by Michael E. Haskew

The marshaling and training of the Allied forces that were to strike Hitler’s Fortress Europe on D-Day were collectively a massive undertaking. Airborne exercises took place throughout the winter and spring of 1943–44, including night jumps, since the operation was to take place in darkness roughly five hours ahead of the scheduled amphibious landings in Normandy.

Exercise Eagle, conducted on May 11–12, was intended as a dress rehearsal for the bulk of the troop carrier groups and both airborne divisions. The results of Eagle and follow-on exercises that extended to the end of the month were encouraging, although a number of the troop carrier pilots had never flown combat missions or had limited experience.

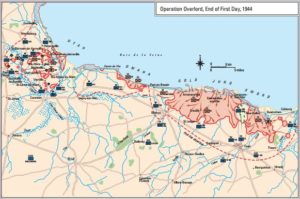

The lessons gleaned in the Mediterranean shaped the flight paths of the troop carrier serials to avoid German antiaircraft fire and minimize the possibility of potential friendly fire incidents. The preliminary flight plan was approved in mid April; however, intelligence reports necessitated significant changes. The primary German field opposition to the American airborne assault was expected to come from the 709th Infantry Division, the 91st Airlanding Division, the 1057th Grenadier Division, and the 6th Parachute Regiment.

At the end of May, elements of the 91st Airlanding Division were detected perilously close to the drop zones of both the 101st and 82nd Divisions. The 82nd drop zones were pulled eastward, and Ste. Mere-Eglise, originally an objective assigned to the 101st, was switched to the 82nd.

The changes in drop zones required alterations to the flight plans. From various airfields around southern England, the first transports would rise into the night sky shortly after midnight on June 5. Flying a generally southern course, they were to proceed to a point over the open sea, execute a 90-degree left turn, and then fly 54 miles (87km) while passing between the Channel Islands of Alderney and Guernsey.

Along the west coast of the Cotentin Peninsula at the Initial Point, code-named Peoria, the troop carriers with the 82nd aboard would proceed straight to their drop zones 11 miles (18km) inland just north of the village of La Haye. The C-47s carrying the 101st were to make a slight left turn at Peoria and reach the drop zones 25 miles (40km) away.

Along the way, the transport planes would be aided by navigational beacons and the Rebecca Eureka transponding radar system. Pathfinders would go in first and illuminate the drop zones. Once their drops were completed, the empty aircraft were instructed to turn and follow a reciprocal course back to their bases in England.

Commander-in-Chief

Senior Allied commanders acknowledged that the entire invasion plan was incredibly risky. At worst, failure meant losing the war. At best, it meant months—possibly years—of recovery in order to try again. The airborne phase was particularly worrisome. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, senior commander at SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force), shouldered the ultimate responsibility for the success or failure of Operation Overlord.

Eisenhower accepted his role and wrote a brief statement that, in the event of the unthinkable, was to be released to the media. It concluded with the frank statement, “If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

Amid the ongoing risk assessment, the airborne phase of Overlord came under increasing scrutiny. Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, commander of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force for the invasion, was pessimistic about its chances for success. Casualties were expected to run high: Some estimates concluded that half the planes carrying American paratroopers and 70 percent of the gliders would be shot down by German antiaircraft fire. Leigh-Mallory urged in writing that the American airborne plan should be scrapped.

Eisenhower weighed his options and decided that the effort should proceed; the airborne decision was just one of many that he wrestled with, taking advice from other members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff right up to the scheduled hour of departure.

When the worst weather in the English Channel in 50 years threatened to disrupt Operation Overlord, Eisenhower ordered a postponement from June 5 to the following day. According to a team of meteorologists headed by Group Captain James Martin Stagg, a narrow window of opportunity existed on June 6. The next available date with appropriate atmospheric conditions was two weeks later, June 19, and recalling the warships and vessels already loaded with troops while maintaining secrecy seemed impossible.

During a meeting at Southwick House just north of Portsmouth, England, in the early morning hours of June 5, Eisenhower asked the opinion of each of his lieutenants as to whether the invasion should proceed. When the last had expressed his thoughts, the commander-in-chief declared, “Okay, we’ll go!”

Eisenhower cared deeply about the men he was sending into battle and knew that many of them would be killed or wounded. He initially intended to visit units of the 82nd Airborne on the eve of D-Day, but Generals Ridgway and Gavin asked him to stay away, saying their troops would be distracted. Instead, the commander-in-chief traveled from SHAEF headquarters to Newbury and visited with troopers of the 502nd PIR at Greenham Common Airfield.

Eisenhower cared deeply about the men he was sending into battle and knew that many of them would be killed or wounded. He initially intended to visit units of the 82nd Airborne on the eve of D-Day, but Generals Ridgway and Gavin asked him to stay away, saying their troops would be distracted. Instead, the commander-in-chief traveled from SHAEF headquarters to Newbury and visited with troopers of the 502nd PIR at Greenham Common Airfield.

Laughing and joking with the paratroopers, he asked one of them where he was from. The trooper replied, “Michigan.” Eisenhower beamed and replied, “Oh yes! Michigan—great fishing there—been there several times and like it.”

Captain Harry Butcher, Eisenhower’s naval liaison officer and a close friend, remembered, “We saw hundreds of paratroopers with blackened and grotesque faces, packing up for the big hop and jump. Ike wandered through them, stepping over packs, guns, and a variety of equipment such as only paratroop people can devise, chinning with this and that one. All were put at ease. He was promised a job after the war by a Texan who said he roped, not dallied, his cows, and at least there was enough to eat in the work.”

When Eisenhower wrote his memoir of the war, Crusade In Europe, he recalled the evening. “I found the men in fine fettle, many of them joshingly admonishing me that I had no cause for worry, since the 101st was on the job, and everything would be taken care of in fine shape. I stayed with them until the last of them were in the air, somewhere about midnight. After a two hour trip back to my own camp, I had only a short time to wait until the first news should come in.”

Airborne Insertion

The airlift missions for the 101st and 82nd Divisions were code-named Albany and Boston respectively and included the 432 planes carrying the 101st and the 369 transporting the 82nd. The planes were further divided into serials of primarily 36 or 45 planes. Formations remained tight as the aircraft made landfall. However, cloud cover, strong winds, and increasingly heavy flak caused them to loosen substantially.

While some troop carrier groups placed the majority of their sticks on or near the drop zones, others were widely dispersed. The second flight in the second serial of the 436th Group, for example, dropped elements of the 377th Parachute Field Artillery five to seven miles (8–11km) northwest of their assigned drop zone. Among the planes carrying 82nd Airborne troopers, 118 sticks were intended for Drop Zone O.

Of these, 31 came down within or close to the zone, while 29 more landed within a mile (1.6km), 20 within two miles (3km), 17 approximately five miles (8km) distant, three at least 14 miles (22km) to the north, and some were missing. Equipment was lost or damaged, some bundles sinking to the bottom of the flooded marshes.

One entire stick of paratroopers from Company A, 502nd PIR, was dropped into the English Channel and drowned. Others actually came down on Utah Beach or in the surf, shedding heavy equipment packs and swimming or wading to the shore. Some troopers came down in flooded areas and struggled with parachutes and gear in water over their heads.

Father Francis Sampson, regimental chaplain of the 501st PIR, came to earth in deep water and cut his equipment away before his parachute dragged him to a shallow spot. Ten minutes later, he swam back to his original drop point and made several dives to locate his Communion set.

forces on June 6, 1944, included landing more than 130,000 men by sea and a further 24,000 by air.

Radioman Hugh Pritchard came down with 140 pounds (63kg) of equipment and his radio in a leg bag. He went straight to the bottom of a marsh and was then dragged some distance by his billowing parachute. Only the collapse of the parachute saved him from drowning.

Fifty-one gliders assigned to the 101st were to land in darkness on the morning of D-Day, and Brigadier General Don F. Pratt, assistant commander of the division, was killed when his glider crashed.

Troopers of the 101st groped in the darkness individually or in small groups, click-clacking dimestore “cricket” toys that were distributed to the men for recognition purposes. The 82nd had declined to use the crickets and instead relied on the recognition sign “Flash,” and the appropriate response, “Thunder.”

General Taylor searched for half an hour before finding any of his fellow paratroopers. He stumbled across a lone private, and the two embraced with relief. Riding in with the 505th PIR, General Ridgway was making his fifth parachute jump, actually qualifying for his silver wings. General Gavin, accompanying the 508th PIR, came down in an apple orchard about two miles (3km) from his drop zone, with no idea where he was. It took him an hour to become oriented.

MICHAEL E. HASKEW is the editor of WWII History Magazine and the former editor of World War II Magazine. He is the author of a number of books, including The Sniper at War, Order of Battle, and The Marines in World War II. Haskew is also the editor of The World War II Desk Reference for the Eisenhower Center for American Studies. He lives in Hixson, Tennessee.