Editor: Michael Spilling and Consultant Editor: Chris McNab

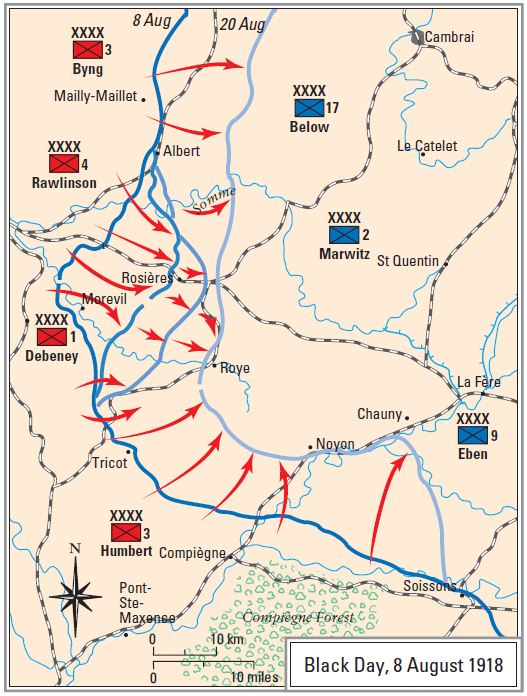

The attack on the Cambrai–St Quentin sector was intended as the British portion of a joint offensive all along the Western Front. French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the architect of Allied strategy, wanted attacks on the entire length of the front to prevent the Germans from focusing their dwindling resources in one area only.

The British attempt, in tandem with the American attack in the Meuse- Argonne sector and French attacks to the north, aimed to force the Germans out of the powerful set of fixed defenses known as the Hindenburg Line. If the Allied armies could unhinge that line, they would face no insurmountable obstacles to the Rhine River. Breaking the line before winter afforded the Germans a chance to pause and refit could produce victory before the end of the year. Although primarily a British operation, the forces dedicated to breaking the Hindenburg Line in the Cambrai–St Quentin sector included one French army, the Australian Corps, and the American II Corps.

The Battle of Cambrai–St Quentin Begins

Preliminary assaults on German positions along the Canal du Nord succeeded in forcing the Germans back almost 6.4km, a huge achievement by World War I standards. The attack also produced 10,000 German prisoners of war, an indication that the enemy’s morale might be breaking. Nevertheless, the American/Australian attack on the St Quentin Canal on 29 September at first fared poorly, in part due to American inexperience. The ‘Yanks’ tended to advance too far too fast, failing to neutralize German positions in their rear. Surviving German troops could then fire into the backs of advancing American troops. Staff coordination between British and American officers was also imperfect, leaving the Americans with inadequate artillery support.

Another reason for the setback emerged from the strength of well planned German positions. The Germans had emptied a key tunnel of the Cambrai–St Quentin Canal and turned it into a mini-fortress, complete with field kitchens, hospitals and barracks.

Once inside the tunnel, troops were well protected from Allied artillery barrages. The Germans had also carefully defended the approaches to the canal with barbed wire, interlocking machine-gun positions and pre-registered artillery pieces. The canal tunnel thus represented part of one of the most formidable defensive systems to be found anywhere in 1918. Despite their initial setback, the Americans regrouped and assaulted the canal again. Two raw and inexperienced American National Guard divisions attacked with support from British heavy artillery and tanks.

The end of WWI was close at hand

Driving forward, the Americans captured the critical part of the German trench system around the present-day American military cemetery of Bony. Then, alongside the Australians, they attacked both ends of the St Quentin tunnel simultaneously, trapping the Germans inside and winning an important victory. That success allowed the British to press on towards the strategic road juncture of Cambrai–St Quentin, which Canadian troops took on 9 October. The conditions of the pillaged town and the demoralized state of German prisoners of war convinced the Allies that the end of the war might indeed be in sight. Meanwhile, at the German resort town of Spa, the German High Command had come to the same conclusion. They therefore began preparations to sue for peace.

Dr. Chris McNab is the editor of AMERICAN BATTLES & CAMPAIGNS: A Chronicle, from 1622-Present and is an experienced specialist in wilderness and urban survival techniques. He has published over 20 books including: How to Survive Anything, Anywhere, an encyclopedia of military and civilian survival techniques for all environments. Special Forces Endurance Techniques, First Aid Survival Manual, and The Handbook of Urban Survival.