in Louisiana fell to the besieging army directed by Nathaniel Banks. Like Grant at Vicksburg, Banks tried to assault the Confederate fortifications at Port Hudson, and when direct assault failed, he settled down into a long siege. Port Hudson was also under the nominal command of Pemberton, who had been responsible for supplying the town with enough food to survive a siege. For the next forty-eight days, Banks tried to starve out the Confederate garrison. Like the Confederate forces in Vicksburg, the defenders of Port Hudson suffered from malnutrition and then starvation. One Confederate soldier reported in his diary that he and fellow soldiers had eaten “all the beef— all the mules— all the dogs— and all the rats.” After news of Vicksburg’s fall reached the garrison and their food and supplies were exhausted, the Confederates surrendered Port Hudson on July 9. For the first time in two years, the Mississippi River was open for ships to travel unimpeded from the Midwest to the mouth of the river. In Abraham Lincoln’s immortal phrase, “The Father of Waters goes unvexed to the sea.”

In late November 1863, General Grant, flush from his victory at Vicksburg, took charge of the stalled and starving Federal army at Chattanooga, where he defeated the Confederates. Grant’s victories at Vicksburg and Chattanooga made him a national hero in the North.

Vicksburg Effects

During the Mississippi River campaign, food was used as both a strategic and tactical weapon. As a tactical weapon, the sieges prevented food from entering the cities, which directly contributed to their surrender. Strategically, the victories at Vicksburg and Port Hudson prevented food and supplies from Texas from reaching the Southern states. As a result of the loss of beef from Texas, the South had to reduce its meat rations for Confederate soldiers east of the Mississippi River.44 Just as important was the strategic value of the Mississippi River for Northern commerce. After these Union victories, Midwestern farmers could once again send provisions down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. Southern farmers and plantation owners with access to the Mississippi began selling molasses, cotton, and other commodities to Union traders, and this sapped Confederate morale.

Most important, the Vicksburg campaign represented a sea change in the Federal strategy to end the war. At the beginning of the war, Northerners believed that there was strong support for the Union in the South, and that Southerners would eventually come to their senses, reject the fi rebrand secessionists, and rejoin the Union willingly. However, after occupying large sections of the Confederacy in Arkansas, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Virginia, it became clear that Northern forces were viewed as conquerors and not as liberators, and that whatever support existed for the Union in the South before the war had largely vanished once the conflict began. The activities of Southern guerrillas and cavalry raids proved that it would be impossible to supply the Federal troops who would have to garrison the South, which led Grant, Sherman, Lincoln, and many other Northern leaders to conclude that it would be impossible to win the war by traditional military means. What emerged was a new strategy that focused on the use of raiding armies to disrupt the Southern food supply, making it harder for Confederate guerrillas and armies to operate. As this new policy would directly affect civilians, it would also sap the South’s morale and its willingness to continue the war, or so it was hoped.

Excerpted from Starving the South by Andrew F. Smith. Copyright 2011 by Andrew F. Smith. All rights reserved.

ANDREW F. SMITH is the author of Starving the South, a faculty member at the New School and editor-in-chief of The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. He lives in New York.