by Suzanne Mettler and Robert C. Lieberman

In the following excerpt from their book Four Threats, Suzanne Mettler and Robert C. Lieberman discuss the violent rise of Southern Democrats in post-Civil War Wilmington, North Carolina that turned back decades of progress in the city.

In the 1890s, Wilmington was North Carolina’s largest urban center and a beacon of progress both for the post–Civil War South and for the nation generally. It boasted the hallmarks of a modern city: electric lights, streetcars, and, most strikingly, a politically empowered and growing black middle class. African Americans made up the majority of the population, and they worked as skilled craftsmen in a wide array of trades and owned numerous businesses, including most of the city’s restaurants—which were frequented by whites as well as blacks. Three members of the Board of Aldermen were African Americans, as were numerous public-sector employees. The city possessed a black-owned newspaper, the Daily Record, one of only a handful in the nation. President William McKinley appointed an African American named John Campbell Dancy to be the collector of customs for the city’s port, making him more highly paid than the state’s Democratic governor and other high-ranking state officials, all of whom were white, not to mention most white citizens in Wilmington. Several civic organizations established by the black community flourished. Black literacy rates were growing, as was homeownership; by 1897, more than one thousand African Americans owned some property. Democracy, as indicated by political inclusion as well as the expansion of social and economic rights, appeared to be on the rise.

However, white elites in North Carolina saw in these developments not progress but the demise of the world as they had known it—their “heritage,” as they viewed it—and they had grown even more troubled by political developments statewide in recent years. Their party, the Democrats, lost power when the Republican Party, of which African Americans were the core constituency throughout the South, joined forces with the insurgent Populist Party, which included many low-and middle-income whites. In 1894, this multiracial “Fusion” coalition managed to sweep the majority of seats in both chambers of the state legislature, several congressional seats, and even a seat in the US Senate; in 1896, it won even larger victories, including the governorship. It was at that juncture that Democratic Party leaders across the state, together with prominent businessmen, made a decision: it was time to push back, shut out the opposition, and reclaim political power once and for all. Over a period of six months, they hatched plans and chose to make Wilmington the focus of their campaign and the “center of the white supremacy movement.” On a single day in November 1898, they would turn back decades of progress in the city.

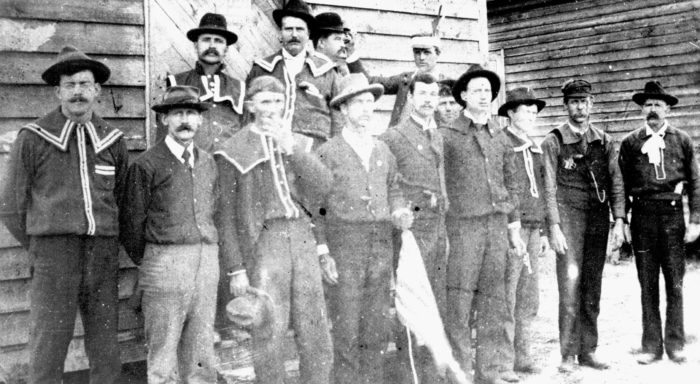

To lay the groundwork, first Democrats needed to recapture control of the state legislature in the fall elections. In the weeks before Election Day, two white supremacist groups, the White Government Union (WGU) and the Red Shirts, a terrorist arm of the Democratic Party, held rallies and roamed black neighborhoods, armed and on horseback, to intimidate African Americans and prevent them from voting. Newspapers brimmed with white supremacist rhetoric. Gun sales spiked. Republicans feared violence, and Democratic leaders pressured them to withdraw candidates from the ballot if they wanted to be safe. The tactics worked, and Democrats won back the legislature. Now the stage was set for them to retake control of Wilmington.

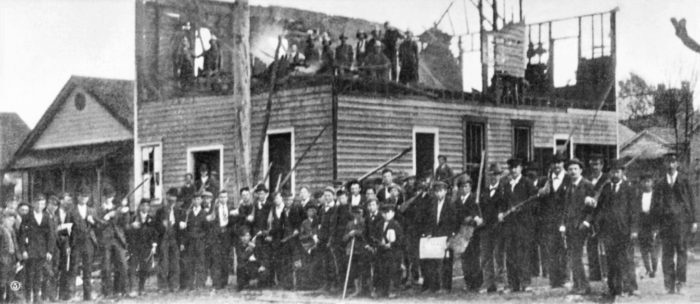

Two days after the election, early in the morning on November 10, nearly two thousand white men from the WGU and several paramilitary groups, including the Red Shirts, gathered at the city armory, brandishing rifles and pistols. The mob marched into the city, proceeding directly to the offices of the Daily Record, where they stormed their way inside, destroyed furniture and the press, then spread kerosene, set fire to the building, and watched as flames devoured it, as shown in the photo.

The paramilitary groups then advanced through black neighborhoods, killing hundreds of individuals as the day wore on. They also dragged several prominent citizens from their homes and banished them from the city. Those expelled were predominantly African Americans, including successful businessmen, the sheriff and chief of police, and open opponents of white supremacy. Some they first threw into jail overnight, while others they took directly to the train station, led by soldiers with fixed bayonets, and forced them to leave town. In addition, they exiled several white Republicans and Populists, mobs jeering at them with cries of “white nigger” and threatening to lynch them.

Later that afternoon, while violence reigned in the city, the white leaders forced resignations—at gunpoint—by members of the biracial Fusionist government. At a mass meeting the evening before, hundreds of white residents, primarily businessmen, merchants, lawyers, doctors, and clergy, had endorsed—with a standing ovation—a “White Declaration of Independence,” which included resolutions that the elected leaders must resign. Forced to do so, the mayor and members of the Board of Aldermen relinquished their positions, and a new government of white Democrats—handpicked by those who organized the insurrection—took power. When the chaos subsided, Josephus Daniels, a leader of the insurrection and the publisher of the News and Observer, wrote that the events ushered in “permanent good government by the party of the White Man.”

It was a coup d’état, American style. No one came to the aid of those who had been pushed out of power in Wilmington. African American leaders pleaded for help from President McKinley. So did the state’s two US senators, Populist Marion Butler and Republican Jeter Pritchard. But the president claimed that he could not act without a request from Governor Daniel Russell. A Republican elected in 1896, Russell faced threats of impeachment from the Democrats and of bodily harm from the Red Shirts, so he made no request for federal intervention. McKinley consequently did nothing, and thereafter took a trip to Atlanta in a show of “sectional reconciliation.”

The Democrats quickly took steps at the state level to make their power permanent. Within a few months, they had secured a new constitutional amendment that imposed poll taxes, literacy tests, and other measures that would disenfranchise all African Americans and a good many poor whites for seventy years to come. Democrats in other states throughout the South who also had found themselves challenged by Republicans and Populists now began to replicate these efforts, if they had not undertaken them already. The establishment of racial segregation in all aspects of social life—American apartheid—followed. The multiracial democracy that had been on the rise was vanquished, replaced by white supremacist, authoritarian rule.

© Copyright Robert C. Lieberman and Suzanne Mettler 2020

Robert C. Lieberman is Krieger-Eisenhower Professor of Political Science at Johns Hopkins. He has received fellowships from the Russell Sage Foundation and the American Philosophical Society.

Suzanne Mettler is the John L. Senior Professor of American Institutions in the Government Department at Cornell University. She is a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Radcliffe Institute Fellowship, and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017.