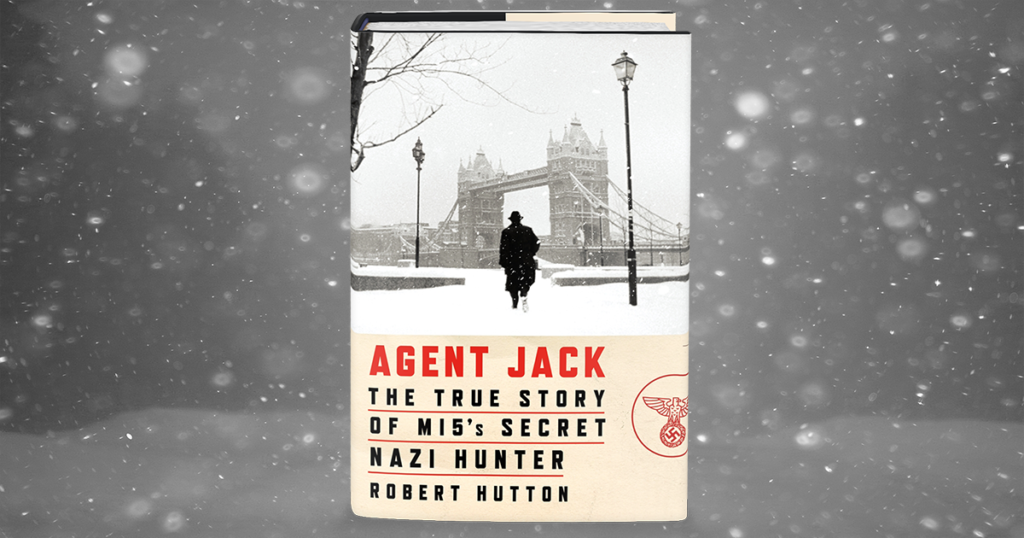

by Robert Hutton

Get a sneak peek at Agent Jack, in which Robert Hutton brings to light the never-before-told story of Eric Roberts, who infiltrated a network of Nazi sympathizers in Great Britain in order to protect the country from the grips of fascism.

Mr. Jones, assistant controller at the Westminster Bank, put down the phone in a puzzled mood. There was much to trouble any Englishman that day, even one sitting, as Jones did, in the headquarters of one of the City of London’s most important banks. The previous day, 10 June 1940, Italy had entered the war on Germany’s side. And while Adolf Hitler was gaining allies, Britain was running out of them: across the Channel, the French were on the point of surrender in the face of an unstoppable German advance. Britain was Europe’s final bastion of freedom and Hitler’s next target. The country was drawing up plans to face the most serious invasion threat to its shores in almost a thousand years.

But at the front of Jones’s mind was the conversation he’d just finished, with a mysterious man from the military who wanted the Westminster Bank’s help.

What was most puzzling was the nature of the request. It had come the previous day in a letter – marked ‘Secret, Personal’ – from the man he’d just spoken to, Lt Col Allen Harker. Harker’s question was in itself simple enough: could the bank release one of its staff immediately for special war work? Harker had been vague in his letter about both the work and what he called simply ‘my organisation’, but when Jones consulted his superiors, the answer was clear: there was no question of refusing. In the country’s hour of need, the Westminster Bank would not be found wanting.

In Jones’s view, the man the government wanted was no great loss to the Westminster Bank. Eric Roberts had been a clerk there for fifteen years, during which time he had failed to distinguish himself. Indeed, he was best known for playing tiresome pranks on his superiors and even on customers. It was typical of Roberts that at the very moment the future of the nation hung in the balance, and when apparently he alone of the Westminster Bank’s staff could make a difference, he had gone on holiday.

It wasn’t just Roberts’s career that was unremarkable. He had married a fellow bank clerk and they now lived with their two young sons in an unexceptional semi-detached house in the unexceptional London suburb of Epsom. Roberts was ordinary in every way.

But Harker had been clear that it was Roberts they wanted. Jones began to dictate a letter, confirming what he’d said in the phone call, that Roberts would be made available immediately. Even Harker’s address was mysterious: Box 500, Parliament Street.

To a better-informed man, this would have been the clue. Box 500 was the postal address of the secret state. The day before Jones spoke to him, Harker – Jasper to his friends – had himself received a summons. He had been called to see the prime minister, Winston Churchill, who had appointed him director of the Security Service, MI5.

Jones knew none of this. And although he did know that in wartime one was not supposed to ask questions, he could not help adding a line to his letter: ‘What we would like to know here is, what are the particular and special qualifications of Mr Roberts – which we have not been able to perceive – for some particular work of national importance?’

***

Two months after that phone call, as the sun faded at the end of a fine summer’s day, a pair of young men in Leeds set out to burn down a shop.

That night, as every night since the start of the war, the blackout was strictly in force. In an effort to stop lights from the ground helping enemy bombers to find their targets, the country plunged itself into darkness. On top of rationing and the other hardships of wartime, people had the nightly chore of covering every window and doorway with thick black cloth to prevent any possible leak of light. Air-raid wardens patrolled towns whose street lamps were unlit, looking for signs of light and warning transgressors. As pedestrians groped their way through the darkness, forbidden even from lighting a cigarette, cars navigated by the faint glow of masked headlights. Accident rates – and crime rates – soared.

There was no moon as Reginald Windsor and Michael Gannon walked through the pitch-dark streets. Neither man looked like an aspiring arsonist. Windsor, at twenty-seven, was the older of the pair by a year. An unexceptional looking young man with a tendency to talk too much, he worked long hours in the newsagent and tobacconist he owned, while Gannon worked as a driver. They could have passed for any two young men on a night out. But theirs wasn’t a friendship forged over sport or a drink in the pub. Their bond was fascism.

Local politicians, as well as those in London, were the target of Windsor’s anger. He was pretty sure that Leeds’ city councillors were lining their own pockets at the expense of honest taxpayers like himself. And it was these thoughts that had led Windsor, like 40,000 others, to join the fascists of Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union. Mosley argued that the political system was failing the people and destroying Britain and her empire. The age of democracy was over. What was needed was a strong leader with the power to bring about change, unfettered by Parliament. These ideas had enjoyed some wider popularity in the early 1930s, but as people had seen how they worked in practice in Germany, support had ebbed – one reason that in 1937 Mosley had dropped the final two words from the name of the British Union of Fascists. Mosley became increasingly associated with the violence of his Blackshirts, the uniformed young men who were supposed to keep order at his events. He also began to talk more and more about ‘the Jewish Question’.

In the BU, Windsor had found his cause. He’d also found some friends. He became the treasurer of the BU’s North Leeds branch. As war loomed in 1939, he, along with other members of the party, campaigned for peace. As Mosley argued, war with Germany would be a ‘world disaster’. And the people pushing for it were the usual suspects: the Jews, angry that Hitler had ‘broken the control of international finance’.

Once war broke out, a lot of BU members disappeared. Some had been called up to the military, and some simply stopped coming to meetings. But Windsor kept the faith. In March 1940, he signed up to help campaign for the BU candidate in the local parliamentary by-election. In a sign of the shift in public mood, the party won just 722 votes. The only other candidate, a Conservative, swept to victory with 97 percent of the vote.

At the start of May, Chamberlain was forced to resign as prime minister after the Allies were routed by the advancing German forces in Norway, and was replaced by Winston Churchill. At the end of the month, France collapsed in the face of a swift German advance. This military disaster seemed, to Mosley’s supporters, to vindicate his stance. Why were British soldiers being sent to die to defend France when French soldiers had so little interest in fighting themselves? Hitler had shown himself to be the greatest military commander of the age, but he wanted to come to terms with Britain, so why not do just that?

This view wasn’t confined to fascists. The Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, put out diplomatic feelers to Benito Mussolini’s government in Italy to see if it could help broker peace talks with Germany. Churchill, weeks into his job as prime minister, had to outmanoeuvre his own colleague to win support for continuing the war.

Churchill’s pledge to fight on was made more credible by what was to happen that week on the other side of the Channel. With hundreds of thousands of British troops stranded at Dunkirk, the Royal Navy ordered every ship on the south coast of England to sail for France. Over the space of nine days, between 26 May and 4 June, more than 330,000 men were rescued, despite attacks from the German navy and air force. Britain now had the troops to fight Hitler, even if they’d been forced to leave much of their equipment behind.

But this victory in turn raised an immediate question on both sides of the Channel: if Britain could move hundreds of thousands of men from France to England under enemy fire, why couldn’t Germany? German planners began to work out how they might pull off such a feat, while in Britain the generals debated how best to fight off the invader. Everywhere there were reminders that the government expected the Germans to arrive soon: obstacles in fields to stop planes from landing; road signs removed for fear they might assist the enemy.

If ordinary Britons questioned whether invasion really was a possibility, the government did its best to remove such doubts when, in the middle of June, it sent a leaflet to every household in the country entitled ‘If the Invader Comes’. Its message was that everyone must play their part in the coming struggle. ‘Hitler’s invasions of Poland, Holland and Belgium were greatly helped by the fact that the civilian population was taken by surprise,’ the leaflet explained. ‘They did not know what to do when the moment came. You must not be taken by surprise.’ The public response was mixed. Some people were terrified, while others felt the leaflet’s patronising tone was ridiculous.

One of Churchill’s first acts as prime minister was to respond to growing fears about the loyalty of the British Union by outlawing the party and locking up Mosley and the group’s other leaders. The popular press welcomed the move. ‘Britain’s pocket Fuehrer is hauled in,’ the Daily Express trumpeted. The Daily Mirror felt this was long overdue. ‘Precautions that should have been taken years ago are now being applied to the Judas Association (British Branch),’ it told its readers.

Windsor had responded to the crackdown by destroying all of his BU branch’s paperwork – he said he didn’t want the police to find anything that might lead them to other members. But in secret, he fought on. He kept his branch going, organising meetings in the back room of his shop where his little group discussed how Britain had been dragged into war against its natural ally by the Jews, and what they might do to restore common sense to the nation. Which would clearly come only with a swift military defeat for the Churchill government.

How could they help to bring that about? They discussed carrying out sabotage operations against airfields and factories. They considered whether they could gather military intelligence and pass it to Germany. And they talked about whether they could blow things up during the blackout. It was the final idea that Windsor and Gannon planned to put into action that August evening. By starting a fire in Leeds city centre, they hoped to guide the Luftwaffe’s bombers in. They would strike a blow against the war effort, against the blackout, and for Germany. And they would do it in a way that chimed with one of Windsor’s personal grievances.

Sidney Dawson and his wife Dolly together ran a small chain of shops across Leeds. Known locally as ‘the Murder Man’, thanks to his slogan ‘We Don’t Cut Prices – We Murder Them’, Sidney was the kind of competitor – undercutting his own business – that Windsor loathed. This was also, he knew, exactly the sort of business Mosley had in mind when he attacked ‘alien finance’ and ‘price-cutting’: the Dawsons were Jewish. ‘A cheap place where actually it was all rubbish,’ was Windsor’s verdict on Dawson’s. Even though the stock was cut-price, ‘it was not worth the price the fellow used to ask’.

So, Windsor had selected as the evening’s target a branch of Dawson’s on Wellington Road, which ran southwest out of the city centre. The shop had the strategic advantage of being close to several railway yards and right next to the main London, Midland and Scottish Railway line. Some nearby gas towers would also burn well if bombed.

The buildings along Wellington Road were black with soot and grime. Tramlines ran down the middle of the wide, cobbled street, but there was no sign of activity that night. The two men approached Dawson’s cautiously and stood in the doorway. The building was silent. They took turns to peer through the letter box. No one there. But then, just as they were preparing to act, they heard a noise from the flat above the shop. The pair panicked and fled.

Once they’d got to what they judged a safe distance, they collected themselves and considered what to do. They wanted to go through with their plan, but they didn’t dare go back to Wellington Road. There was, however, another branch of Dawson’s about twenty minutes’ walk away. It wasn’t quite as central as the Wellington Road branch, but it was right next to a railway viaduct, and another gasworks. Surely those would be useful targets for the Luftwaffe?

This time, the two were determined to go through with their mission. As they peered through the second shop’s letter flap, they could see some kind of curtain on the other side, probably a blackout measure. They didn’t have much to start a fire with, except a cigarette lighter, so they pulled out the petrol soaked wool from it, and started to push it through the slit.

Just then, the slow rising and falling wail of the air-raid sirens began. The bombers were coming! Windsor would later claim he’d told Gannon to wait for the raid to pass, but it seems unlikely that the two nervous young men would have been prepared to stay crouched in a shop doorway as the sirens howled above them, especially when their purpose was to help the bombers.

With Windsor standing with his back to the door to conceal his friend, Gannon lit the wool from the lighter and quickly pushed it through the door. They saw a flash as some paper on the floor caught fire, and ran.

The two were therefore not around to see their arson attempt thwarted. After they’d disappeared, someone spotted the flames in the shop and called the fire brigade, who put it out before much damage had been done. In any case, there was no Luftwaffe raid. The enemy planes that had been spotted over England’s northeast coast sixty miles away turned back without attacking.

Windsor and Gannon may have been disappointed not to have caused a larger fire, or to have summoned the bombers, but they still succeeded in scaring Sidney and Dolly Dawson. Two weeks after the arson attempt, the couple put their only child, twelve-year-old Olive, on board the Duchess of Atholl liner to Canada, where she would spend the next four years living with her aunt. In their view, England wasn’t safe for Jewish children anymore.

What neither Windsor nor Gannon suspected that Sunday evening, as they hurried away through the darkness with the sirens sounding the single high note of the All Clear, was that MI5 was already on their trail.

***

Three weeks earlier the Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, responsible for espionage operations outside British territory, had passed a letter to its sister agency MI5, the Security Service. From someone calling himself A. D. Lewis, it warned that some members of the banned British Union of Fascists were continuing to meet in Leeds. A second letter repeating the allegation arrived at MI6 a fortnight later, which, since domestic counter-subversion was MI5’s job, they again passed on.

That summer, MI5 was a service in chaos. The declaration of war had led to a huge expansion of its responsibilities, and a recruitment drive to match. In search of more space, the organisation shifted its offices from the seventh floor of Thames House, a few minutes upriver from the Houses of Parliament, to Wormwood Scrubs prison. Sitting in the recently vacated cells – and, on occasion, accidentally getting locked into them – the staff were overwhelmed by reports of German spying and sabotage sent in by suddenly suspicious members of the public.

But the letters from Lewis were noticed, and taken seriously. Three weeks after the first one arrived at MI5, and a couple of days after Windsor and Gannon’s arson expedition, Lewis visited London, where he was interviewed by MI5 officers responsible for investigating right-wing groups. He had a story to tell.

Two months earlier, shortly after the BU leaders had been arrested, Lewis had walked into Windsor’s shop and, after checking they were alone, turned back the lapel on his coat to reveal a badge with the distinctive lightning-bolt-in-a-circle of the BU. ‘I am not a copper,’ he’d begun. Instead, he said, he was a bus driver called Wells, and a fellow fascist. He also claimed that he’d been sent to make contact with Windsor by a mutual acquaintance in the West Leeds BU. According to the account he gave MI5, Lewis was a loyal citizen who had learned that Windsor’s group was still meeting in secret, and had decided to find out what it was up to.

As well as Windsor and Gannon, there were around half a dozen fellow BU members present. Lewis told MI5 that the group had come up with three plans to further the fascist cause: throw bombs; sabotage factories and airfields; and pass information on to Germany.

Lewis’s account excited the Security Service. ‘Although these people are of no great importance in themselves the case is worthy of mention in that it throws considerable light on the general question of Fascist and “Fifth Column” activities in this country,’ a report noted. This was the question greatly troubling MI5 at the time: how many disloyal people were there in the country, and how might they be uncovered?

Around the world it was accepted that part of the reason for Hitler’s swift advance through Europe had been networks of agents behind the lines, so-called ‘Fifth Columnists’ who passed information to the advancing troops, sheltered parachutists and carried out sabotage operations. The Chicago Daily News told its readers that the capture of Norway’s cities was not the work of soldiers. ‘They were seized with unparalleled speed by means of a gigantic conspiracy,’ it explained. ‘By bribery and extraordinary infiltration on the part of Nazi agents, and by treason on the part of a few highly placed Norwegian civilians, and defence officials, the German dictatorship built its Trojan Horse inside Norway.’ The article, which was reprinted in several British papers, claimed that the commander of a Norwegian naval base had been ordered not to oppose the German forces, and that a minefield elsewhere had been disconnected from its control point. If anyone was inclined to doubt these tales, it was undeniable that in the hours after Germany invaded Norway, the country’s former defence minister and leader of its fascist party, Vidkun Quisling, had attempted to seize power and order troops to stand down. In Britain, his name rapidly passed into the language as a synonym for ‘traitor’.

MI5’s job was to find the Fifth Columnists in Britain before the Germans invaded. One avenue was to monitor German citizens still living in Britain, but British fascists were the next obvious people to investigate.

MI5 sent Lewis back to Leeds and considered their options. The idea of allowing Lewis to work the case on his own was rejected. Although he was obviously a man of some initiative, and MI5 were inclined to think him both honest and loyal to his country, a case such as this required considerable subtlety. It was vital not to cross the line from undercover operative to agent provocateur – from observing illegal acts to instigating them. As they questioned Lewis, it had become clear to the MI5 officers that he had not observed this rule. Leaving the ethics of such behaviour aside, it would scupper any prosecution if the government’s witness was revealed to have encouraged the wrongdoing.

So they decided to send in their own man alongside Lewis. On Friday 23 August, Eric Roberts, late of the Euston Road branch of the Westminster Bank, arrived in Leeds.

Robert Hutton has been Bloomberg’s UK Political Correspondent since 2004. Before that he was a reporter on the Daily Mirror, and before that he built robots and taught computers to play Bridge at Edinburgh University. He’s married with two sons, and lives in South East London.