dd

dd

dd

By Dwight Jon Zimmerman and John D. Gresham

OPERATION RED WINGS

American forces in Afghanistan knew that terrorists were planning to do everything they could to sabotage the elections, from trying to stop people from voting to assassinat- ing the newly elected officials. To interdict Shah’s attempts in the area, Marine Major Tom Wood, the operations officer of the marine battalion based in the region, created a plan that was a joint Marine Corps and special operations mis- sion, code-named Operation Red Wings. (Later accounts, publications, and web sites would incorrectly refer to the mission as Redwing or Red Wing.)

American forces in Afghanistan knew that terrorists were planning to do everything they could to sabotage the elections, from trying to stop people from voting to assassinat- ing the newly elected officials. To interdict Shah’s attempts in the area, Marine Major Tom Wood, the operations officer of the marine battalion based in the region, created a plan that was a joint Marine Corps and special operations mis- sion, code-named Operation Red Wings. (Later accounts, publications, and web sites would incorrectly refer to the mission as Redwing or Red Wing.)

Though Shah and his cadre were the targets, their capture or deaths was just the first, short-term goal of Red Wings. A second part addressed the long-term goal the marines had for the region, the improvement of the lives of the villagers. To accomplish both goals, Major Wood broke Red Wings down into five phases: the first two were to be led by special operations, the other three handled by the marines. The first phase involved reconnaissance and surveillance by a SEAL team to identify and confirm the location of Shah and his men. The second phase called for two SEAL teams to be inserted into the area: one to kill or capture Shah and his cohorts, and a second to establish a security cordon to prevent counterattacks.

GETTING READY

Major Wood presented his plan to his SEAL counterpart, Lieutenant Commander Erik Kristensen, who would exercise command over the first two stages. Kristensen changed some of the details. Instead of having his teams enter the suspected area on foot, as Wood proposed, he planned to use the time-tested special operations tactic of a night helicopter insertion by fast rope—troops would rappel down swinging rope lines as quickly as possible. As the noise of the helicopter would inevitably alert anyone nearby, the tactic included a two-part diversion designed to get Shah and his supporters to lower their guard by getting them used to the helicopters’ presence. The first was a series of “dummy drops” conducted during the night leading up to the actual drop itself. Then, on the evening of the real drop, a second helicopter would accompany the one with the SEAL inser- tion team, and, shortly before and after the drop, it would conduct a series of touch-and-go fake landings on a number of locations in the immediate area to confuse any listeners.

The rugged terrain posed serious communications prob- lems. The deep, rocky valleys created numerous line-of-sight blackout areas affecting radio transmissions and reception.

The only radio known to have totally overcome this problem was the powerful (20 watt) PRC-117. But the PRC-117 was big (3 inches high, 10.5 inches wide, and 9.5 inches deep) and heavy—almost 10 pounds without its rechargeable lithium battery. The decision was made to go with the smaller PRC- 148 MBITR (“em-biter”) containing a computer chip that allowed it to make a secure link with a communications satellite.

Kristensen chose Lieutenant Michael P. Murphy to lead the team that would attempt to engage Shah with sniper fire. Unfortunately, the rocky and forbidding terrain and lack of locations with sufficient ground cover for camouflage meant that Kristensen would have to deploy just four men, the smallest possible team. The three SEALs along with Murphy were Navy Hospital Corpsman Second Class Marcus Luttrell, Petty Officer Second Class Matthew G. Axelson, and Petty Officer Second Class Danny P. Dietz. Luttrell and Axelson would be the snipers/shooters, and Murphy and Dietz would serve as spotters. The mission was to last no more than four days.

Meanwhile, Major Wood’s brilliant intelligence officer, Captain Scott Westerfield, had succeeded in compiling a rather complete dossier on Shah and his operation. Wester field identified four likely locations where Shah and his men could be expected to appear on or around June 28. Two were on the east side of the mountain Sawtalo Sar, and two others were on the west. Meetings were held to review the Predator unmanned aerial vehicle images of the area and identify observation and ambush sites, helicopter insertion sites, and landing zones. The decision was made to insert the team about a mile south of the nearest observation and ambush site, near the summit of Sawtalo Sar, the idea being that it’s easier to travel downhill. The team would then advance as fast as possible with the goal of reaching the first observation and ambush site around dawn. They would be traveling light, carrying only about forty-five pounds of gear each. Ominously, all four men had a premonition about the mission. As they made their final preparations, each added extra magazines to their load, just in case.

INTO THE ENEMY’S BACKYARD

On the night of June 27, 2005, Lieutenant Mike Murphy and his men boarded the MH-47 Chinook that would ferry them to their mountaintop landing zone. The helicopter then took off from Bagram Air Base into the cold night sky and headed to their destination. Forty-five minutes later the Chi- nook hovered twenty feet above their landing site. The four SEALs quickly rappelled to the ground on the fast rope. Within seconds, the Chinook was gone, and the SEALs were on their own.

It was supposed to be a covert drop, with the only indi- cation of their arrival being the sound of the helicopter’s rotors. But a mistake had been made. The helicopter’s crew chief, accustomed to direct-action raids where speed, not secrecy, is paramount, had accordingly detached the fast rope, allowing the olive-drab line to fall to the ground. In plain view of anyone who might come along during the day was a thirty-foot-long piece of evidence that Americans were there. Groping over the rugged terrain in the gloom, Murphy and Axelson grabbed tree branches and other veg- etation to cover it. Luttrell, meanwhile, got on his radio and contacted the AC-130 gunship riding shotgun overhead:

“Sniper Two One, this is Glimmer Three—preparing to move.”20 After getting confirmation, and with the partially coiled rope now hidden as best they could, the team shoul- dered their rucksacks and began their trek to their observation and ambush site.

It was monsoon season in India, which meant that Afghanistan was subject to unpredictable thunderstorms and thick fog. One storm burst over the SEAL team shortly after they landed. The cold, wind, rain, and steep terrain overgrown in places with thick vegetation made the trek a test of endurance and skill. They managed to reach the near- est of the two designated observation and ambush sites near dawn. Though the location offered a clear view of the val- ley and village below them, it did not provide adequate shelter, and the SEALs were vulnerable to being discovered by a passing local such as a goatherd (what’s known as being “soft compromised”).

Shortly after they took up position, a thick fog bank moved in between the SEALs and the village below. They realized that if fog appeared once, it would probably appear again. They would have to move. Murphy took Axelson with him and began searching for a nearby site that wouldn’t be affected by the weather and that would, he hoped, offer them some protection from detection. After about an hour, he returned and told Dietz and Luttrell they had found one about a thousand yards away.

The new location proved to be better for observation and sniping—they had a clear and unobstructed view of the entire village. If Shah were there, they’d spot him in an instant. Unfortunately, the new site was even more exposed than the first, with only one convenient path in and out. If

they were spotted and that path cut off, they’d have to either shoot their way out or attempt to escape down the danger- ously steep mountain slope.

FATAL DISCOVERY

The SEALs got into position and began their observation. The morning passed quietly. Then, at about noon, Luttrell heard the sound of approaching footsteps. Minutes later three goatherds and about a hundred goats appeared. The SEALs quickly surrounded and detained them. Danny Dietz, responsible for communicating with headquarters, got on his radio and sent back a faint, scratchy message that sent a chill down the backs of the men at headquarters, “We’ve been soft compromised.”21 The operation had just gone wrong—to what extent remained to be determined.

The SEALs began discussing their options. None of the al- ternatives facing them were attractive. The three Afghans, one a boy, were clearly goatherds—they did not have firearms, their only “weapon” an ax for chopping wood. Though the Afghans were able to tell the SEALs that they were not Tal- iban, that didn’t mean they weren’t sympathizers or that they wouldn’t tell the Taliban or Shah’s men of the SEALs’ location if they were set free. Worse, Dietz was having com- munications problems. He wasn’t sure his first message had been received. What he did know was that he would not be getting any answer back. The team was in a radio blackout area. After a short debate in which votes were taken, according to Marcus Luttrell, Lieutenant Murphy confirmed their decision: “We gotta let ’em go.”22 The Afghans and their goats were allowed to leave.

Five minutes after the goatherds had disappeared down the

they were spotted and that path cut off, they’d have to either shoot their way out or attempt to escape down the danger- ously steep mountain slope.

FATAL DISCOVERY

The SEALs got into position and began their observation. The morning passed quietly. Then, at about noon, Luttrell heard the sound of approaching footsteps. Minutes later three goatherds and about a hundred goats appeared. The SEALs quickly surrounded and detained them. Danny Dietz, responsible for communicating with headquarters, got on his radio and sent back a faint, scratchy message that sent a chill down the backs of the men at headquarters, “We’ve been soft compromised.” The operation had just gone wrong—to what extent remained to be determined.

The SEALs began discussing their options. None of the al- ternatives facing them were attractive. The three Afghans, one a boy, were clearly goatherds—they did not have firearms, their only “weapon” an ax for chopping wood. Though the Afghans were able to tell the SEALs that they were not Taliban, that didn’t mean they weren’t sympathizers or that they wouldn’t tell the Taliban or Shah’s men of the SEALs’ location if they were set free. Worse, Dietz was having com- munications problems. He wasn’t sure his first message had been received. What he did know was that he would not be getting any answer back. The team was in a radio blackout area. After a short debate in which votes were taken, according to Marcus Luttrell, Lieutenant Murphy confirmed their decision: “We gotta let ’em go.” The Afghans and their goats were allowed to leave.

Five minutes after the goatherds had disappeared down the

trail, the SEALs had shouldered their gear and were double-timing in the opposite direction. Even though they planned to continue their mission (aborting the mission had not been discussed), they knew they couldn’t stay where they were. They retraced their route to their original location and once again took up position there.

As the minutes ticked by, it appeared that perhaps the herders had not told the insurgents about them. But, about two hours after they had released the Afghans, the SEALs started hearing the noise of movement above and to the left of their position. A large insurgent force that they initially estimated to be at least eighty men, armed with AK-47 assault rifles and RPG launchers, was approaching their position.

Evidence from the ensuing engagement, plus a video of the attack—one of two made by Shah—indicates the Afghan force may have been smaller than the SEALs estimated. Murphy’s Medal of Honor citation puts the number between thirty and forty. Regardless, the fact was that Shah was intimately familiar with the terrain and knew how to use it to best advantage. And he did, attacking from above with his men spread out. Most devastating of all, unlike the SEALs, Shah possessed good communications. He had a commercial two-way radio that somehow was not affected by the blackout that nullified the SEALs’ radios, and he expertly used it to position his men where they would be the most effective. But if the SEALs could manage to buy some time, with their superior training they stood a good chance of turning the tables on Shah and his men. And, therefore, time was the one thing Shah was determined not to give them.

Lieutenant Murphy immediately ordered Dietz to again try to raise headquarters in Bagram, this time for help. And, once again, because of the terrain and atmospheric conditions, Dietz could transmit but not receive messages; at Bagram, the words that everyone there hoped they wouldn’t hear came over the loudspeaker: “Contact! We’re hard compromised!” A rescue mission was needed immediately, and preparations were made to launch it.

Meanwhile, the others quietly took aim as the insurgents spread out to the left and right in a classic flanking maneuver. When the lead fighters were about twenty yards from their position, the SEALs opened fire. As hell erupted around them, Dietz delivered more unwelcome news. Once again, he told them he couldn’t establish contact with head-quarters. Strictly speaking, that wasn’t the case. Dietz had been able to reach headquarters, he just didn’t know it.

With their escape route blocked by a superior force in a superior position, and with fighters about to surround them, Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to retreat down the mountain. After slipping, sliding, and rolling helter-skelter down the rocky slope, with bullets constantly whizzing about them, Luttrell and Murphy landed hard on a piece of flat ground some distance below their outpost. Luttrell would later discover he had cracked some vertebrae. Mur- phy was wounded—shot in the abdomen. Axelson and Dietz soon joined them. Dietz was wounded, too: his right thumb had been shot off.

Unfortunately, Luttrell, their corpsman, had lost his medical supplies during the descent. There was nothing he could do to help either Murphy or Dietz. Worse, the gunfire from the insurgents had not let up. Their only hope for survival was to keep traveling down the steep slope toward the village far below. If the SEALs could get inside one of the huts, they’d have a better chance of holding out against the enemy.

Once again, as the Afghans closed, Lieutenant Murphy ordered the SEALs to jump. They next landed on a small escarpment about thirty feet below. The insurgents, mean- while, maintained a steady rate of heavy fire at the retreat- ing SEALs. Dietz was hit twice more. Though he was severely wounded, they had to keep going. Axelson and Lut- trell took the lead in the descent and, after they reached the next position, provided cover fire for Murphy and Dietz.

The running firefight continued, with the SEALs having to also engage insurgents who had managed to get into position ahead of them. This time, though, there were only three SEALs able to fight. Dietz was dead, and the others were forced to leave their comrade’s body behind. Somehow, Murphy, Axelson, and Luttrell managed to run the gauntlet of RPGs and bullets as they continued their descent. But there were too many enemy fighters and too many bullets. Axelson was hit, in the chest and head.

A CALL FOR HELP

After the three had reached their latest defensive position, Lieutenant Murphy knew he had to make his call now, or it would be too late. He took out his Iridium satellite phone and tried to call. The signal was blocked by the rocks above him. The only way he’d be able to connect with the com- munication satellites was to move out in the open. Moments later, and in clear view of the enemy, Lieutenant Michael P. Murphy moved out from cover and hit the speed-dial button on the phone.

This time, he got through.

Ignoring the AK-47 bullets ricocheting off the hard ground around him, Murphy said, “My men are taking heavy fire… we’re getting picked apart. My guys are dying out here . . . we need help.”

Just then, an AK-47 round struck him in the back and burst through his chest. The impact knocked Murphy for- ward and caused him to drop his rifle and phone. Somehow, he managed to reach down and pick both up. After listen- ing on the phone for another moment, he replied, “Roger that, sir. Thank you.”25 Then he hung up and staggered back to his fellow SEALs.

Rescue was finally on the way.

The three surviving men were SEALs, but they were not supermen. Lieutenant Murphy managed to reach a defen- sive position on a section of the slope above Marcus Luttrell and Matthew Axelson before he was finally gunned down. Seconds later, the concussion from an RPG explosion knocked Luttrell down the slope, an event that ultimately helped save his life and made him the only survivor of the ordeal. Luttrell’s last sight of Axelson was of him using his sidearm; Axelson had three magazines left for his pistol. When a search party found his body days later, only one magazine remained unused. But as badly as the mission was turning out, what was about to happen would mark June 28, 2005, as one of the worst in U.S. special operations history.

As the SEAL team was being cut down, the attempted rescue had ended in disaster. A quick reaction force of two MH-47D Chinooks, four MH-60 Blackhawks, and two AH-64D Apache Longbow helicopters was dispatched from Bagram to try and extract the surviving SEALs. As they flew into the target area, however, they ran into a trap and were subjected to a fusillade of RPG fire, just as had happened twelve years earlier during the infamous “Black Hawk down” firefight in Mogadishu, Somalia. One RPG flew into the open rear ramp door of one of the Chinooks, causing it to lose control and crash into a ravine. The helicopter was destroyed and all personnel aboard, including sixteen SEALs, were killed. Nineteen highly trained special operations warriors and a valuable MH-47 Chinook helicopter had been lost, and Operation Red Wings was a complete disaster.

Somehow, Marcus Luttrell survived. Though suffering numerous shrapnel wounds in addition to his other injuries, he managed to evade the enemy long enough to be discov- ered by a friendly villager who, following the tradition of Pashtunwalli—a generations-old blood code of hospitality— protected him from Shah and his men. Meanwhile, one of the largest U.S. search-and-rescue operations since Vietnam was trying to locate any survivors from the SEAL team, with three hundred personnel committed to the effort. Members of the army’s Seventy-fifth Ranger Regiment finally rescued Luttrell on July 2, five days after Murphy and his team had dropped onto the side of the mountain. A village elder had brought a note from Luttrell to a nearby marine encampment, describing his location and condition.

The 62nd Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer, Pre-commissioning Unit (PCU) Michael Murphy (DDG 112) is christened during a ceremony in Bath, Maine. Credit: Petty Officer 1st Class Tiffini Jones Vanderwyst

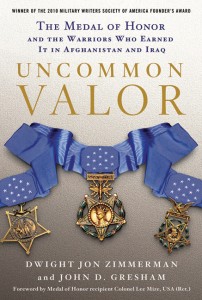

Excerpted from Uncommon Valor: The Medal of Honor and the Six Warriors Who Earned It in Afghanistan and Iraq by Dwight Jon Zimmerman and John D. Gresham. Copyright © 2010 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

DWIGHT JON ZIMMERMAN is an award-winning author of books, including Uncommon Valor: The Medal of Honor and the Six Warriors Who Earned It In Afghanistan and Iraq, and articles on military history and a member of the Military Writers Society of America.

JOHN D. GRESAHM is a veteran analyst and the co-author, with Tom Clancy, of Clancy’s bestselling nonfiction series, including Special Forces: A Guided Tour of the US Army Special Forces and Fighter Wing: A Guided Tour of the an Air Force Combat Wing. He is also the author of Uncommon Valor: The Medal of Honor and the Six Warriors Who Earned It In Afghanistan and Iraq.