by Michael Bornstein and Debbie Bornstein Holinstat

It was March 1941. Nearly a year had passed since I had been born, and despite my parents’ continued optimism, conditions were getting worse, not better.

Still, Żarki remained an open ghetto and, for that, families were thankful. Everyone returned to his own home each night. And now Papa had an important role inside our community. Right after I was born, the Nazi government declared that every ghetto and town in Poland must have a Judenrat—a formal council of Jewish leaders. The Nazi regime declared that these leaders would help the German army enforce rules and maintain order among Jews. Membership on the Judenrat was not necessarily a coveted role. Jews quickly came to view Judenrat leaders as traitors, assisting the enemy. Papa wasn’t given a choice, though. The elders in his own Jewish community selected him to be president of Żarki’s Judenrat.

He hated that title—president—and he loved it at the same time. He dreaded the looks from neighbors who viewed him as one step removed from the Nazi enemy. He also prayed that his role could help him save the family.

“Why worry so much, Israel?” Mamishu would ask. “You don’t have a choice. You fret so much about things you can’t control.”

It was true. Papa simply had to do his best to protect those he could. He had a plan, too. Maybe it was too radical, too risky. He had to try to make the most of his position, though.

“Sophie, do you think money can talk louder than weapons?” Papa asked her one night.

It was a weekday evening and Mamishu was in the kitchen boiling red berries in a pan over the stovetop to make compote. She may not have known exactly what he meant, but she probably had a feeling about where this conversation was headed.

“I think you need to follow the Germans’ orders, stay quiet, and stop plotting,” she told him. “Stop thinking so much, Israel. You should have realized by now that our best hope is that the war ends. It’s only a matter of time.”

Papa said nothing. And since he didn’t protest, Mamishu continued. She had been at her mother’s house that morning and had seen a copy of an underground newspaper—a newspaper that was being printed and distributed secretly among Jews in the region.

“Israel, did you see the newspaper? It says Britain is pressuring the United States to join the Allied forces who are fighting the Nazis. If America joins the British, the German army will crumble. It’s going to happen, and if—”

“Just hear me out, Sophie,” Papa said, cutting her off gently. “I was thinking . . . there’s still so much wealth here in Żarki. The Zimleichs have thousands of zlotys hidden underground, just like us. So do the Birnbaums and the Heitels. If I can gather enough funds, perhaps I can persuade some soldiers to loosen the rules a little around here. The German guards don’t speak Yiddish, but the language of money must be universal.”

[ . . . ]

Every Monday, Papa met early in the morning with Officer Schmitt, the head of the local Gestapo—the Nazi police— in the region. Not long after Papa was named Judenrat president, Officer Schmitt had assigned Papa to the role of Judenrat police chief as well. This was a role my father especially feared holding. What if he was ordered to kill a fellow Jew? What if he was forced to impose brutal restrictions or jail innocent neighbors? It was the reason a lot of Żarki residents were distrustful of my father. He had a reputation for being kind, but when you give a man power and a title, it could change him. Jews had, after all, witnessed what effect that had had on the band of Polish guards.

The Monday after the guards arrived in the ghetto, Papa stuffed his pants pocket with Polish banknotes. He and other Judenrat members had collected more than two thousand zlotys at a time when money was immeasurably scarce. That would be the equivalent of about five hundred dollars today. Papa knew the time had come to use the first batch of collected money.

My father gathered his courage as he approached the town’s former bootmaking shop, which the Gestapo had taken over and was now using as a base. He knew that Officer Schmitt was likely to be alone, since his soldiers always walked the streets at that hour, looking for suspicious activity as the sun came up over Żarki. Aside from the patrols, the town was mostly quiet.

Fear had heightened my father’s senses so that the smell of leather buried deep in the walls was almost overpowering as he entered the room. The shuffle of his own feet had never sounded louder, and he could feel his heart racing as he stepped in front of the Gestapo leader.

“Officer Schmitt,” Papa said in his developing German tongue. “I’d like to speak with you about the new guards.” Creak. His shoes made noise as he shifted weight. “They are making it more difficult for me to maintain my own people’s trust. The guards—they are ruthlessly beating Jews in the ghetto. There does not seem to be reason behind their attacks. They are simply attacking at random, without provocation or cause.”

Officer Schmitt was quiet a moment. Papa could hear only his breathing.

Then he stood up and walked over to my father. “Surely, Bornstein, you aren’t intending to complain. You should be lying down at my feet and thanking me, your town has it so good. Jews across this country are sleeping behind barbed-wire fencing and iron bars. You go home to your soft pillows and wool quilts each night. I’ll tell you what becomes of complainers. Last month—”

“Officer Schmitt,” Papa interrupted. “I wondered simply if anything might inspire you to reassign the Polish guards somewhere outside Żarki. My community is willing  to do anything at all to see that your needs are met. Please, Officer Schmitt, give it some thought.”

to do anything at all to see that your needs are met. Please, Officer Schmitt, give it some thought.”

Glaring at my father, Schmitt pulled his Luger from its holster and then pressed the tip of his pistol into Papa’s forehead. With the barrel against his skull, Papa had never before had his ability to stay calm tested so dramatically. And yet he didn’t flinch as Schmitt—with the smell of Sobieska vodka wafting off his lips—whispered, “You will not ever interrupt me again. I am an officer of the Third Reich, you dirty Jew!” “Of course,” Papa said. “I intend no disrespect, Officer Schmitt. I only wanted to provide you with assistance however you may require it.”

The meaning for Papa’s emphasis on the word “however” finally resonated with Schmitt. Papa watched as the switch seemed to click in the officer’s malevolent mind. When a few moments had passed and Schmitt still had not pulled the trigger, Papa wordlessly reached into his pocket and pulled out the banknotes.

It was so bold a move—bribing an officer of the German police!—that Schmitt almost laughed. He had to admit, he said, that Israel Bornstein had guts. Schmitt probably could have used that extra cash, too. Wartime had put a strain on every family, even in Germany.

“Why don’t I just take this cash and replace it with a bullet in your brain?” Schmitt asked, his dark eyes blazing.

Papa had no choice but to be direct. “I believe there is more where this came from, Officer Schmitt. But I’m afraid I’m the only person who can collect such discreet funds from the community. A bullet won’t find you more buried treasure.”

Within twenty-four hours of that conversation, the band of barbarous guards in Żarki was reassigned to a neighboring town. They never returned.

When a thirteen-year-old boy was arrested for missing a day of work in Żarki and his sentence was death, the jailhouse doors suddenly opened after Papa appeared with a large satchel at the front of the prison.

My father used the Judenrat fund to obtain two hundred legal travel visas for families desperate to escape Żarki. Many of those families made it all the way outside the borders of Poland to find safety and refuge. Hundreds more were able to escape through the woods at night or hide in bunkers with money from the Judenrat to sustain them. Papa’s plan was working.

And so it went for about a year. Kosher butchers were forbidden from properly preparing meat for Jewish meals in Poland, but in Żarki, the kosher butcher’s life was spared because of the Judenrat’s deliberately spent funds. The last of the open ghettos in Poland were being shut down and inhabitants deported to camps, but Jews in Żarki slept in their own beds, with their families, inside a world protected by money—and by at least one very greedy German police officer.

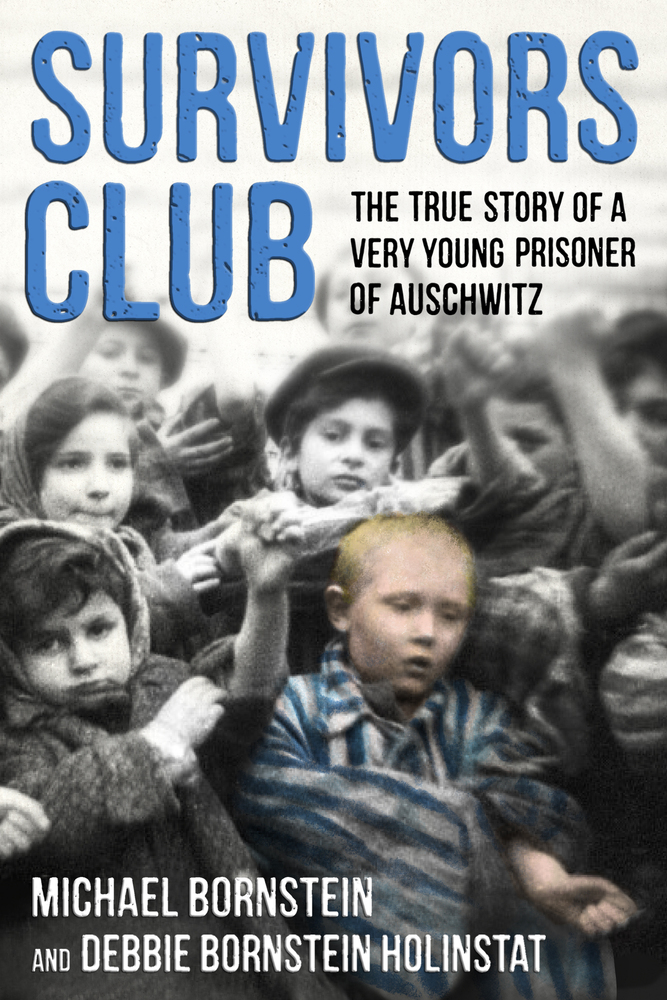

Michael Bornstein survived for seven months inside Auschwitz, where the average lifespan of a child was just two weeks. Six years after his liberation, he immigrated to the United States. Michael graduated from Fordham University, earned his Ph.D. from the University of Iowa, and worked in pharmaceutical research and development for more than forty years. Now retired, Michael lives with his wife in New York City and speaks frequently to schools and other groups about his experiences in the Holocaust.

Debbie Bornstein Holinstat is Michael’s third of four children. A producer for NBC and MSNBC News, she lives in North Caldwell, New Jersey. She also visits schools with her father, and has been working with him for two years, helping him research and write his memoir, although she has grown up hearing many of these stories her entire life.