by Kevin Maurer

Writing Damn Lucky was an amazing experience, but one of the frustrations was all the great stuff I left out because it didn’t fit into the narrative. This story is about a crash, a fisherman, and a scarf.

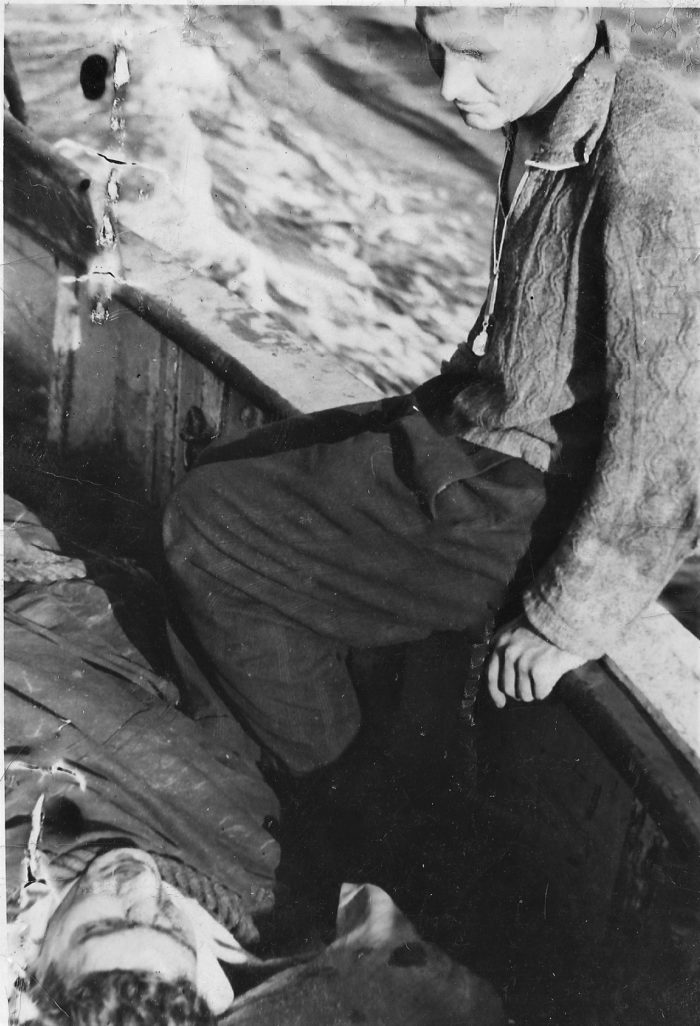

Photo courtesy of Linda Berkery.

It’s July 1943 and Bill DeSanders—who makes a cameo in Damn Lucky at a pivotal time—has an ear infection so Captain Richard Carey took his place in the pilot seat on his crew with Second Lieutenant William Styles in the co-pilot seat. This was Styles’s eighth mission. The target was aircraft factories in Warnemunde, a German town on the Baltic Sea. Cloud cover pushed the bombers to Kiel, where anti-aircraft fire—called flak—tore into the squadron.

Their bomber lost its No. 2 engine and struggled to keep up with the others. Soon, other engines failed forcing Styles and Carey to ditch into the sea fifty miles from Denmark.

Carey and Styles escaped the quickly sinking plane. The rest of the crew was in the radio room at the center of the aircraft. Two severely injured gunners—Robert Lepper and Maynard Parsons—were pushed through the overhead hatch by the other six crew members who were trapped and went down with the plane.

“Griffith was struggling to get out of the hatch as the plane was sinking, that is the last I saw of him,” Styles wrote in a report later.

Nearby, a Danish fishing boat saw the B-17 hit the water and cruised over to pick up any survivors. Bobbing in the water with their Mae West life jackets inflated were the two pilots—Styles and Carey—and the two gunners—Lepper and Parsons. The boat’s crew—Captain Svend Pedersen and Viggo Skouenborg —hauled the men onto the deck like a fresh catch. Lepper’s wrist and legs were fractured, and the fishermen broke up crates so they could splint the limbs. When they finished, Lepper was wrapped in a blanket to stay warm.

While they waited for rescue, Skouenborg shot pictures of the Americans. A few show Styles posing with Carey. Both men look traumatized. They’d just endured bone-jarring flak and crashing into the North Sea. More than half their crew was dead and there was a good chance they were prisoners of war. Styles gave Skouenborg his silk survival scarf in gratitude. The scarf had a map of France and Germany printed on it. Made of silk so that it didn’t make any noise at night or when an airman was hiding, the maps were an essential part of the crew’s evasion kit. The fisherman waited in the area for six hours hoping an American rescue plane would come for the crew, but the crash was too far from England. Out of options because a German fighter reported the downed bomber, they were forced to return to port in Esbjerg, Denmark, and turn over the crew.

An ambulance and a small crowd met the boat at the dock. The Germans arrived soon after, according to an account in a resistance newspaper called Vestjyden, and kept Lepper on the deck of the boat instead of the ambulance. The crowd protested, but a sharp whistle from the German officer brought more troops who threatened the crowd and drove them away from the dock. For two hours, Lepper waited in agony for a German ambulance.

“While the poor man was lying there racked with pain a German officer strutted about smiling cynically every time the injured airman moaned with pain,” a witness wrote in the newspaper. “The brutality shown here by the Germans to a severely injured and helpless adversary once more stresses their cowardice and sadistic leanings. It is a comfort that the day of reckoning will soon be here, and then the German beasts will have the bill presented with interest and compound interest. We are in complete agreement on that.”

The airmen were taken to Dulag Luft and then Stalag Luft III, the POW camp for aviation officers in Sagan, Germany until the end of the war.

Fast forward to 2017.

A reporter at the local paper in Esbjerg got an email from Linda Berkery, Style’s daughter, asking for more information about what happened that day. The reporter dug in and when the story was published, the fishermen’s families recognized the photos and contacted Linda. Soon, decedents from the airman and Danish fishermen connected via social media and phone.

But the biggest surprise came when Jesper, the son of the fisherman turned photographer who shot the photos of Styles and crew, contacted Linda.

“As a kid, I listened to my father with tall eyes and ears when he told me this dramatic rescue story,” he told Linda.

Then the kicker.

“Your father gave my father two silk maps as a thank you for the rescue,” he said. “Those maps are still in my possession. I would love to give you one—my pleasure.”

Linda accepted the gift and waited for weeks for the scarf to arrive. When it did, she took it out and held it to her face.

“Maybe it was just the sun on the front porch, but I felt my father’s warmth as the scarf rested in my shaky hands,” she wrote in an essay about the scarf. “I breathed deeply and lifted the silent silk map to my face, careful to avoid the tears, but it wasn’t silent at all. I heard the North Sea and voices from a summer evening in 1943. I had re-connected with my father.”

Want to find more information on this mission and every 100th Bomb Group mission? Head over to the 100th Bomb Group Foundation.

Kevin Maurer is an award-winning journalist and three-time New York Times bestselling co-author of No Easy Day, No Hero and American Radical among others. For the last eleven years, Maurer has also worked as a freelance writer covering war, politics and general interest stories. His writing has been published in GQ, Men’s Journal, The Daily Beast, The Washington Post, and numerous other publications.