By Tim Newark

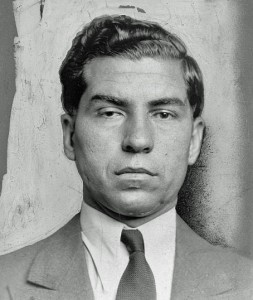

Locked in prison, reading daily newspaper reports of Allied victories, Charlie Luciano got impatient. He wanted to be part of the action. If the U.S. government were grateful to him for his help against enemy agents at home, then they’d be knocked out if he got his hands really dirty and stepped forward for active duty. According to Meyer Lansky, he had it all worked out. He would volunteer to act as a scout or liaison officer for frontline troops. He’d put his neck on the line by being parachuted into action—behind enemy lines—and use his considerable influence to win the war for America. Lansky laughed, picturing him landing on top of a church spire. But Luciano couldn’t see the funny side—he was deadly serious.

By January 1943, the Allies were on the offensive in the Mediterranean. They had held and defeated the Germans and Italians in North Africa and were now looking to open up a second European front to put more pressure on Hitler, while the German army was fighting for its life against the Soviet Union in Russia. The final decision was made at the Casablanca Conference between U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston Churchill. After much debate, the Americans agreed to support Churchill in his desire to invade Mussolini’s Italy—the soft underbelly of Nazi Europe. To do this, they would first have to attack Sicily in an operation that would go by the code name “Husky.”

Having determined the location of the next Allied thrust, Churchill then had to admit that the Americans possessed an undeniable advantage when it came to dealing with Italians. “In view of the friendly feeling towards America entertained by a great number of citizens of Italy,” said Roosevelt in a telegram to Churchill, “and in consideration of the large number of citizens of the United States who are of Italian descent, it is my opinion that our military problem will be made less difficult by giving to the Allied Military Government [in Sicily] as much of an American character as is practicable.”

Churchill agreed, but in secret correspondence, his ambassador to Washington, D.C., expressed the fear that Italian-American anti-Fascist agents appointed to Sicily might well turn out to have Mafia links.

“Italian communities in New York were already beginning to lay down the law about administration of Italy,” wrote the British ambassador. “Italian communities here had an intimate knowledge and connexion with Huskyland [Sicily] and quite unimportant appointments might have reactions here (for instance it would be known at once if one of our ‘anti- Fascist’ appointees was a Mafia man as was not unlikely).”

He would not be far wrong. That intimate connection between New York and Sicily could well be a two-edged sword for the Allies.

Having determined the next phase of the war, preparations began for an invasion of Sicily. East Coast Naval Intelligence officers saw an opportunity here to exploit further their connections with Sicilian gangsters. This time, rather than the criminal links confined to the files of his New York office, Haffenden was encouraged to report his contacts to the Washington headquarters of Captain Wallace S. Wharton, head of the Counter-Intelligence Section, Office of Naval Intelligence.

“On the occasions when Commander Haffenden gave names to me,” said Wharton, “he told me that he had obtained these names from his contacts in the underworld. The names of the individuals in Sicily who could be trusted turned out to be 40 percent correct, upon eventual checkup and on the basis of actual experience.”

Luciano’s wild proposal of putting himself in the frontline proved to be true. Lansky told Haffenden about Luciano’s suggestion and the commander passed it on to Captain Wharton in Washington. “Haffenden told me that Luciano was willing to go to Sicily,” recalled the head of Counter Intelligence, “and contact natives there, in the event of an invasion by our armed forces, and to win these natives over to support the United States war effort, particularly during the amphibious phase of an invasion.”

Haffenden argued the case for Luciano, saying he could persuade Governor Dewey to give him a pardon and send him to Sicily via a neutral country, such as Portugal. Full of enthusiasm for the idea, he said that Luciano recommended that U.S. forces land in the Golfo di Castellammare—a favorite Mafia drug- smuggling haunt near Palermo and home to many of those mobsters caught up in the gang war of the late 1920s. Wharton seriously considered the fantastic suggestion of sending the U.S. head of organized crime to a theater of war but could see this might well become a scandal after the war and reprimanded Haffenden for a lack of political judgment. He was more than happy just getting information from these gangsters without actually sending them to fight with tommy guns on the beaches of their homeland.

Lieutenant Anthony J. Marsloe had no qualms about dealing with gangsters. “The exploitation of informants, irrespective of their backgrounds, is not only desirous,” he said, “but necessary when the nation is struggling for its existence.”

He was a law graduate and had served under Captain MacFall and Haffenden since the beginning of the project. Two other members of his four-man team were a practicing attorney and an investigator who would later be tasked with exposing waterfront racketeering. They were now told to speak to all kinds of shady characters in order to get data of use in a projected invasion.

“Because of my personal knowledge of Sicily and the dialects of Sicily,” recalled Marsloe, “various personalities, otherwise unidentified, were sent to me by Commander Haffenden. These men were interviewed and photographs, documents or other matters of interest were taken, and in turn given to Commander Haffenden.”

Meyer Lansky was actively involved in bringing some of these personalities to Haffenden’s office. The naval officers wanted everything they knew about the shape of the coastline and major landing points. “The Navy wanted from the Italians all the pictures they could possibly get of every port of Sicily, of every channel,” said Lansky, “and also to get men that were in Italy more recently and had knowledge of water and coastlines—to bring them to the Navy so they could talk to them.” Haffenden would then pull out big maps and “he showed them the maps for them to recognize their villages and to compare the maps with their knowledge of their villages.”

From his jail cell, Luciano recommended certain people who knew Sicily well, and Lansky escorted them to the Naval Intelligence offices. Socks Lanza helped out, too. “Sometimes some of the Sicilians were very nervous,” said Lanza. “Joe [Adonis] would just mention the name of Lucky Luciano and say he had given them orders to talk. If the Sicilians were still reluctant, Joe would stop smiling and say, ‘Lucky will not be pleased to hear that you have not been helpful.’ ”

All the information was sifted and analyzed with much of it ending up on a huge wall map in Haffenden’s office with code numbers referring to particular reports from specific individuals. Some of these were major underworld figures who were part of the international network of drug smugglers established by Luciano before he went to jail. Vincent Mangano ran an import-export business between the United States and Italy before the war, which was a cover for his role as key broker between the American and Sicilian Mafias.

That Frank Costello was also involved in this gathering of material was suggested by the testimony of federal narcotics agent George White. He told the Kefauver Senate Committee inquiry into organized crime in 1950 that veteran drug smuggler August Del Grazio had approached him with a deal coming from Frank Costello on behalf of Luciano.

“The proffered deal,” recalled Senator Estes Kefauver, “was that Luciano would use his Mafia position to arrange contacts for undercover American agents and that therefore Sicily would be a much softer target than it might otherwise be.” Luciano’s asking price for all this was freedom from jail and his own travel to Sicily to make the arrangements.

Lansky denied the involvement of August Del Grazio in the war time dealings. “I never knew of George White and I still don’t know of August Del Grazio,” said Lansky in 1954. Was he shielding some secret connection? It is interesting to note that Del Grazio, also known as “Little Augie the Wop,” was the drug smuggler trusted by Luciano to consolidate his narcotics shipments in Weimar Germany in 1931.

As the days counted down to Operation Husky—the Allied invasion of Sicily in the summer of 1943—it was not only U.S. Naval Intelligence that woke up to the advantages of having homegrown links with the Sicilian Mafia. Planners for the U.S.

Joint Chiefs of Staff—those senior military commanders in Washington—came up with a daring line of action not dissimilar to Lucky Luciano’s own suggestion. In their Special Military Plan for Psychological Warfare in Sicily, dated April 9, 1943, they suggested infiltrating Sicilian-Americans onto the island so they could link up with dissident organizations and foment revolt against the Fascist authorities.

This included the “Establishment of contact and communications with the leaders of separatist nuclei, disaffected workers, and clandestine radical groups, e.g., the Mafia, and giving them every possible aid,” stated the joint staff planners’ report.

It would not prove too difficult, as Mussolini had come down hard on the Mafia in the 1920s when he sent to Sicily the tough law enforcer Cesare Mori to subdue and humiliate Mafiosi and their families. Many had been tortured, sent to jail, or fled abroad to America. It was this hunger for revenge against the Blackshirts that the American military wanted to utilize.

The United States would supply them with weapons and explosives so they could blow up Axis military installations and strategically important bridges and railroads. This extraordinary concept of arming lawbreakers so they could fight against Fascists and Nazis was approved by the very highest military authorities—including General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commanding general of the North African Theater of Operations.

The Americans were not alone in their wish to make contact with the Mafia in Sicily. Their military partners, the British, had their own plans to connect with the Sicilian underworld. The British Secret Intelligence Ser vice produced a Handbook on Politics and Intelligence Ser vices for Sicily. In it they identified a figure called Vito La Mantia as head of a Mafia group. They described him as “very anti-Fascist and, if still alive, might supply valuable information: uneducated but influential: was last reported as the manager of a property belonging to the Mafia in Via Notabartolo, Palermo.” It was not a very impressive contact and does not tally with any known Mafia figure quoted in American circles, but it does reveal that it was not exclusively the Americans or their Naval Intelligence that considered utilizing the Mafia in the conquest of Sicily.

On the night of July 9, 1943, American and British landing craft crashed through the waves of the Mediterranean to land on beaches along the southeast corner of Sicily. Ahead of them exploded a curtain of Allied shells and bombs, smashing against Axis pillboxes, crushing any resistance to the landing. Once ashore, troops scrambled across the sand as tanks and trucks were unloaded, building up their strength for the next phase of the invasion. The British were to advance north along the eastern coast of the island from Siracusa to Messina. All the way they would encounter stiff resistance from German soldiers determined to slow their advance, so they could evacuate as many of their own troops across the sea to mainland Italy. The British advance would be measured in blood.

In contrast, the Americans quickly cut across Sicily to occupy the western half of the island and take its capital, Palermo, on the northwest coast. Their casualties were a fraction of those suffered by the British. Had Roosevelt and Eisenhower been right? Had they secretly deployed their Italian- American contacts to somehow ease the progress of their own soldiers? Had underworld links across the ocean instructed the Mafia in Sicily to aid the Americans and discourage Axis troops from attacking them? It has been a long- held belief that that is exactly what happened.

Despite his wishes, Lucky Luciano was not among the seasick Americans staggering out of their landing craft, but Lieutenant Marsloe was. He had swapped his desk job in New York for active service, along with three other Naval Intelligence colleagues, and their mission was to make the most of the information given to them by Luciano’s contacts. They were broken up into two teams and Marsloe landed at Gela. The data gathered in New York was of “tremendous help following the landing,” said Marsloe, “because we gained an insight into the customs and mores of these people . . . the manner in which the ports were operated, the chains of command together with their material culture.”

For Marsloe’s colleague, Lieutenant Paul Alfieri, there were more direct benefits. “One of the most important plans was to contact persons who had been deported for any crime from the United States to their homeland in Sicily,” said Alfieri, “and one of my first successes after landing at Licata was in connection with this.”

This connection began back on the Lower East Side, when a sixteen-year-old kid shot a policeman and was destined for the electric chair. His mother was a cousin of Lucky Luciano and begged him to help her boy escape justice. The mobster intervened and had him smuggled out of the country via Canada to Sicily. There, with his America connections, he became head of his local Mafia family. It was this criminal that Alfieri made contact with in Licata, and the code word he was to give him was “Lucky Luciano.”

“Maybe that sounds crazy right in the middle of the war,” said Lansky, “but one of those agents told me later that those words were magic. People smiled and after that everything was easy.” Even if Luciano wasn’t there, his reputation was opening doors.

The young renegade mafioso led Alfieri to the local headquarters of the Italian navy. With the assistance of his armed henchmen, they killed the German guards outside and broke in. They blew open a safe and inside Alfieri found documents describing German and Italian defenses for the island as well as a valuable radio codebook. Secret maps revealed the locations of minefields and the safe routes through them, thus saving many American lives. It was a tremendous breakthrough for which Alfieri was awarded the Legion of Merit—his actions “contributing in large mea sure to the success of our invasion forces,” said the presidential citation. It was a medal that Luciano might well have felt he deserved, too.

But Marsloe, Alfieri, and their colleagues were only four intelligence agents compared to the hundreds of others serving with the army. Their impact on the campaign in Sicily began and ended on the coast. From then on, it was up to the military officers of the Counterintelligence Corps (CIC) to assist the advance of their frontline soldiers into the heart of Sicily, and they did not have the benefit of Luciano’s briefings.

Or did they? There is a notorious story that is often quoted as proof that Lucky Luciano’s long shadow hung over the fighting in Sicily.

Five days after the Allied landing, on July 14, 1943, an American fighter plane flew low over the small town of Villalba in central Sicily. As its wings nearly brushed the terracotta roofs of the buildings, native Sicilians could see a yellow banner fluttering from the side of the cockpit. They swore it bore a large black “L” in the middle of the flag. As the aircraft swooped over a grand farm house on the outskirts of the town, the pilot tossed out a bag that crashed into the dust nearby. A servant from the farm house hurriedly retrieved it and showed it to his master.

The owner of the farm house was Don Calogero Vizzini. A little man in his sixties with a potbelly, he dressed in the usual understated style of a local businessman with his shirtsleeves rolled up and braces hauling his trousers up over his stomach.

The image belied his true importance. Don Calo was, in fact, the leading mafioso of the region, and he would later become a major player in postwar Sicily, when he would have direct links with Luciano.

As Don Calo opened the bag dropped by the pilot, he saw at once that an important message had been sent to him by his friend in New York. Inside was a yellow silk handkerchief bearing the “L” of Lucky Luciano. It was a traditional Mafia greeting, and Don Calo knew exactly what he must do next. He wrote a coded message to another mafioso, Giuseppe Genco Russo, and instructed him to give every possible assistance to the advancing Americans. Six days after that, on the twentieth, according to the legend, three U.S. tanks rumbled into the town center of Villalba. Children danced around the vehicles, hoping for sweets and chewing gum. A little yellow pennant flew from the radio aerial of one of the tanks—on it a black “L.” An American officer emerged out of the tank and, speaking in the local Sicilian dialect, asked to see Don Calo. The crowd parted as the Mafioso made his way toward the tank. He handed his yellow flag with a black “L” to the American, who helped him climb up onto the hull and then disappeared with him into the turret.

The following day, the twenty-first, the Americans braced themselves for an assault against a mountain pass at Monte Cammarata, to the north of Villalba, held by Italian troops reinforced by Germans armed with eighty-eight-millimeter antitank guns and Tiger tanks. But during the night, Don Calo and Russo had worked their magic and their agents had quietly stolen into the Axis camp. By the next morning, the Italian troops had taken the persuasive advice of the Mafia henchmen, dumped their uniforms and weapons, and disappeared into the hills.

The few Germans left behind were hopelessly outnumbered and promptly withdrew their forces. Surely there could be no better example of how Luciano and his Sicilian Mafia contacts were helping the Americans win the war in Sicily. It would be— if it were true.

The Villalba tale was first told in 1962 by Michele Pantaleone, a journalist whose family had lived in the town for years. His account was then taken up by the British travel writer Norman Lewis, who repeated it for an English-language audience in his much admired book about the Mafia, The Honoured Society. The only problem with this is that Pantaleone was a very biased source. He was a brave campaigner against the Mafia in his country, but he was also a Communist supporter who was in direct competition with the political power wielded by Don Calo. Added to this was a long-running dispute between the Pantaleone family and the Vizzinis over who owned the rights to a local property. As a result, American OSS agents based in Sicily considered him an unreliable witness.

None of this would matter if only there were other records that corroborated Pantaleone’s story. But the daily field reports kept by the U.S. Army as it pushed on through Sicily, reveal a very different picture of the events around Villalba in July 1943. Documents kept at the U.S. Army Military History Institute record that it was a mechanized unit— the Forty- fifth Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop— that entered Villalba on the twentieth. All they found, according to their daily journal, were two small Italian tanks that had been wrecked and abandoned by the retreating Axis forces. Nothing was mentioned of a major body of Axis troops located at Monte Cammarata. Indeed, other U.S. troops were already fifty miles north of Villalba on their way to Palermo and reporting minimum resistance, if any at all. The Third Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop was also operating in the area and their daily journal for the twentieth and twenty- first reports that the road from Cammarata to Santo Stefano was clear. Any minor resistance was quickly overcome as U.S. troops plowed on toward Corleone. None of this verifies the story told by Pantaleone.

A final piece of evidence is provided in the memoirs of Luigi Lumia, a one time mayor of Villalba. His source was a young man who accompanied Don Calo into the American tank, acting as interpreter for the Mafia boss. According to the interpreter, Don Calo was taken away to be questioned about an incident a few days earlier when an American jeep had come under fire and one of the soldiers was killed. The shots had come from a clump of olive trees near a farm. The Americans shot back and this ignited a field of dry crops. Don Calo nodded sagely, knowing exactly what had happened. The fire had spread, he explained, and set off some boxes of ammunition left by the retreating Italians. It sounded like heavy gunfire, but really it was nothing—the Americans faced no local resistance at all. The explanation sounded farfetched to the American interrogator and he lost his patience with the old man. He began shouting at Don Calo, telling him to get out and walk back to his town. This was an enormous loss of face for the mafioso and he was profoundly embarrassed by the whole affair.

“It was already nighttime,” recalled Lumia, “and Calogero Vizzini, tired and browbeaten, was driven back to his house, halfway between the Americans and the countryside. He told his interpreter not to tell anybody what had happened and then lay down in his bed and went to sleep.”

Don Calo would have far preferred the tale told by his enemy— Pantaleone—to be spread around, as that made him look more important than the reality of this humiliating clash revealed. Maybe that is why the Villalba legend has endured for so long. It presents Don Calo and Lucky Luciano as far more integral to the American victory in Sicily than they really were.

In truth, it is clear that the American advance in central and western Sicily was too overwhelming and swift for there to be any opportunity or need for the Mafia to come to their assistance. The only direct proof we have of Luciano’s influence is on the coast during the initial landing phase with the testimony of the four naval intelligence agents. Beyond that, the mobster’s influence was not needed and not called on. That is the truth of what happened in Sicily in 1943. Lucky Luciano might have been itching to get into the combat zone, but there was no need for him.

Despite the truth that Luciano had little impact on the Sicilian campaign, he got his reward for his general war time assistance from the U.S. government in early January 1946. After spending nine years, nine months in jail, his nemesis Governor Thomas E. Dewey commuted his sentence.

Far from hiding the nature of Luciano’s ser vice to the nation, Dewey made a statement to the legislature in which he said, “Upon the entry of the United States into the war, Luciano’s aid was sought by the armed ser vices in inducing others to provide information concerning possible enemy attack. It appears that he cooperated in such effort though the actual value of the information procured is not clear.”

A month later, New York Times journalist Meyer Berger speculated further on what this aid might be. He claimed that Luciano had been pardoned “ostensibly for help he gave the Office of Strategic Ser vices before the Army’s Italy invasion. It is understood that Luciano provided Army Intelligence with the names of Sicilian and Neapolitan Camorra members, and a list of Italians sent back to their native country after criminal conviction in the United States.”

The reporter appears to have got his facts wrong, as we know it was U.S. Naval Intelligence that communicated with Luciano in jail, not the OSS. But the reference to the precursor of the CIA is intriguing due to future references to Luciano perhaps playing a role in the Cold War. Certainly, OSS agents were very active in Palermo and had close links with major Mafia figures in Sicily.

Luciano might have been free, but he was no longer welcome in America. In preparation for deportation to Italy, he was moved to a cell on Ellis Island, the entry point to the United States for his family and so many other immigrants thirty-nine years before. Meyer Lansky, Frank Costello, and Moses Polakoff visited him there for their final instructions from him. To comply with government rules that only $60 could be taken out of the country, Luciano gave up the $400 in cash he had on him to Costello. With no limitation on the use of travelers’ checks, Costello gave Luciano $2,500 in unsigned checks and explained to Luciano how to sign for them. Three unnamed relatives visited him on Ellis Island, perhaps his brothers and sister.

On February 9, Luciano was escorted by two agents of the U.S. immigration service onto the seven-thousand-ton freighter Laura Keene, which was shipping a consignment of flour. Reporters swarmed around the dockside, wanting a final picture of the king of the underworld. Fifteen journalists were refused admittance to the pier by a menacing guard of longshoremen armed with baling hooks. They’d been provided by the Mafia to keep the media at bay and their boss told the reporters to “beat it.”

Six police guards working in pairs watched Luciano twenty-four hours a day in eight- hour shifts during his period of custody on board the Laura Keene. Officially, they denied the presence of any liquor or extra food on board for Luciano, but Lansky told a different story.

On the evening before Luciano’s departure, all the city’s top mobsters gathered on board the freighter for a farewell party. They included Meyer Lansky, Frank Costello, Albert Anastasia, Bugsy Siegel, William Moretti, Tommy Lucchese, Joe Adonis, and Stefano Magaddino. Someone must have bribed the police guards generously. Champagne corks popped and they laughed about old times. “We had a wonderful meal aboard,” said Lansky, “all kinds of seafood fresh from the Fulton Fish Market, and spaghetti and wine and a lots [sic] of kosher delicacies.” Luciano loved his Jewish food.

“Lucky also wanted us to bring some girls to take along with him on the ship to keep him company. I asked Adonis to do something about that . . . Joe found three showgirls from the Copacabana Club and there was no difficulty in getting them aboard. The authorities cooperated even on that. Nobody going into exile ever had a better [s]end- off.”

An FBI report gives yet another version of Luciano’s last days in America. An anonymous FBI agent visited him on board the Laura Keene.

“I had no trouble whatsoever with the stevedores on the pier or on board the ship,” he reported, “nor was I molested or threatened.” The stevedores, “chiefly Italians, looked upon Luciano as more or less a hero, and that any word from him requesting that the reporters be barred was all that was needed to have it carried out by the stevedores as an order . . . there would have been bloodshed if the reporters tried to storm the pier in an unauthorized entry.”

The agent flashed his ID to the steamship guard and was shown to Luciano’s cabin.

“When I entered Mr. Luciano’s cabin, I told him that I was stopped by the representatives of the press at the end of the pier and that they would like to interview him. He reacted unfavorably to the idea and he told me that since the press had not been too nice to him in the past, he had no desire to give any statements. “Mr. Luciano was quartered in a cabin known as the ‘gun crew quarters’ aft of amidship. In the cabin with Mr. Luciano was the first mate who informed Luciano that he would have to remain in the quarters assigned to him, until the ‘old man,’ meaning the captain, orders the change of quarters.”

The FBI agent contradicts Lansky’s story of a farewell feast. On Saturday evening, February 9, he was told by guards that Luciano had baked macaroni and steak for dinner. He asked for a cup of tea but was told there was none and he settled for a drink of milk. They stated there was “no evidence of any parties, drinking or visitors to Luciano during the time he was under their surveillance” from midnight to 8:00 a.m. on Saturday the ninth through Sunday the tenth. They denied he had been visited by Albert Anastasia.

The agent returned on Luciano’s last day in Brooklyn docks at the Bush Terminal at 6:00 a.m. “Upon my arrival there, I saw a gang or mob of 60 to 80 men and about 20 to 30 cars. I have no idea to their identity or their purpose for being on hand.”

When the ship left the pier at 8:50 a.m., a launch followed them for three miles. The agent guessed it was members of the press trying to get one final shot of Luciano. The agent left the ship at 2:00 p.m. when he caught a ride on a fishing ship returning to the Brooklyn docks.

The FBI were generally cynical about the deal with U.S. Naval Intelligence, and J. Edgar Hoover’s suspicions were confirmed when on March 1, 1946, he received a letter from FBI Special Agent E. E. Conroy stating that “Haffenden admitted he was friendly with Costello and had played golf with him” at the Pomonok Country Club in Flushing. To this was added the allegation that “there has been talk around the city that $250,000 would be paid for the release of Luciano from State Prison. This money, however, would probably not go to Haffenden, but rather to others in political circles. It is observed that Haffenden has already been rewarded with the position of Commissioner of Marine and Aviation.” This key position gave Haffenden jurisdiction over the docks of the city of New York as well as LaGuardia and Idlewild airports. “When the latter airport is completed there will be a tremendous number of concessions to be leased and the possibilities of graft are said to be great.”

A letter dated March 6 from FBI Assistant Director A. Rosen said the newspaper stories about Luciano’s assistance to navy and army authorities “might be laid to a fraudulent affidavit on the part of Commander Charles Radcliffe Haffenden.” In the same letter, Rosen said that despite Haffenden receiving a Purple Heart for wounds in combat, Special Agent Conroy said that Haffenden had received no such wounds and was “hospitalized as a result of a large gun going off near him thus renewing a stomach ailment.”

In a later FBI report of March 13, it was alleged that Frank Costello had Haffenden appointed to his new role, “as it is generally felt that Frank Costello has considerable control in the present city administration.” It was said that Haffenden, after returning from Iwo Jima, where he had been wounded, was visited in the hospital by “his good friend” Moses Polakoff and “that Polakoff had induced him, Haffenden, to write a letter to Charles Breitel, Counsel to the Governor of the State of New York. Haffenden explained to the informant that he was not feeling very well and he wanted to do a good turn and he did not see anything wrong about writing the letter on Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano.”

As the FBI investigation delved deeper, U.S. Naval Intelligence sought to distance itself from the affair by claiming that its files failed to indicate that Luciano had ever furnished assistance or information to them. On April 17, 1946, Hoover expressed a personal interest to Rosen in wanting to know the details behind Luciano’s parole. As Rosen explored further, he dispatched a memorandum on April 18, 1946, saying that he had spoken to a key witness for the prosecution in the Luciano trial who admitted that “he had perjured himself when he testified against Lucky Luciano” and “states that considerable opinion exists to the effect that Luciano was not guilty of the charges for which he was convicted and that Governor Dewey’s parole of Luciano was motivated partially as an easing of Dewey’s conscience.” He then added in his own handwriting—“so sorry.”

On May 17, Rosen reported that he had received a letter from the office of the chief of naval operations acknowledging that “Luciano was employed as an informant” but “the nature and extent of his assistance is not reflected in Navy records, and further that Haffenden was censured officially for his actions.”

Hoover’s comment on the whole affair was noted in a memorandum of June 6, 1946, to Rosen: “A shocking example of misuse of Navy authority in interest of a hoodlum. It surprises me they didn’t give Luciano the Navy Cross.”

Rosen was later informed that Haffenden had paid the price for their investigation, when he was forced to resign as commissioner of the city’s Department of Marine and Aviation by Mayor William O’Dwyer in May 1946. The excuse for this was that the mayor had not been satisfied with Haffenden’s administration of the position following an item appearing in a New York newspaper. “Unless advised to the contrary by the Bureau, no further action is contemplated by the New York Division in this matter,” concluded the FBI.

For the moment that was the end of the FBI’s involvement in Luciano’s affairs, but Hoover was itching to match Dewey by nailing the mobster. That opportunity would come a year later. Former New York mayor La Guardia— he had finished his third term in 1945— was less than generous when he heard of Luciano’s departure. “I’m sorry Italy is getting this bum back,” he told a radio audience and added that he was shocked that Frank Costello should be allowed to visit him on Ellis Island. “What is the limit of Costello’s power in the city?” he asked, indicating that that mobster was now the real head of the American Mafia.

The terms and conditions of Luciano’s deportation were very clear—if he ever reentered the United States he would be deemed an escaped convict and would be required to serve out the maximum of his original prison sentence. He could never again set foot on American territory. For the forty- eight- year- old Luciano, it might have marked the end of his reign as Mob ruler of New York, but he merely viewed it as a challenge to his ingenuity. There were many points of entry back into the United States, and the authorities couldn’t keep him away from his criminal pals.

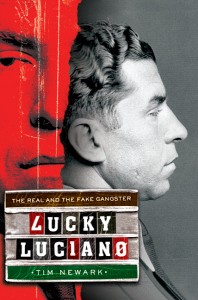

Excerpted from Lucky Luciano: The Real and the Fake Gangster by Tim Newark. Copyright © 2010 by the author and reprinted by permission of Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.

TIM NEWARK is author of Lucky Luciano: The Real and the Fake Gangster, Mafia Allies: The True Story of America’s Secret Alliance with the Mob in WWII, and The Fighting Irish: The Story of the Extraordinary Irish Soldier, editor of Military Illustrated, and has contributed book reviews to the Financial Times, Time Out, and Daily Telegraph. He has worked as a scriptwriter and consultant for seven TV documentary series for the History Channel and BBC Worldwide. He lives in London.