by Philip Jett

“Did Jett Betray Me?”

Many years before Ancestry.com, my uncle researched the genealogical history of the Jett family and discovered some were Virginian colonists of English descent. My father, however, did not share his brother’s inquisitiveness. “Just check the prison records,” he remarked. At the time, I was reading an account of the Lincoln assassination entitled, Twenty Days, by Dorothy and Philip Kunhardt Jr., and made a discovery of my own. More than forty years later, I was reintroduced to my find while watching Smithsonian Channel.

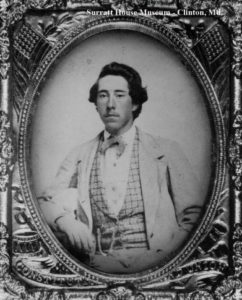

William Storke Jett, or Willie, was a Confederate soldier in the 9th Virginia Cavalry, Company C. After Lee’s surrender, Willie and others rode for Richmond to sign an oath of allegiance to the United States. Along the way, they stopped at a ferry crossing in Port Conway, Virginia. It was beside the Rappahannock River that eighteen-year-old Willie stumbled into the history books.

“What command do you belong to?” asked a stranger as a uniformed Willie tied up his horse. “I have my brother, a Marylander, who was wounded in a fight below Petersburg . . . I suppose you are all going to the Southern army. We are anxious to get there ourselves and wish you to take us along with you.”

The stranger persisted with his appeals. He seemed anxious; his voice even trembled at times. Suspicious, Willie refused and walked away. The stranger stopped him near the wharf. “We are the assassinators of the president,” he whispered. “Yonder is J. Wilkes Booth, the man who killed Lincoln. My name is David Herold.”

Willie later described himself as “confounded” for “two or three minutes.” Booth saw Herold talking with Willie and approached on crutches. A shawl draped over Booth’s left arm slipped as he neared and revealed “J.W.B.” tattooed on his left hand. Herold pleaded with Willie to hide them, whereas Booth was aloof, perhaps too arrogant to beg or simply resigned to his fate. Willie finally relented.

They crossed by ferry to Port Royal where Willie knew a few residents. After trying two houses without success, Willie led Herold and Booth on horseback two miles out of town to Richard Garrett’s farm. He asked Booth about the assassination and was surprised by his answer: “It’s nothing to brag about.” When they reached the farm, Willie convinced Garrett to take in the “Boyd” brothers for a day or two since one was wounded. Willie then rode to the Star Hotel in nearby Bowling Green.

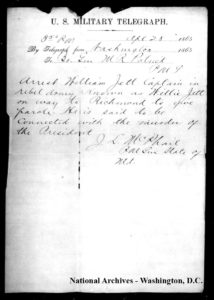

The following day, a US cavalry patrol learned from the ferryman that Booth was traveling with a man named Willie Jett. Consequently, the local provost marshal received a telegram from Washington to arrest Willie for being “connected with the murder of the President.”

Around midnight, Union soldiers burst into Willie’s room with guns drawn. Willie claimed no knowledge of Booth, but as voices grew louder and gun barrels drew nearer, his memory returned. He was arrested and after receiving assurances that “he would be protected from blame,” Willie agreed to lead them to Booth.

Not long after they arrived at the Garrett farm, Booth refused to surrender and was shot inside a tobacco barn. The bullet severed his spinal cord. “Tell mother I die for my country,” the paralyzed Booth muttered to a Union cavalryman. Booth later requested to see his hands and spoke what is generally reported to be his last words, “Useless, useless.” However, according to the sworn testimony of a lieutenant colonel and a provost marshal detective, Booth subsequently heard Willie Jett’s name mentioned and spotted him standing nearby. He attempted to cough and then asked, “Did Jett betray me?” before passing into unconsciousness. Booth died shortly after dawn on April 26, 1865, twelve days after Lincoln’s assassination.

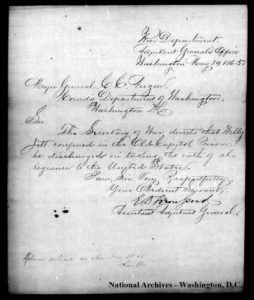

Willie and Herold were escorted to Washington, DC and imprisoned in the Old Capitol Prison with other conspirators. Though he could have hanged, Willie served as a witness during Herold’s trial and was released. Herold was hanged with three other conspirators.

Willie and Herold were escorted to Washington, DC and imprisoned in the Old Capitol Prison with other conspirators. Though he could have hanged, Willie served as a witness during Herold’s trial and was released. Herold was hanged with three other conspirators.

Willie later married and became a Baltimore businessman before dying at age thirty-seven in a Williamsburg, Virginia, mental asylum, presumably from advanced syphilis. He is buried in Fredericksburg.

Though I have not yet determined how closely Willie is related to me, it appears my father was correct. If my uncle had simply checked prison records, he would have discovered William Storke Jett—the young man who chanced upon, assisted, and then betrayed Abraham Lincoln’s murderer.

I’d enjoy reading about your famous or infamous relatives from history. Please comment if you’d like to share.

Interested in reading more from Philip Jett? Check out “Can Violence Be Genetic and Inherited? Consider My Family’s Tales of Grisly Murder” on CriminalElement.com!

PHILIP JETT is a former corporate attorney who has represented multinational corporations, CEOs, and celebrities from the music, television, and sports industries. He is the author of The Death of an Heir: Adolph Coors III and the Murder that Rocked an American Brewing Dynasty. Jett now lives in Nashville, Tennessee.