By Paul Ham

Upon his swearing in as President Harry Truman’s Secretary of State, on 3rd July 1945, James Francis ‘Jimmy’ Byrnes quietly assumed greater powers than his new position entailed. In coming weeks, Byrnes would act as Truman’s big brother and almost as a de facto president.

On one issue Byrnes appeared utterly uncompromising. It was that America should never waver from her insistence on the ‘unconditional surrender’ of Japan.

The new Secretary had hitherto been crystal clear by what he meant by ‘unconditional surrender’: it meant the dismantling of the Japanese Imperial system and putting the Emperor on trial as a war criminal.

Truman would be ‘crucified’ if he accepted anything less than this interpretation of unconditional surrender, Byrnes had confided, with an eye on popular feeling, to a colleague.

With a few prominent exceptions, the State Department duly fell into step with Byrnes’ hardline position. The perpetrators of Pearl Harbor, Bataan and innumerable atrocities were in no position to impose conditions on America. The State Department hammered out this line at a staff meeting on 7 July. Nor were there any moderate Japanese leaders, Byrnes argued; intercepts of Japanese cables revealed Tokyo’s continuing determination to fight to the bitter end.

Indeed, the six leaders of Tokyo’s dying regime had refused to surrender for fear that America would execute Hirohito, whom they revered as a living deity. The ‘Big Six’ fantasized that if they kept fighting they could cut a deal that would guarantee the life of their beloved Emperor. That was their sole remaining condition.

The Japanese leaders knew they were effectively defeated. By July 1945, Japan had no effective navy or air force (a few kamikaze planes). Most of the army was in China and Japanese-occupied Manchuria stranded and demoralized. The US Navy blockade denied the regime vital supplies of oil, coal and iron ore. Meanwhile, General Curtis LeMay’s aircraft continued firebombing Japanese cities at will; by July more than 60 were smoldering ruins, with hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties. Yet still they fought on.

Byrnes’ obsession with privacy has obscured many of his words and deeds, leading some to infer what a man of his character might have done rather than what he did, during the coming events.

The Protestant convert (he grew up a Catholic) from South Carolina has been variously described as deceitful, pathologically secretive, a master of the dark arts of political arm-twisting and openly racist.

Some of these criticisms are unfair. For instance, while Byrnes opposed the principle of racial integration – a central tenet of Roosevelt’s civil liberties program – he refused to join the Ku Klux Klan at a time when it was politically expedient to do so. He shared the Klan’s basic ideas but baulked at their methods: the lynching of black men was not the politician’s way. His restraint was thought courageous at the time because, as an ex-Catholic, he had much to prove to the hooded Klansmen who tended to persecute papists when blacks were scarce.

Whatever Byrnes’ flaws or strengths, his actions must be seen in the light of his record. He was a skilled judge and administrator, and a highly experienced politician of the kind that excelled on committees. His work as head of the Office of War Mobilization was exemplary at a time of national emergency. His deep knowledge of Washington and his thwarted ambition – he had hoped to succeed Roosevelt as president – quickly established him as Truman’s personal ‘coach’ on sensitive areas of policy.

The question of ‘unconditional surrender’ exercised Byrnes’ mind in the weeks before the Potsdam peace conference with Stalin and Churchill, America’s allies, was scheduled to begin on 16th July.

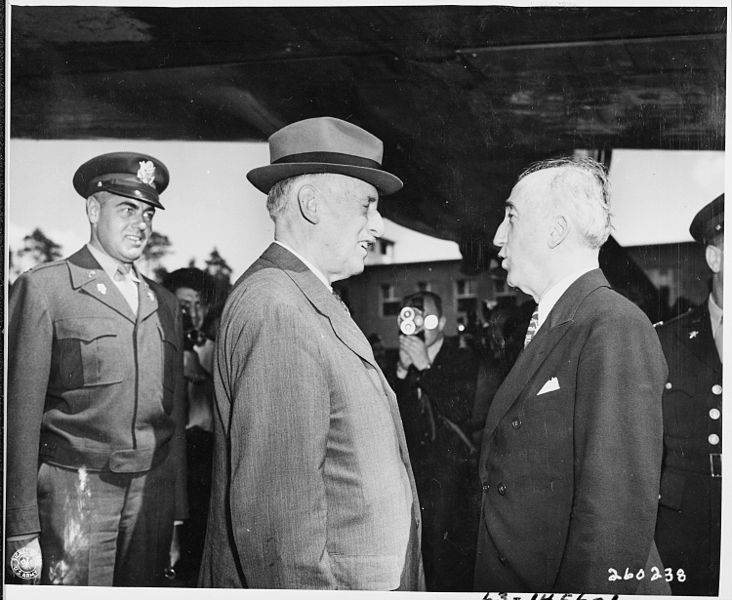

Secretary of War Henry Stimson talks with Secretary of State James Byrnes upon their arrival at Gatow Airport in Berlin, Germany for the Potsdam Conference. Image is in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

On the journey across the Atlantic, Byrnes immersed himself in the draft of the Potsdam Proclamation, the ultimatum to Japan to surrender or face ‘prompt and utter destruction’. The draft was a synthesis of the work of War Secretary Henry Stimson and Under-Secretary of State Joseph Grew, both moderates who favored softening the surrender terms to hasten the end of the war.

Byrnes fastened on to two elements of the draft: first, the authors had left open the possibility of Japan retaining a ‘constitutional monarchy’ under the present dynasty; second, it included the Soviet Union as a signatory (along with the United States, Britain and China).

Byrnes loathed the document. Any deal that retained Hirohito would outrage American public opinion, and the Soviet Union, as a co-signatory, repelled him: it would give the Soviet leader a seat at the negotiating table – with the dreadful prospect of a re-run in Asia of Russia’s east European land grab after Germany’s surrender.

At some point – it is unclear precisely when – Byrnes deleted any reference to the Emperor and struck off the Soviet Union’s name. He initialed his amended draft and wrote ‘Destroy’ beneath his initials (a copy of which survives in the Truman library). Between draft and delivery of the document, the atomic bomb would be successfully tested, on 16th July, in the New Mexico desert.

Byrnes’ editing not only gave the lie to Truman’s publicly stated aim at Potsdam to get the Soviets into the Pacific war. It would also strengthen Japan’s determination to fight on, for two reasons: it left Hirohito’s role unclear, arousing fierce opposition in Tokyo; and it suggested that the Russians were still ‘neutral’ towards Japan (under a longstanding neutrality pact between the two countries, which expired in 1946). In fact, Russia was hankering to get into the Pacific war, to reclaim the real estate lost to Japan in 1904-05.

Byrnes’ editing not only gave the lie to Truman’s publicly stated aim at Potsdam to get the Soviets into the Pacific war, but would also strengthen Japan’s determination to fight on, for two reasons: it left Hirohito’s role unclear, arousing fierce opposition in Tokyo; and it suggested that the Russians were still ‘neutral’ towards Japan (under a longstanding neutrality pact between the two countries, which expired in 1946). In fact, Russia was hankering to get into the Pacific war, to reclaim the real estate lost to Japan in 1904-05.

And so, on receipt of the Potsdam ultimatum on 28 July, the three members of Tokyo’s hardline faction pressed Prime Minister Suzuki to officially mokusatsu the document (kill it with silence):

‘The government does not think that [the Potsdam statement] has serious value. We can only ignore [mokusatsu] it. We will do our utmost to fight the war to the bitter end.’

Without a friend in the world, Tokyo waited silently to learn the full meaning of the words ‘prompt and utter destruction’.

To US dismay, neither the atomic destruction of two cities, nor the Soviet invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria, on 8th August, compelled Tokyo to surrender.

Soon after the destruction of Nagasaki, the six old Samurai who led Japan issued instructions to the country to fight on. They were prepared to fight to the last Japanese soul to protect the life of the Emperor. Governor Nagano of Nagasaki even commissioned the design of a special atomic headgear with ear flaps and a visor to protect civilians ‘from the terrific blast and high heat’ of future atomic bombs.

At the same time, Prime Minister Suzuki approached the Emperor to intervene in order to break the deadlock between the three moderates and three hardliners in cabinet, and stuck to the policy of seeking a conditional peace that preserved the Imperial system or Kokutai.

In this spirit, the regime sent another ‘peace feeler’ to the world – this one with Hirohito’s imprimatur. It pursued the same line: unless the Emperor and the Imperial System were spared, Japan would continue to fight to the last man, woman and child.

American radio picked up the message at 7.30am on 10 August. The Japanese insistence on this single condition perplexed Truman’s administration, especially Byrnes: what on earth would compel this benighted nation to surrender?

The President canvassed his colleagues’ views at a meeting that morning; should they accept the condition? Yes, said Truman’s chief of staff, Fleet Admiral William Leahy: the Emperor’s life was a minor matter compared with delaying victory. Yes, said Stimson, who argued that America needed Hirohito to pacify the scattered Imperial Army and avoid ‘a score of bloody Iwo Jimas and Okinawas’. Later Stimson gave another, more pressing reason to accept: ‘To get the [Japanese] homeland into our hands before the Russians could put in any substantial claim to occupy and rule it.’

No, said Byrnes. Instead, he rejected the consensus, seeing no reason to openly accept the Japanese demand. Why, Byrnes asked, should we offer the Japanese easier terms now the Allies possessed bigger sticks: ie, atomic bombs?

On the other hand, Byrnes had come to see the Emperor’s value in peacetime, and as a result reversed his position: the Imperial House should be allowed to exist, he now reasoned, but should be seen to exist at America’s pleasure, not at Japan’s will.

‘Ate lunch at my desk,’ Truman jotted down later, mightily pleased with Byrnes’ contribution. ‘They wanted to make a condition precedent to the surrender . . . They wanted to keep the Emperor. We told ’em we’d tell ’em how to keep him, but we’d make the terms.’

Here was Truman’s first admission of a concession over the surrender terms. The diplomatic challenge was how to frame the concession without seeming weak; in short, how to impose a ‘conditional unconditional surrender’ on Japan?

The wily Byrnes had the answer. Not for nothing had Stalin called him ‘the most honest horse thief he had ever met’. Byrnes drafted a compromise that read as an ultimatum.

In fact, the ‘Byrnes Note’ was a little masterpiece of amenable diktat: it demanded an end to the Japanese military regime while promising the people self-government; it stripped Hirohito of his powers as warlord while re-crowning him ‘peacemaker’:

‘From the moment of the surrender,’ the Byrnes Note stated, ‘the authority of the Emperor shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers . . .’ Hirohito ‘shall issue his commands to all the Japanese military, navy and air authorities and to all the forces under their control wherever located to cease active operations and to surrender their arms . . . The ultimate form of government of Japan shall . . . be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.’

The Byrnes Note clarified for the first time Hirohito’s post-war role. The Emperor and his dynasty would be allowed to live. It was unthinkable that the people’s ‘freely expressed will’ would deny their legitimacy. Washington had met Japan’s sole condition.

The Byrnes Note flashed to Tokyo, via Switzerland, and Washington awaited Tokyo’s response: ‘We are all on edge waiting for the Japs to surrender,’ Truman wrote. ‘This has been a hell of a day.’

At first, America’s compromise had the perverse effect of deepening the factional divide between the three hardliners, who refused to believe it and pledged to fight on; and the three moderates, who pressed to accept it.

Tokyo argued for three days. The Big Six vacillated over the meaning of Byrnes’ wording. Helpless to decide what to do, they appealed to Hirohito to make a second Divine Intervention. With his own life and dynasty now clearly intact, the Emperor recommended surrender.

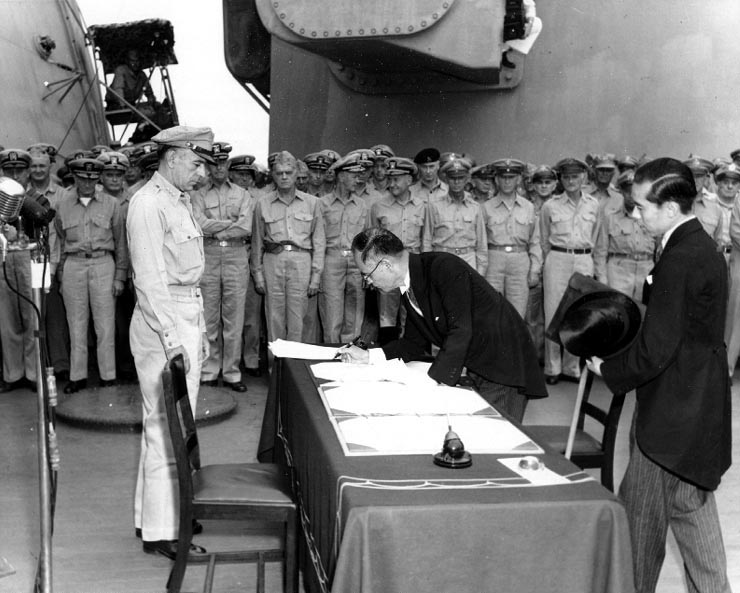

Japanese foreign affairs minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signs the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on board USS Missouri as General Richard K. Sutherland watches, September 2, 1945. Image is in the public domain, via Wikipedia.

At 11pm Tokyo telegraphed Hirohito’s acceptance of the Byrnes Note to the four Allied powers, via Switzerland and Sweden. The Emperor repaired to his office to record his famous rescript to the people.

The Byrnes Note – ie the gift of the Emperor’s life – had achieved what two atomic bombs and the Soviet invasion had so far failed to achieve: the conditional surrender of the Japanese.

PAUL HAM is an historian, specializing in twentieth-century conflict. He is the author of the highly acclaimed Kokoda. A former journalist, he has worked for the Financial Times Group and was the Australia correspondent for The Sunday Times of London for fifteen years. His latest book is Hiroshima Nagasaki.