By James L. Nelson

The Provincial Congress was worried. It was losing control of the army.

Joseph Warren had warned about this possibility when he first wrote to the Continental Congress urging them to take control of the armed forces and suggesting the possibility of a military government. In a private letter to Sam Adams he was more direct. He warned that “unless some authority sufficient to restrain the irregularities of this army is established, we shall very soon find ourselves in greater difficulties than you can well imagine.”

Rumors and character assassinations were becoming common in the army and swept through the ranks like a communicable disease. Worse, the soldiers were beginning to take liberties with the private property of those who lived near the camps. Warren explained to Adams how the troops had first turned out with “nothing but the clothes on their backs, without a day’s provisions, and many without a farthing in their pockets.” The Patriots gave willing assistance to the soldiers, and where assistance was not given by those of a Loyalist bent, it was taken. “Prudence seemed to dictate,” Warren wrote, that such liberties, born of necessity, “should be winked at.”

Unfortunately, the attitude that the troops could simply take what they needed was becoming widespread and ingrained, and fewer distinctions were made between the property of Patriot and Loyalist. Warren, eager to find justification for the behavior of his countrymen, pointed out, somewhat weakly, “It is not easy for men, especially when interest and gratification of apatite are considered, to know how far they may continue to tread in the path where there are no land- marks to direct them.”

The troops were also becoming more defiant of the orders of the Provincial Congress. Warren urged that the Continental Congress find a solution quickly, “as the infection is caught by every new corps that arrives.” It was understood, at least by those in the Massachusetts government, what the solution required. A real civil government with the force of law had to be established in the colony, the army had to come under the direction of the Continental Congress, and the Congress needed to appoint a commander in chief who wielded more authority than Artemas Ward and who would bring the troops back into line before it was too late.

“You may possibly think I am a little angry with my countrymen,” Warren wrote, and then assured Sam Adams that he was not. Warren tried hard to be circumspect and nonjudgmental. “It is with our countrymen as with all other men,” he wrote, “when they are in arms, they think the military should be uppermost.”

Joseph Warren may have been more inclined to see the problems as a temporary aberration, given that he, more than any other political leader in Massachusetts, was drawn to the military side of the rebellion. He was certainly not the only one to perceive the problem.

Elbridge Gerry, representative to the Provincial Congress from Marblehead and later signer of the Declaration of Independence, wrote to the Massachusetts delegates in early June. The people, he pointed out, had a very strong sense of their rights, since the rights of the colonies was the point that had been hammered home for so long in the growing dispute with En gland. Gerry wrote:

They now feel rather too much their own importance, and it requires great skill to produce such subordination as is necessary. This takes place principally in the Army. They have affected to hold the military too high, but the civil must be first supported.

The problems between the civilian leadership and the military were apparently so widespread that word even reached the Loyalists holed up in Boston. Peter Oliver wrote to a friend, “The Army at Cambridge damn the Congress Orders, and the Congress are afraid of the Army, and Putnam will manage them all.”

Gerry, like Warren, was looking to the Continental Congress to help establish a civil government in Massachusetts. Like Warren and others, too, he felt that “a regular General to assist us in disciplining the Army” was needed. Such a general, he felt, could train the Americans in a year or less “to stand against any troops, however formidable they may be with the sounding names of Welsh Fusileers,Grenadiers, &c.”

Despite his being current commander in chief of the Massachusetts army, Artemas Ward was not mentioned for command of the Continental Army, not by Gerry or anyone else. There seems to have been a tacit understanding that Ward was not the man for the job.

There also seemed to be a growing consensus, at least among a certain faction of Massachusetts’s leaders, as to who should be in the post of commander in chief. Gerry’s letter closely echoes the earlier letter by James Warren on the subject. Gerry felt Charles Lee might “render great service by his presence and councils,” though he knew “the pride of our people would prevent their submitting to be led by any General not an American.”

“I should heartily rejoice to see this way the beloved Colonel Washington,” Gerry continued, “and do not doubt the New- England Generals would acquiesce in showing to our sister colony, Virginia, the respect which she has experienced from the Continent, in making him Generalissimo.” Gerry stated that Joseph Warren agreed with him on that point. John Adams, also a supporter of Washington, later claimed to have been the one to nominate him for the post of commander in chief. With the exception of John Hancock, who wanted the job for himself, the New En gland leadership seemed pretty well aligned behind Washington for head of the army.

Though the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was growing frustrated and impatient, the Continental Congress was in fact considering its various requests. On June 9 the delegates passed a resolution concerning the civil government of the colony. In it, they declared that no obedience was due the act of Parliament that altered the charter of Massachusetts or to any governor or lieutenant governor who would act to subvert the charter. Therefore, those offices were to be considered vacant.

There was no legislature, either, since Gage had suspended it. Taken altogether, the Congress was of the opinion that no government currently existed in Massachusetts. The situation could not continue that way; “the inconveniences, arising from the suspension of the powers of Government, are intolerable,” particularly given that General Gage had begun waging war.

The Congress was trying to tread a fine line between allowing Massachusetts to form a government and giving permission for anything that looked like a declaration of independence, which many in the Congress were wary of. It recommended, therefore, that each town in Massachusetts choose a member for an assembly, which would function as a lower house, and that assembly should then elect a council, which would form an upper house. Then the “assembly and council should exercise the powers of Government, until a Governor, of his Majesty’s appointment, will consent to govern the colony according to its charter.”

It was a decent compromise, and pretty much what Massachusetts already had with the Provincial Congress and the Committee of Safety. It gave the leaders in Massachusetts the permission they sought to form a new government, while assuring the more conservative members of Congress that they were not doing anything so radical as throwing off the authority of the king by forming a new government. The resolution ignored the fact, of which they were all perfectly aware, that Governor Thomas Gagewas a governor of His Majesty’s appointment. What they wanted was a governor appointed by the king who would take their view that the king had no right to alter the charter. That was something they were not likely to get.

Congress’s adopting the army was a more ambiguous process. On June 10, Hancock, as president of the Continental Congress, wrote to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress that “the Congress have been so pressd with Business that they have been prevented Determining upon the other matters mentioned in your Letters,” by which he meant taking over the army.

Though Hancock claimed that the Congress had had no time to consider the administration of the army, it had been considering army affairs. On the day after Benjamin Church arrived in Philadelphia with letters from the Provincial Congress, a committee was appointed to “borrow the sum of six thousand pounds for the use of America . . . and that the sd [said] com[mittee] apply the sd sum of money to the purchase of gunpowder.” The most interesting aspect of this was that the gunpowder was, according to Congress, “for the use of the Continental Army.”

It is the first official use of the term “Continental Army.” Though there was no formal vote to adopt the army, at least none that was recorded, the Congress began increasingly to think of the troops around Boston as a national army under its direction. On June 9 it requested that New York forward to Massachusetts five thousand barrels of flour for the Continental Army. Colonies as far south as Mary land were asked to collect saltpeter and sulfur for the manufacture of gunpowder “for the use of the continent.”

On June 14 the Congress voted to raise “six companies of expert riflemen” from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia to “join the army near Boston”— the first time Congress had actually authorized men for the military— and drafted an enlistment form that signified that those who signed were enlisting as “a soldier, in the American continental army.” That same day a committee consisting of George Washington, Philip Schuyler, who would serve as a major general, Silas Deane, Thomas Cushing, and Joseph Hewes was convened to “bring in a dra’t of rules and regulations for the government of the army.”

Bit by bit the Continental Congress was taking over the organizing, running, and financing of the army around Boston. Before that transition was complete, the ad hoc force that had developed out of the Lexington Alarm would be put to one last, bloody test.

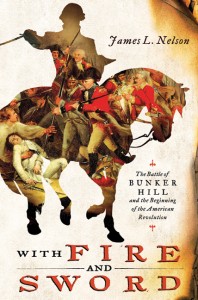

Excerpted from With Fire and Sword: The Battle of Bunker Hill and the Beginning of the American Revolution by James L. Nelson.

Copyright © 2011 by the author and reprinted by permission of Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

JAMES L. NELSON is the author of With Fire and Sword: The Battle of Bunker Hill and over a dozen other historical fiction and nonfiction works, and has won the prestigious American Library Association/William Young Boyd Award, the country’s top award for military fiction. Novelist Patrick O’Brian called him “a master of his period and of the English language.” He has lectured around the country and has appeared on the Discovery Channel, the History Channel, and C-SPAN’s Book-TV. He lives in Harpswell, Maine with his wife and four children.