by John Boessenecker

Extremely modest and humble, Frank Hamer left behind but scant correspondence and no diaries or journals. Even to his closest friends Frank Hamer rarely spoke of the violent events of his long career. Yet his story is not lost. It lives on in moldering court records, yellowed newspapers, obscure archives, and the forgotten memoirs of his fellow lawmen.

Frank Hamer: The Bandit war

In the blackness, he sensed death. Frank Hamer stepped cautiously along the railroad tracks, his high-heeled boots skittering on the ties and the gravel. With Captain Fox at his side, Frank Hamer approached the bullet-riddled linemen’s shack. Frank Hamer swung up the barrel of his Winchester and shoved open the door. Bursting inside, he was stopped cold by a horrendous sight. The insurgents had done their deadly work. Before him lay the body of an aged Mexican woman, weltering in her own gore. The back of her head had been blown entirely off. Beside her, clustered on the blood- drenched floor, cowered several terrified railroad hands and their wives. Never was a group of Mexicans so happy to see a Texas Ranger.

Frank Hamer had joined Company B at just the right time. Its captain, forty- eight-year-old James Monroe Fox, was a stocky, oval-faced professional lawman. He had long served as a deputy sheriff and constable in Austin, where in 1902 he shot and killed a black prisoner attempting to escape. Political connections got him appointment as a Ranger captain in 1911. Frank Hamer was active and energetic but seriously deficient in leadership. Captain Fox’s biggest problem came in the form of a notorious revolutionary leader, robber, and smuggler named Francisco “Chico” Cano. Chico Cano’s gang numbered about one hundred, formerly followers of Mexican revolutionary leader Pascual Orozco. Cano and his bandidos rustled cattle on the Mexican side and smuggled them into Texas, then stole horses in Texas and sold them in Mexico.

The Mexican Revolution had sparked unrest along the entire Rio Grande, from El Paso to the Gulf of Mexico. Its most populated region was the river’s lower reach, the Rio Grande Valley, extending inland one hundred miles from its mouth near Brownsville. The Rio Grande Valley includes Starr, Cameron, Hidalgo, and Willacy Counties. Historically the region had been an arid, chaparral-covered desert, but the introduction of large-scale irrigation in 1898, coupled with the arrival of the railroad six years later, transformed the valley into an important agricultural center. Farmers and laborers from both sides of the border flocked to the Rio Grande Valley. For several generations past, Tejanos (Mexican Americans born in Texas), who were in the majority, had lived in relative harmony with Anglos. White political bosses had the electoral support of the Spanish-speaking population. Political power was concentrated in the hands of big landowners, lawyers, and merchants.

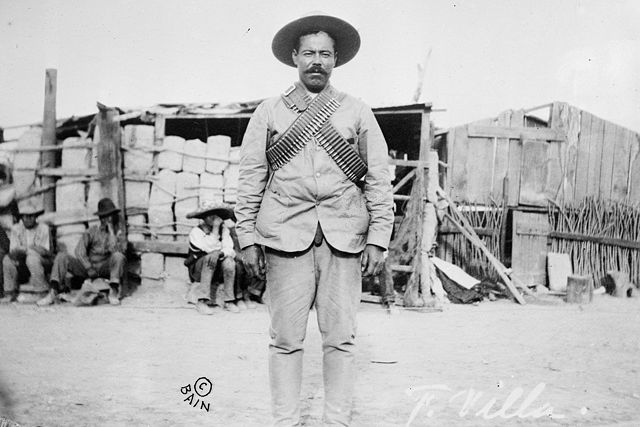

Thus began an extraordinarily confused and anarchic period of Mexican history. During the next ten years, the country would see no less than ten presidents. Francisco Madero proved a weak leader and incurred the wrath of both Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco by failing to offer them political appointments. In a bloody coup led by General Victoriano Huerta, Madero was assassinated. General Huerta served as president for one year, during which time he was violently opposed by Venustiano Carranza, a politician and rancher. In 1914 U.S. forces seized the port city of Vera Cruz, cutting off arms shipments to Huerta from Germany. After a crucial defeat by Pancho Villa two months later, Huerta resigned the presidency and went into exile. A civil war broke out as Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa, and Alvaro Obregón battled one another for control. Though Pancho Villa had been a lifelong criminal and robber, he enjoyed the most American support until he made the foolish decision to raid Lincoln, New Mexico, in 1916. President Woodrow Wilson refused to extend official recognition to any of them. Venustiano Carranza later obtained the presidency until he was finally assassinated in 1920.

Frank Hamer’s reenlistment was immediately preceded by two more events that were pivotal in the history of the Ranger force. In January of 1915 a new governor took office—James Ferguson, known as “Farmer Jim” or “Pa” Ferguson. The most corrupt Texas governor of the twentieth century, Ferguson had opposed urban Democrats and was supported by rural tenant farmers, working men, and pro-liquor forces. One of Ferguson’s first acts was his refusal to reappoint Ranger Captain John R. Hughes, the legendary “Border Boss,” and the last of the “Four Great Captains.” Although Ferguson’s stated reason was Hughes’s age— sixty—in fact he intended to pack the Rangers with political supporters. Captain Hughes’s forced retirement ended the institutional professionalism imposed by the four great captains and marked the beginning of the blackest chapter in the annals of the Texas Rangers.

The second pivotal event was one of the most infamous in Texas history—the Plan of San Diego. A radical manifesto supposedly drawn up in San Diego, seat of Duval County, it called for a full-scale race war in the Southwest. According to the plan’s exhortations, on February 20, 1915, all Mexicans were to rise up in arms against U.S. tyranny. Territory lost in the Mexican War—Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California—would be “freed” and annexed to Mexico. Every North American male over sixteen would be put to death. Six other states were to be given to blacks as an independent nation, a buffer region between Mexico and the United States. All plan members must be Hispanic, black, or Japanese, and they would carry a white battle flag with red fringe. This harebrained scheme had absolutely no chance of success. It be- came public when one of its adherents was arrested with a copy in his possession. The judge who heard the case thought he was a crackpot. But Texas lawmen took the Plan of San Diego very seriously, as did many impoverished, disaffected Hispanics in the Rio Grande Valley. They suffered from ethnic, political, and economic discrimination and were willing to join any movement that gave them hope for a better future. To disenfranchised Tejanos and Mexicans, the Plan of San Diego seemed to provide just that. Newspapers reported the details of the plot, which created panic among Anglos on the border. But February 20 came and went without any uprising, and for the next several months Anglos in the Rio Grande Valley breathed easy.

Just after Frank Hamer rejoined the Rangers, the Plan of San Diego suddenly took on new life. It came to be known as the Bandit War. In early July a band of rebels, or sediciosos (seditionists), led by Luis de la Rosa, appeared wraithlike from the rugged brush country north of Brownsville. De la Rosa was a former shopkeeper, ex–deputy sheriff, and suspected cattle thief. On July 4, 1915, his riders attacked a ranch near Raymondville, fifty miles north of Brownsville, then reportedly killed two Anglos near Lyford. They fled into the dense chaparral with posses and U.S. troops in pursuit. Three days later, the foreman of the vast King Ranch caught five members of the band with stolen cattle. They opened fire, and he shot back, killing one raider and wounding another. On July 12 the marauders robbed a store near Lyford, and five days afterward one raider killed an Anglo youth in a pasture eighteen miles east of Raymondville. On July 25 the band torched and destroyed a rail- road bridge near Sebastian. Six days later, they raided Los Indios ranch and killed a Mexican. These brazen attacks terrorized the Anglos, who demanded protection from U.S. troops and Texas Rangers.

On August 2, 1915, a band of fifty Mexican riders was spotted crossing the Rio Grande near Brownsville. Caesar Kleberg, manager of the huge King ranch, and political boss Jim Wells wired Adjutant General Henry Hutchings in Austin, urging him to come personally. Hutchings sent a telegram to Captain Fox in Marfa and ordered him to bring his entire company to Brownsville. Then Hutchings boarded a train for Brownsville, arriving on August 6. He discovered that on that very morning fifteen sediciosos, led by Luis de la Rosa, had attacked the little settlement of Sebastian, forty miles north of Brownsville. They looted the two general stores, then captured an Anglo farmer and his son and shot them to death. Before escaping, the raiders threatened to kill other prominent citizens. Reported The Dallas Morning News, “Today’s en- counter dissipated the idea that the bandits were from across the Rio Grande. Reliable Mexicans and Americans who saw them recognized several members of the band as having lived in the northern part of this county for years.”

That night, August 6, a posse led by General Hutchings and Captain Ransom shot and killed three suspected raiders on the McAllen ranch near Paso Real. Sheriff Vann, who was present, later insisted that the suspects were unarmed. The following noon, Captain Fox and seven of his Rangers, including Frank Hamer and Jim Dunaway, arrived in Brownsville by train. On the morning of August 8 they received a telephone message from Caesar Kleberg, manager of the King ranch, advising that Mexican raiders had been spotted on his range south of Kingsville. Adjutant General Hutchings quickly organized a strong posse: Captains Fox and Ransom with Frank Hamer and thirteen more Rangers, plus Corporal Allen Mercer and seven privates from Troop C, Twelfth Cavalry. They boarded a special train and headed for Norias, headquarters of the Norias division of the sprawling King ranch, the largest in Texas. A U.S. mounted immigration inspector, D. Portus Gay, lounging on the front porch of the Immigration Service office near the depot, was surprised to see the special train with a large posse aboard. Seeking excitement, he decided to head for Norias himself, and at 3:30 boarded the northbound passenger train. On the way, he picked up Deputy Sheriff Gordon Hill and two customs inspectors who were former Rangers, Pinkie Taylor and Marcus “Tiny” Hines, plus two civilian volunteers, Sam Robertson and a youth named Vinson.

Meanwhile, Frank Hamer and the rest had arrived in Norias. Situated on a flat plain seventy-five miles north of Brownsville, Norias was an isolated cattle-shipping point for the King ranch. The headquarters, a two- story wood frame house, was fifty feet west of the railroad tracks. A hundred yards south stood a railroad section house, and just across the tracks was a toolshed and a pile of cross ties. A hundred feet north of the ranch headquarters were two bunkhouses. The Rangers found Norias occupied by only a handful of people: foreman and Special Ranger Tom Tate; cowboys Frank Martin, Luke Snow, and Lauro Cavazos; the carpenter, George Forbes, and his wife; and the black cook, Albert Edmunds, and his wife. Several Mexican railroad hands and their wives, including an elderly woman, Manuela Flores, lived in quarters connected to the section house.

Tom Tate supplied the Rangers with King ranch horses. Then General Hutchings, the two captains, Frank Hamer, and the rest of the Rangers mounted up, and Tate led them toward a water hole twelve miles southwest, hoping to strike the trail of the raiders. The eight cavalrymen were left behind to guard the ranch house. At 5:30 the northbound train stopped in Norias, dropping off Portus Gay and his posse. They were invited into the ranch house to eat supper. After the meal, they stepped onto the front porch and spotted riders approaching from the east. Tiny Hines remarked, “There come the Rangers back.” But Portus Gay, squinting into the bright evening light, saw Mexican sombreros and exclaimed, “Look at those big hats and that white flag. They are damned bandits!”

Sixty bandoleer-draped riders, armed with Mauser rifles, were closing fast. Some were Carranza’s soldiers; others, Tejano adherents to the Plan of San Diego. Carrying a battle flag and commanded by Luis de la Rosa and at least one Carranza officer, they planned to wreck and rob a train at Norias. Quickly, the U.S. cavalrymen took up prone positions behind the low railroad bed, between the tracks and the house. Corporal Mercer was big and burly, but his soldiers were mere boys, most only eighteen or nineteen years old. As the raiders closed to 250 yards, the soldiers opened up with a barrage from their Springfield rifles. The guerrillas dismounted and returned the fire. Frank Martin and two of the soldiers were wounded almost immediately. The rebels charged for- ward as one band circled to the south to try to flank the defenders. Lawmen and cowboys took up positions along the tracks, while the six- foot-four, three-hundred-pound Tiny Hines, armed with a ten-gauge Winchester Model 1887 lever-action shotgun, squeezed behind a large water barrel.

The biggest battle of the Bandit War was under way. Deadly fire from the defenders forced the sediciosos to take up positions behind the railroad toolshed, the section house, and the pile of cross ties. Then they broke into the section house, where one of their leaders, Antonio Rocha, demanded that Manuela Flores tell them how many defenders were at the ranch headquarters. She answered defiantly in Spanish: “Why don’t you go over there and see, you cowardly bastard of a white burra.” Rocha jammed the muzzle of his revolver into her mouth and blew out the back of her head.

As rebels on foot and horseback fired on the defenders from two sides, the raiders in the section house rained bullets on the soldiers. The defenders, afraid of hitting railroad hands in the section house, did not fire at it. Lauro Cavazos managed to shoot the horse out from underneath one of the rebel leaders. Meanwhile, the three wounded defenders were carried into the ranch house. Several attackers got caught behind a barbed wire cattle fence east of the tracks and were shot down by the defenders. Seeing that the raiders could not get past the fence, the rest of the defenders rushed inside the ranch house and returned the fire from doors and windows. The young troopers, with only ninety rounds per man, carefully chose their targets. The black cook, Albert Edmunds, crawled out the door to a telephone hanging on an outside wall. Amidst the shattering roar of gunfire, he managed to reach Caesar Kleberg in Kingsville, told him of the raid, and begged for help. Then, braving the fire, Edmunds crawled from one defender to another, bringing each of them water. While the man was drinking, Edmunds took over his rifle and fired at the marauders.

The battle raged for more than two hours. The defenders were almost out of ammunition, and it appeared that they would be overwhelmed. Just at dark, about 8:30, the raiders mounted a final charge, “shooting and yelling like Indians,” as Portus Gay recalled. At a range of forty yards, Pinkie Taylor shot and killed the leader, and the attack faltered. The raiders, who had only expected to encounter a few cowboys, lost heart in the gathering darkness. The rebels loaded their wounded onto horses and rode off in the blackness, shouting, “Gringos cabrones!” Portus Gay later said that they had wounded half the raiders, some of whom had to be tied to their saddles. The defenders, believing that the fighters in the toolshed and section house had stayed behind, held their positions.

An hour later, Frank Hamer and the rest of the Rangers, oblivious to the battle, returned to Norias. The defenders first thought the approach- ing horsemen were raiders, until Lauro Cavazos recognized Tom Tate’s voice. They yelled at the Rangers to “fall off ” their horses “as Mexicans had the house surrounded.” Frank Hamer and Captain Fox quickly ran up the tracks and approached the two outbuildings. Fox later recalled, “In a dark room of one shack we stumbled over the body of a dead Mexican woman, and in the road outside we found a horribly wounded Mexican man.” Next to the corpse of Manuela Flores they found several terrified section hands and their wives huddled together. The Rangers returned to the ranch house, where they were both embarrassed and chagrined to learn how narrowly they had missed the marauders. The loudmouthed Captain Ransom began to lecture the defenders on how they should have conducted the battle. At that, Pinkie Taylor exploded: “Listen—we were here—we did not get a man killed—we were here when they came, we were here when they left, and we are still here, and I don’t know what you all would have done if you had been here, but I do know there was not a goddamn son of a bitch of you here!”

Deputy Sheriff Gordon Hill was just as angry. He barked at the Rangers, “If you all are such hell-roaring fighters, why don’t you go after them? They can’t be so very far away, as they have not been gone very long.” But General Hutchings and Captains Fox and Ransom, concerned about an ambush in the dark, prudently elected to delay pursuit until morning.

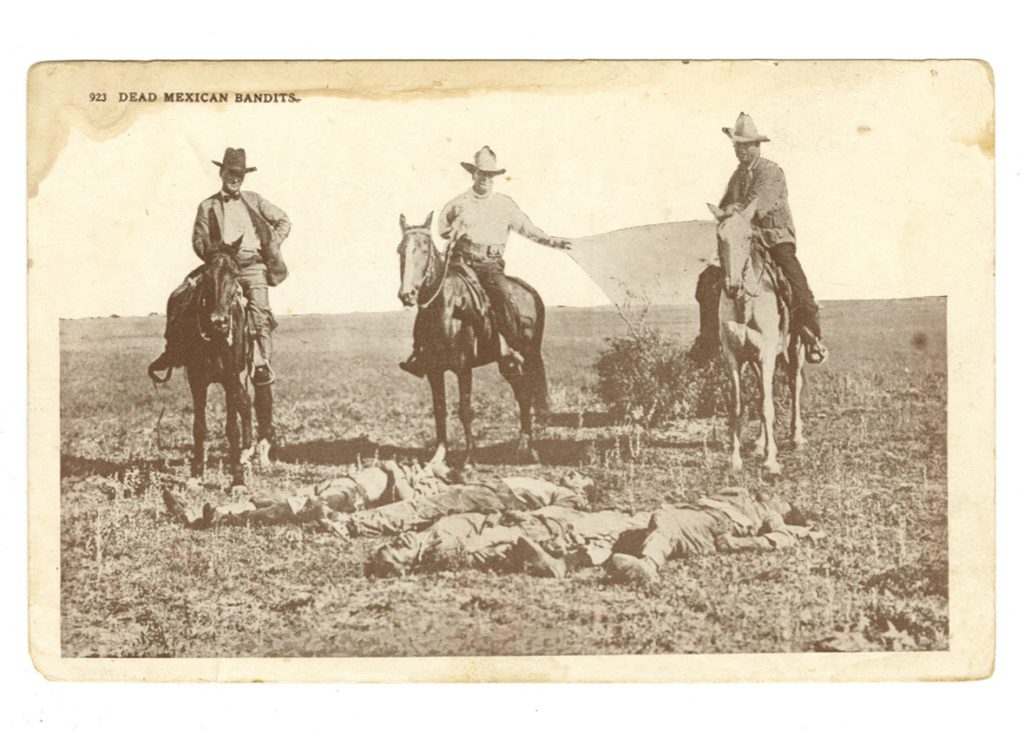

The Rangers found four bodies on the plains east of the ranch house. Nearby, they discovered a white battle flag emblazoned with a large letter E. The badly wounded raider gave his name as Jose Garcia and said he was from San Benito, Texas. He claimed, improbably, that he had been forced to join the attackers and admitted that their goal was to reclaim the Rio Grande Valley for Mexico. Recalled Portus Gay, “Just after making this statement, he died. I will not state just how or why he died.” The obvious inference was that one of the posse murdered him. Gordon Hill’s father, Lon, who arrived on a special train with Sheriff Vann soon after the battle ended, also talked with Garcia, who told him, “Now, you all will kill me, and I want you to tell my folks that I am killed.” Based on these accounts, Jose Garcia is often considered to have been murdered by Texas Rangers. However, contemporary wire service reports differ. They identified the captured man as Jesus Garcia of Brownsville and said he died the following day from his battle wounds.16 In the morning, a northbound train rolled in. On board was Robert Runyon, an energetic and enterprising photographer from Brownsville who had created a cottage industry photographing scenes from the Mexican Revolution—many of them morbid images of dead bodies— and selling them as real-photo postcards, which were distributed widely in the United States and Mexico. Now, Runyon unlimbered his heavy camera and took numerous photos, including the Norias ranch head- quarters and the six uninjured troopers standing on the front porch. He then carried his camera to the spot where the dead bodies lay in preparation for burial and made several exposures of the corpses. He took two images of Frank Hamer and another posseman, who appears to be Jim Dunaway, posing on horseback behind the dead bodies and holding the captured battle flag between them. In the photos, Frank Hamer is slouched easily on his horse, wearing a baggy canvas brush jacket with a U.S. Army–issue canvas cartridge belt slung across his chest. Runyon also took several photographs of Captain Fox, Tom Tate, and other lawmen with their lariats tied around three dead bodies as they prepared to drag them across the prairie.

In accordance with the jingoistic ethos of that era, the Rangers posed proudly. The dead Mexicans were blood relics, trophies of war, representing triumph in battle. Ironically, the Rangers had nothing to do with killing the raiders. According to Lauro Cavazos, he and another King Ranch cowboy came up with the idea of dragging the bodies to a nearby sandbank, where they could easily be interred in a mass grave. After posing for the images, the Rangers prepared to bury the bodies. One of them intoned over the grave, “Dust to dust, if the cabrones don’t kill you, the Rangers must.”

John Boessenecker, author of TEXAS RANGER: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, the Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde, a San Francisco trial lawyer and former police officer, is considered one of the leading authorities on crime and law enforcement in the Old West. He is the award-winning author of eight books, including Bandido: The Life and Times of Tiburcio Vasquez and When Law Was in the Holster: The Frontier Life of Bob Paul. In 2011 and 2013, True West magazine named Boessenecker Best Nonfiction Writer. He has appeared frequently as a historical commentator on PBS, The History Channel, A&E, and other networks.