By Don Malarkey

Easy Company After D-Day

Normandy, France, was beauty and the beast. The sprinkling of land unspoiled by war was the beauty. We, the soldiers, were the beasts. I’d see miles and miles of fields and orchards that, in places, reminded me of spots I’d seen in the Willamette Valley while hitchhiking from Astoria to Eugene back in Oregon. Then, suddenly, I’d see the remains of a horse splattered by artillery, the legs here, the head there. In some places, a breeze would bring the smell of grass and trees; in others, the rancid odor of death. Germans. Americans. Civilians. Animals. Whatever got in the way of war. One of the biggest problems we were having was taking care of our dead—getting them buried. Some of our Graves Registration guys resorted to getting drunk to do their jobs.

In the States, just as we were all coming of age and getting comfortable with school, girlfriends, jobs, along came a war. In France, just when we were all getting comfortable with war, along came reminders of home. Truth is that, lately, we hadn’t been able to get comfortable with either.

Pvt. Alton More came to me a few days after D-day—we were waiting for orders—and suggested we go into Ste.-MèreÉglise. More was a rugged John Wayne type, the son of a saloonkeeper in Casper, Wyoming. He had married his high school sweetheart, and their first child was born soon after we’d arrived in England.

“Malark, I hear there’s a pile of musette bags full of chocolate bars just waiting for a couple a guys like you and me to save from melting.”

Frankly, there wasn’t much chance of chocolate melting; Normandy was unseasonably cold and wet, for summer. The mosquitoes were thicker’n anything I’d seen in Oregon, where they can be plenty bad. And I was uneasy when I heard the bags had belonged to our soldiers who’d been killed. But we were bored and headed into town, the first liberated French village. We found the rumored bags in a vacant lot and emptied them upside down, looking for candy bars, rations, money, whatever.

Suddenly, More dropped to his knees and, in a voice almost inaudible, said, “We gotta get the hell out of here, Malark.” I looked over at him. He had broken down and was crying. Then I looked at the musette bag he’d just opened. Inside were a knitted pair of pink baby bootees. Not another word was said. We put the stuff back and left. Humbled. And, I think, a tad ashamed at the disrespect we’d shown to our fallen comrades.

Near Carentan, a town of about four thousand people, E Company was hunkered down, prepping for a final assault to capture it. Carentan lay astride the main road running to Cherbourg at the tip of the Cotentin Peninsula. The Germans wanted to keep the town; we needed it to bridge incoming troops from Omaha Beach and Utah Beach, north and south. We were camped on a roadway leading to the Douve River estuary when, about 2:00 a.m., a terrifying siren screamed in the sky. I buried my head in a roadside ditch, thinking whatever it was, it was headed straight for me. The sound faded in a few seconds. But it came back, and this time I stood and watched. It was a Stuka divebomber strafing Carentan. I never saw another one the rest of the war, and I’m convinced that, as a psychological weapon, it did the trick. I reminded myself, Never relax, Malarkey.

The next morning, we were sent to the west side of Carentan. Winters had made me mortar sergeant of the 2nd Platoon. Compton was the platoon leader. We reached an orchard. Buck sent me up a tree to see if I could give sighting instructions on a machine gun unleashing harassing fire through the attack zone.

Ah, yes, Bomba the Jungle Boy back in action. I headed up the apple tree—far easier than the firs and hemlocks of Astoria—and turned around to give a sighting to the gunner.

Suddenly, as I looked down, my legs went wobbly. I grabbed the tree in a death grip, fearing I would fall. Slowly—and trying to hide my fear from the other guys—I slid down the limbs and trunk. Goodness, if I suddenly had a fear of heights, how was I going to handle our next jump?

On June 12, on the edge of Carentan, the 506th’s 2nd Battalion, of which the 2nd Platoon was part, was walking down a road, readying for our all-important attack. It was dawn. F Company was on our left flank, D Company in reserve. Suddenly, all hell broke loose. One or two German troopers came out in the middle of the intersection, pouring machine-gun fire up and down the road. Mortar fire joined the barrage. So did tanks. They virtually stripped the hedgerow and we clung to the earth, cussing and praying in equal measure. The enemy fire split our platoon; the Germans were in a perfect position to wipe out not only our platoon, but the entire company. We scrambled to the ditches along the road, next to hedgerows, so panicked we were all but digging foxholes with our fingers. You had the feeling if you popped your head up, it’d soon be gone. It was almost as if the Germans were mowing down that entire hedgerow to get to us. It was the heaviest fire I would ever experience in war. Period.

“Move out!” Winters yelled.

Nobody moved, as if pinned in the ditches.

“I said, ‘Move it!’ Let’s go!”

Still, nobody went.

Finally, Winters got hotter than I’ve ever seen him, and we got the idea: We reluctantly headed forward—early-game nerves, I suppose. When someone tossed a grenade to take care of the machine-gun nest, we had the intersection under control. The Germans withdrew. Knowing our positions, though, they rained mortar fire and machine-gun fire on us from afar. Guys around me were going down right and left. Winters took a hit in the lower leg.

It had been a fast and furious attack. At the end, amid moans of wounded soldiers and occasional shots, I heard the oddest thing: “Hail Mary, mother of Jesus, full of grace . . .” Over and over. Not the panicked voice of a wounded soldier, but the stoic, almost calm voice of someone else. “Hail Mary, mother of Jesus, full of grace . . .” I glanced up and there was Father John Maloney, holding a small cross in his hands and walking down the center of the road, administering last rites to our dying. Never seen anything like it, a priest administering last rites with bullets bouncing around his feet. Takes a hell of a lot of conviction, and faith, for a man to do that.

Later, he’d be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his courage under fire.

Throughout the night, the Germans fired occasional shots. Were they going to mount a full-fledged counterattack at night? Needless to say, few of us slept well. What made it worse was Floyd Talbert getting gored by one of his own guys. He’d gently tapped another soldier to wake him, and the guy had, in a panic, turned and bayoneted Talbert. We weren’t sure he’d make it, but he survived.

At dawn, we readied for what we hoped would be a final attack to drive the Germans from the outskirts of Carentan. Winters would later call it the “tightest spot” Easy Company found itself in during the war, though I thought plenty of others qualified.

We rained down everything we had on the Germans; they did the same to us. At some point, E Company was the only force holding the line; units on either side had fallen back under fire, leaving us out there like sitting ducks. We had a flooded area to our right flank, and nobody on our left.

“Malark, get over here!” It was Buck Compton, whom I’d one day count as one of my closest friends, but, for now, I wasn’t sure I wanted to hear from. “We need machine-gun ammo,” he said. “You’re elected.”

My job, whether I chose to accept or not, was to scramble back to a farm building a few hundred yards away, across a pasture, near the intersection, where we’d deposited some ammo. I took off. Mortar fire rained down around me. I dove on my face and put my hands on my helmet. Blam!

Shrapnel ripped into my right hand. The mortar fire stopped. I popped up and ran harder.

Go! Go! Go! I could see the building. Fifty yards. Twenty-five. Ten. I burst in the door, breathing hard. Our medic, Eugene Roe, was up to his elbows in blood, patching soldiers right and left. By now, he was already a seasoned veteran with the wounded, able to patch and diagnose in a quiet, methodical way.

“That’s a Purple Heart wound, Malark,” he calmly said, hardly looking up from wrapping a bandage around the chest of some soldier naked from the waist up. I looked around the room. The waiting line was long and full of soldiers far bloodier than me. I mentally gulped, never having seen the wounded congregated like this in one place.

“I don’t want any Purple Hearts,” I said. “But how about a bandage?”

He patched me up. I grabbed the ammo. And praying most of the way, I made it back to the hedgerows.

I refused a Purple Heart award because, in relation to what other guys were going through, it seemed like an incidental wound. As I later wrote to Bernice, “I refused it at the time for my wound was not bad enough that it was necessary that I be decorated. Death and mangled bodies are so prevalent I felt I didn’t deserve it.”

We had ten casualties in the June 12 attack on Carentan; nine the next day in the defense of Carentan. As that defense continued, we were giving up ground fast. The Germans were relentless. We were close to being overrun. Tired. Losing guys. And hope. But at midafternoon, the 2nd Armored Division—sixty tanks strong, plus fresh soldiers—arrived to relieve us. What a wonderful sight. Much better than when Sgt. Leo Boyle had earlier stood up and seen what he thought was a line of American tanks on the horizon. “Tanks! And they’re ours!” he yelled. He was wrong. They were Germans. And he paid the price when, shortly after his pronouncement, a bullet riddled his leg. He was hit bad. And wound up being shipped back to England. It wasn’t easy seeing your buddies go down around you. Beyond losing them, you wondered the inevitable: Am I next?

After the battle, Winters came across a German soldier who was terribly wounded and crying for help. He asked me to put the man out of his misery. I obeyed my order.

That night, over K rations in a gutted church, a story was told about Ronald Speirs, a first lieutenant in D Company, giving cigarettes to a bunch of German POWs a few days before and then mowing them down. That’s nothing, someone said, Speirs had also gunned down one of his own men for disobeying him. Seems he had ordered one of his sergeants to attack directly across an open meadow at a cluster of farm buildings occupied by German machine gunners and a few tanks. Instead, the sergeant suggested he work up along a hedgerow instead of crossing in the open. Lieutenant Speirs took that as refusing a direct order, pulled his gun, and killed the man. There was no shortage of calvados and cognac in Normandy, and rumor had it that the sergeant had been drinking. In any case, the incident was reviewed by regimental commanders and Speirs was cleared of any misconduct. Still, I made a mental note: Don’t wind up with this guy as your platoon leader.

The 506th moved to a defensive position southwest of Carentan. On the second day we were there, an American soldier was coming down the hedgerow asking for me or Skip Muck. I looked up from my foxhole. There stood Fritz Niland, the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment guy whom we’d last seen at the pub in England when he was with his brother, Bob.

“How the hell are you, Fritz?”

He seemed distracted. “Seen Skip?” he asked.

“He’s in the First Platoon, just about a hundred yards down the line,” I said, remembering that the two were friends from back home in New York. Soon, Fritz came back and said good-bye to me, saying he was headed home, though he didn’t say why.

Later, Skip told me, his usual impish smile gone and his face almost in a daze, “Yesterday Fritz learned his brother Bob, who’s in the Eighty-second, had been killed on D-day.”

Bob’s platoon had been surrounded and he volunteered to man a machine gun for harassing fire while others broke through the encirclement. He used up several boxes of ammo and was cradling the gun to move to another spot when he was shot and killed with a single bullet. I remembered his prophetic words in London: “If you want to be a hero, the Germans will make one out of you—dead.”

But the rest of the story was even more chilling. “So anyway,” continued Skip, “Fritz hears this news and leaves the Eighty-second to tell another brother, Edward, a platoon leader in the Fourth Infantry Division, about Bob, only to find Edward has been killed.”

“My God,” I said.

“There’s more, Malark. By this time, Father Francis Sampson is looking for Fritz. Why? To tell him thatanother brother, Preston, a flier in the China-Burma-India theater, had been killed this week, too.”

“So, Fritz—”

“Is the only survivor of four Niland brothers serving their country. He’s being sent home ASAP.”

I instantly thought of Grandmother Malarkey, who’d lost two sons in one war and never gotten over it. “My God,” I said. “That poor mother.”

The Niland news numbed me. I had to get back from this war. Alive. If for nobody else, for Grandmother Malarkey, by then seventy years old and worried sick that she might lose a third boy to war.* (* This incident, after being told by me to Stephen Ambrose in a 1991 interview, became the basis for the movie Saving Private Ryan. Lieutenant Winters has confirmed as much in a letter.)

***

Dick Winters needed a volunteer to take out a high-noon patrol. Finding none, he came down the hedgerow to me.

“Malarkey, you’re nominated,” he said. “Report with Rod Bain, and six others, at battalion headquarters by eleven hundred.”

His statement was punctuated by the ka-boomb of some incoming shells; we were well protected in foxholes, but the incoming and outgoing “mail” kept the ground shaking frequently.

When we arrived at headquarters, we found that the patrol was a command performance by Lewis Nixon, Winters’s close pal and the resident lush. Nobody could quite figure out why those guys were such close friends; Nixon was a fullblown alcoholic and Winters didn’t drink at all. Anyway, Nixon had picked out a complex of farm buildings, about a mile in front of our positions. He wanted us to penetrate to the outbuildings or as close as we could get.

Joe Toye wouldn’t be on this team; he had been sent back to England because the medics were worried about gangrene setting in from the skin being ripped from his arm during the jump. Bain was an automatic pick because of his radio and skills with it. I also picked John Sheehy, Dick Davenport, Ed Joint, Allen Vest, and two others; eight altogether. Hedgerows would provide good concealment. We moved out and soon saw one that ran straight toward the objective. We followed it for a while.

“Sheehy,” I whispered loudly from a crouched position about six yards behind him. “Stop at the next hedgerow and the two of us will check out the lay of the land.” Staying low, moving carefully, I went to join him.

Snap. I’d stepped on a twig. In an instant, a German helmet popped up out of the hedgerow not ten feet from us, though the soldier inside was looking off to the side, not right at us. I pulled up my tommy gun, bumping Sheehy. The German soldier spun. It didn’t matter. John got him in the head with a full blast. The kraut dropped with an eerie gurgle.

In the distance, I saw other Germans, responding to the gunfire. We’re in deep trouble, I thought. “Let’s get the hell out of here,” I said. And we did. We all darted back the way we’d come. Bain had it worse than the rest, having to haul that sixty-pound radio. Winters, after we’d reported back, realized the Jerries were thicker than he thought. “No more day patrols,” he said.

I was weary. After two weeks on the main line of resistance, those of us in Easy Company were a sorry sight for the eyes—and hard on the nose. Our hair was matted, faces unshaven, uniforms grimy and stinking from our sweat. We’d had little sleep, little quiet, little hot food. In a couple of days we moved north, up the Cherbourg Peninsula. It was primarily a time of rest, relaxation, and eating French beef, a delicacy that we enjoyed to the hilt. On at least one occasion we had an afternoon trip into Cherbourg, which had been liberated in bloody fighting.

In early July, we moved back to a location near Utah Beach for eventual departure back to England and whatever else this war had in store for Easy Company. This time, our resident scrounger, Alton More, was getting more tactful in his finds. He walked into camp one afternoon carrying two cardboard boxes, one of canned fruit cocktail and the other of pineapple. We feasted as he told us how he’d gotten it from the main supply depot. Others joined him on his runs in subsequent days and we ate like kings.

The day before we were to board an LST for our trip across the Channel, More outdid himself.

“Check it out, Malark,” he said, showing me a U.S. army motorcycle and sidecar he’d wrangled from the main motor pool and hidden in the sand dunes near Utah Beach. He’d asked Compton about taking it back to England. “If you can get it on that ship, I don’t care,” said Buck, who was in charge because Winters had been sent back to England with a leg wound.

The next day, July 11, More moved the cycle up to the fore dune. We had worked out a hand signal for him to ride over the dune. I had tipped off the navy personnel that we had a last-minute vehicle coming aboard, without mentioning it was an American motorcycle and sidecar. When Easy Company had boarded, Compton and I were standing on the ramp. I signaled More. He came roaring over the dune and up the ramp like some sort of barnstorming cycle king.

We were the first off the LST at Southampton. More and I rode the cycle back to Aldbourne. On the way, I asked him what we would do for gas, and he said we’d stop at army depots.

He opened his saddlebag and pulled out a stack of phony fuel tickets he’d concocted, but darned if they didn’t work. We had no problems getting gas. And so with Alton driving and me in the sidecar, we zipped through the English countryside with smiles wide and fists pumping the air like a couple of carefree American boys who’d left the war behind.

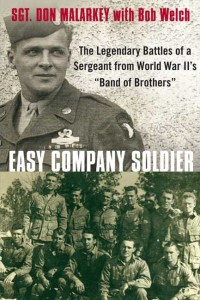

Excerpted from Easy Company Soldier: The Legendary Battles of a Sergeant from World War II’s “Band of Brothers” by Don Malarkey with Bob Welch.

Copyright © 2008 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

DON MALARKEY is the author of Easy Company Soldier: The Legendary Battles of A Sergeant from WWII’s “Band of Brothers” with Bob Welch. He was born in 1921, and grew up in Astoria, Oregon. After trying to enlist in several branches of the service, he was drafted in 1942 and spent more consecutive days in combat than any other member of “E Company,” 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne—the most recognized fighting unit in American history.