by Robert Klara

One of the reasons why we know so much about the perilous and sinister world of Hitler’s hierarchy is because so many of its members spent time documenting it. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels kept a diary during the war years, as did Reich minister for occupied eastern territories Alfred Rosenberg, who presided over the implementation of the Holocaust. Goebbels committed suicide and Rosenberg swung in the Nuremberg Gaol, but Minister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer, finding himself in Spandau Prison after the war to serve a 20-year sentence, spent those two decades secretly penning his memoir.

We have portraits of Hitler from military men such as Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, from administrators like chief of staff Otto Wagener, and from confidantes such as Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl. And thanks to the published memoir of Christa Schroeder, Rochus Misch, Heinrich Hoffman, and Heinz Linge, we know what it was like—respectively—to type letters for Hitler, guard Hitler, photograph Hitler, and dress Hitler.

There is one more account that deserves a place on this list. It is that of Erich Kempka, whose memoir appeared as recently as 2010. At 105 pages, the edition is brief. Nevertheless, it is a key to the understanding of Hitler and his realm:

Kempka remembers what it was like to drive Hitler around in a car.

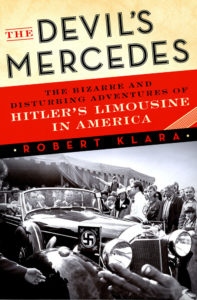

Why should that matter? To me, at least, it mattered a great deal. My most recent book, The Devil’s Mercedes, tells the story of how two Mercedes-Benz limousines believed to have belonged to Adolph Hitler mysteriously appeared in the United States in the years after the war. More precisely, it tells the story of how Americans responded to the presence of these cars on their soil. Stripped of their original purpose as transportation, the cars, once they arrived in America, underwent a curious metamorphosis. They became not only symbols of the fallen Reich, but surrogates for Hitler himself—which explains why the vehicles drew countless thousands of spectators, then proceeded to agitate, disgust, and enrage them all.

But all of that would come later, after the guns fell silent. My interest in Erich Kempka stemmed not just from the need to document the original, functional purpose to which the Nazi limousines were put, but the desire to access and understand the curious and telling dynamic fostered by automobiles. For better or worse, the cars we drive say much about us. They speak to our egos as well as our insecurities. As it would turn out, Hitler was no exception to this standard, and Kempka’s memoir illustrates as much.

The son of a miner, Erich Kempka was born in Oberhausen in 1910. As a youth he worked for an automobile distributor before the Gauleiter of Essen took him on as a driver, then opened up a series of doors through which Kempka quickly passed until he found himself in the center of things. By 1932, Kempka—at 22 years of age—was driving Hitler around Germany.

Though Hitler was a year from the chancellorship at that point, his status as leader of the National Socialist Party had already put fine motorcars at his disposal. Invariably, they wore the Mercedes-Benz star atop their grilles. Hitler had been an avid proponent of Mercedes since the days of the Munich Beer Hall Putsch, and he had insisted on the marque after a truck hit his Mercedes in 1930, leaving him without a scratch. Mercedes also won Hitler’s admiration because the cars seemed to confirm Hitler’s own notions of German superiority. In Speer’s account of the Reich, Hitler brags about his Mercedes’ ability to bully an American car off the road. “Our supercharger is good for over a hundred,” said Hitler. “Those Americans are junk compared to a Mercedes.”

Erich Kempka’s memories of driving with Hitler reveal a side of him that can be difficult to manage: The 20th century’s most efficient mass murderer could—under the right circumstances—show a human side. Shuttling among his many speaking engagements, Hitler eschewed the Mercedes’s cushy rear compartment in favor of sitting up front with his driver, talking for hours and doing the navigating with a road map folded across his lap. Hitler prepared box lunches for his chauffeur and assured that he had a proper bed to sleep in. “My drivers,” Hitler said, “are my best friends.”

That his drivers, however, were also little more than street thugs in tailored SS uniforms revealed the nature of that friendship. After all, a criminal can always find a ready sympathizer in another criminal.

The experiences of candidate Hitler on the road also illustrate his social awkwardness and hypocrisy. Despite fashioning himself as a world leader, Hitler seemed more at ease in a car talking to his driver than he did in most formal settings. And, despite Hitler’s own well-publicized moralizing, he apparently looked the other way when his carousing driver wound up with one fräulein or another for a roll in the hay. “A good sex life relaxes chauffeurs,” proclaimed Hitler (though it was the late American journalist James P. O’Donnell, not Erich Kempka, who reported that quote).

Hitler’s ascent to the Chancellorship in 1933 eliminated all concerns of the purse, and soon Erich Kempka was driving Mercedes’ top-of-the-line model, the Grosser 770K. It was an opulent, monstrous automobile whose sinuous lines and massive bulk was as much a manifestation of Hitler’s warped sense of grandiosity as it was a means of transportation. Hitler relished in motoring around in the titanic limousines, and enjoyed just as much that he power allowed him to hand them out as gifts of state. “Hitler required me to keep him permanently informed about the progress of these cars at the works,” Kempka recalled, “just as he interested himself especially in all technical matters and innovations.”

In time, those innovations at the Mercedes-Benz plant outside of Stuttgart would become a kind of testimony to the derision that Hitler bred, as well. Much has been said about Hitler’s penchant for riding in motorcades while standing up, his body in full view of a potential sniper. Hitler insisted that he had nothing to fear from the German volk—at least, he did until a failed assassination attempt in 1936 changed his mind. Hitler had missed the explosion of a planted bomb by a mere 12 minutes. It was at that point that he began riding in 770Ks that Mercedes had fitted with armoring and bulletproof glass. Kempka vividly recalls Hitler’s satisfied inspection of the armored limousine in Berlin, and his subsequent declaration that “in the future, I will use only this car, for I can never know when some idiot might throw another bomb in front of my vehicle.

Erich Kempka may have taken pains to stress the humanity of his boss, yet in the process he had also (probably without realizing it) revealed Hitler’s arrogance, ignorance, and paranoia—all seen, as it were, through an automotive windshield. What’s more, a measure of poetic justice lurks at the end of Kempka’s account: the story of how Hitler’s limousines, the consummate symbols of his wealth and power, would also be present for his demise.

Fifty-five feet below the Reich Chancellery, Hitler shot himself in the head on April 30, 1945. Amid the vicious shelling of Berlin by the Soviets, Kempka hunkered in his subterranean garage nearby, surveying the wreck of his limousine fleet—60 cars crushed by the weight of a collapsed concrete ceiling. When the telephone rang, at first Kempka did not understand the call demanding he bring 50 gallons of gasoline over to Hitler’s bunker. When he arrived and learned of der Führer’s death, the order made sense. After helping to carry the bodies of Hitler and his mistress Eva Braun (who had taken her own life along with him) up the exit stairway to the garden, Kempka hurled his boss’ remains into a shell crater.

“He lay there wrapped in the gray blanket, legs toward the bunker stairway … his right foot turned inwards,” Kempka recalled. “I had often seen his foot in this position when he had nodded off beside me on long car drives.”

Erich Kempka soaked the body and dropped a lit rag atop the dead bedlamite who’d burned the world, having dispatched his last order. The gasoline he’d brought with him had come from the Mercedes-Benzes: Kempka had siphoned Hitler’s funeral pyre directly from their tanks.

ROBERT KLARA is the author of FDR’s Funeral Train and The Hidden White House. Hailed as “a major new contribution to U.S. history” by Douglas Brinkley, Klara’s first book earned a starred review from Kirkus. Klara’s articles and essays have appeared in The New York Times, American Heritage, and The Guardian, among numerous other publications. Klara has also worked as a staff editor for magazines including Town & Country, Architecture, and Adweek. He lives in Brooklyn.