by Tom Clavin

There are two reasons to write about James Butler Hickok right now. One is baseball. We are in what the sport’s scribes call the “dog days” of the season when the pennant races become as hot as the temperature and last-minute trades are made to boost the chances of the top teams. The second is the 146th anniversary of Wild Bill’s death in Deadwood, on August 2, 1876.

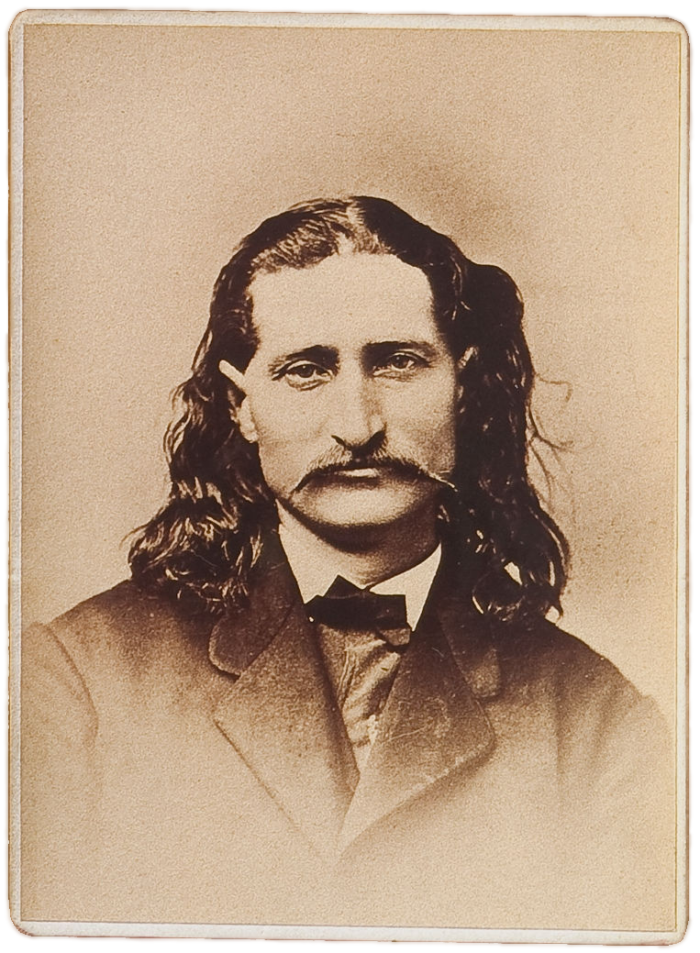

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Hickok and baseball? Yes, indeed. In 1866, he was leading a pretty good life for a 29-year-old man. He was paid well, from $75 to $100 a month, to guide U.S. Army missions and had become a celebrity thanks to profiles that had appeared in eastern publications. In between the journeys, Wild Bill could spend time at the gaming tables in Kansas City, dressed in much finer clothes than on the trail. He enjoyed the ambiance of saloons, the risks and rewards of gambling, the attention of the women (it did not matter that many were prostitutes), the alcohol, and dressing well. With a good-natured grin, Hickok tolerated the ribbing he received for being possibly the only man in Kansas City who bathed every day. When it was time for the next mission to kick off, it was back into buckskins and moccasins and being alert for hostiles.

One of his less-known exploits at the time was on a baseball diamond. Hickok was a fan of the young sport and he frequented the ballfield at the corner of Fourteenth and Oak Streets. This was the home of the Kansas City Antelopes, the first baseball team in the city. It had been organized by the attorney D.S. Twitchell that July, three years before the Cincinnati Red Legs, recognized as the first professional team in the U.S. The Antelopes’ park had no grandstand or scoreboard and patrons had to sit on benches in the hot sun. Still, every Saturday afternoon patrons filed in to watch the action. One of them, when he was in town, was Hickok. He also played pick-up games with local youngsters. Then, one Saturday, he was asked to umpire an Antelopes game.

The reason Wild Bill, of all people, was asked was because the weekly contests had a habit of descending into brawls, especially if the umpire ruled on a play against the Antelopes. There was no gunplay—guns weren’t allowed within the Kansas City limits—but fists, boots, bottles, and even the occasional knife were employed against fans of the visiting team and the cowering umpire. On this particular Saturday, the Antelopes were hosting the Atchison Pomeroys. The visitors had beaten the Antelopes on their home turf and an attempt at a rematch in Kansas City had resulted in a riot and the game was canceled. “The Town Is Disgraced!” blared a headline in The Kansas City Star.

A rematch of the rematch was arranged. Hickok agreed to be the umpire. When the first pitch was thrown, he was behind the plate with what then passed for umpire’s gear. He also wore, thanks to a dispensation from the city fathers, his Colt six-shooters. His calls went undisputed.

The game was played to its completion, and the pleased crowd cheered the 48-28 victory by the Antelopes. They cheered the umpire too, who bowed to acknowledge the approval, then made his way to Market Square to take up that night’s gambling entertainment.

A decade later, a rapidly aging and eyesight-challenged Wild Bill Hickok was languishing in Deadwood, South Dakota. He was there to win enough money gambling that he could return to his new wife, Agnes, a circus impresario, and they could set themselves up in Cincinnati. But the cards had not been kind to him.

On Wednesday, August 2, 1876, Hickok entered Nuttall and Mann’s No. 10 saloon at 3 p.m. dressed in his longtime favorite outfit, which included a Prince Albert frock coat, calfskin boots, and black sombrero. As usual, he had bathed, then had a noon-ish breakfast with his good friend Colorado Charley. When he entered the saloon he was easily the best-dressed and most presentable man in the place. He wore his gunbelt the usual way, with the pistols up near his hips, handles out.

Hickok chatted with another friend, Harry Young, at the bar and downed a shot of whiskey. He saw a poker game already in progress that included Carl Mann, Charles Rich, and Capt. William Massie. The latter was a 45-year-old former captain of steamboats that plied the Missouri River who had contracted gold fever, then discovered he preferred poker to prospecting. Rich was in the seat against the wall. Usually, Hickok did not even have to ask, the man in the wall chair would immediately give it up, but in this instance, Rich did not. Reluctantly, Hickok sat in a chair on one side of the poker table. At least it gave him an unobstructed view of the saloon’s front door, and he was aware that a few steps behind him there was a rear exit.

The game continued for close to an hour. None of the men apparently had any other pressing business and playing poker in the cool and dark confines of the saloon was as good a way as any to pass the sultry summer afternoon. The only sour note was that several times Hickok asked Charles Rich to exchange seats with him and the latter refused—the young man was either being unnecessarily obstinate or was having a run of good luck and did not want to change a thing. Mann and Massie, who were opposite Hickok at the table, noticed the plainsman’s unease, but they did not have the coveted chair against the wall to offer. It didn’t help Hickok’s mood that the cards were, again, going against him.

Lady Luck continued to defy him. Hickok called out to Young for a loan of $50, as he was almost cleaned out. The bartender brought that amount in chips over to the table. Referring to Massie, Hickok remarked, “The old duffer broke me on the last hand.” Those would turn out to be Wild Bill Hickok’s last words.

Jack McCall entered the No. 10 saloon. For his purpose, it paid to be a somewhat small and nondescript man. He stood at the bar, and over time worked his way along it, toward the poker table with Hickok and his companions. If Hickok had noticed him entering the front door, he dismissed McCall . . . or, that is one explanation. Surely, he would have recognized McCall from the previous night’s card game and regarded him for a few moments, still viewing him as stupid and harmless. However, it is possible that Hickok did not see him well enough to recognize him.

In any case, McCall loitered at the bar. There were no sudden movements, as the man did nothing to attract attention. For once, it seems, the sixth sense Hickok had always had about danger was not working that afternoon.

Quietly and unobtrusively, McCall eased himself behind Hickok. Rich dealt cards to the three other men. Hickok held in his hands a pair of aces, a pair of eights, and a queen. At about 4:10, McCall stepped forward and placed the muzzle of a .45-caliber revolver to the back of Hickok’s head and pulled the trigger. There was the sudden loud sound of a shot and McCall cried out, “Damn you, take that!” Hickok jerked forward. He was motionless for a few moments, then he fell sideways out of the chair.

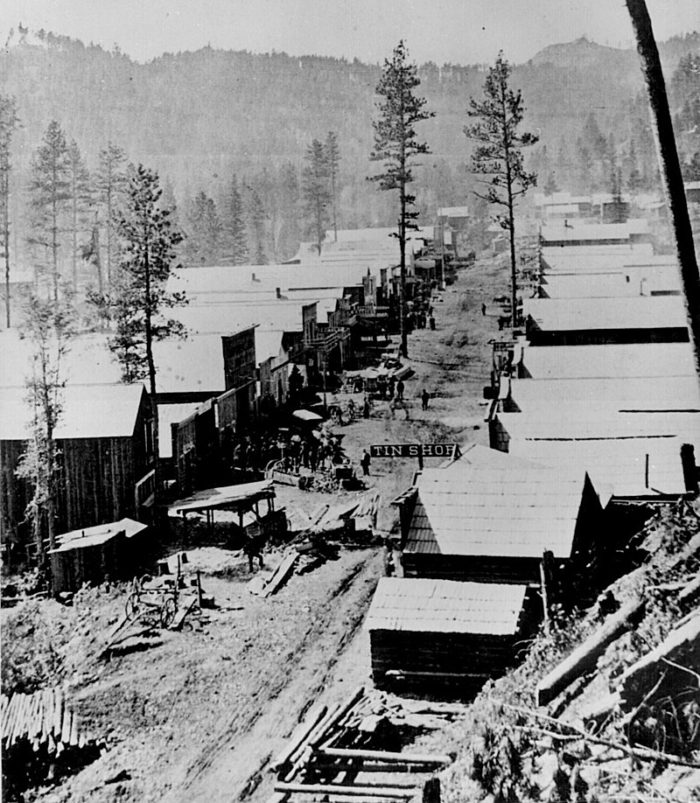

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Massie was startled by the sudden commotion and confused by a numbness he felt in his left arm. Such was Hickok’s reputation that at first Massie thought that the gunfighter, angry at losing money, had shot him. But as soon as Hickok fell to the floor, Massie saw McCall and his smoking gun standing there. He would soon learn that the bullet fired into Hickok’s skull had exited below his right cheekbone and then became lodged in Massie’s wrist. (He never had one of the most infamous bullets of the American West removed. It was buried with Massie after he died in St. Louis in 1910.)

McCall waved his pistol at others in the saloon and shouted, “Come on, you sons of bitches!” There was an abrupt rush for the front door. McCall, after attempting to fire the gun at Harry Young, tossed it aside and ran out the exit door. A saddled horse was there, but McCall fell off it because the saddle had not been tightened. He resumed running. He paused to try and hide out in, appropriately, a butcher shop. McCall could hear out on the street one, two, then many voices yelling, “Wild Bill has been shot!” and “Wild Bill is dead!”

There was, alas, no doubt about that. Hearing the shouts, Colorado Charley rushed to the No. 10 saloon where he met Ellis Peirce, a Deadwood barber and coroner, who determined that Hickok had “bled out quickly.” He had died immediately . . . and he never saw it coming. In one hand were the cards he had been dealt, to be forever known as a Dead Man’s Hand. It was also found that of the six bullets in McCall’s pistol, five were defective, meaning the only “good” bullet in the gun was the one shot into Hickok’s head.

Obviously, McCall had not planned an escape because he left his hiding spot and just ran down the main street, kicking up dust as he went. Harry Young, after recovering from the initial shock of seeing Hickok shot, was giving chase, and by ones and twos others on the street joined in. Most people, however, fled. It was being shouted along the street that it was Wild Bill Hickok who was doing the shooting, taking revenge on Deadwood for his bad luck at cards.

McCall was apprehended before he got too much farther. The August 5 edition of The Deadwood Pioneer would report simply, “The murderer Jack McCall was captured after a chase by many citizens and a guard placed over him.”

Never one to miss an opportunity, and especially now that her “lover” was dead, Calamity Jane offered that when she heard about the killing, “I at once started to look for the assassin and found him at Shurdy’s butcher shop and grabbed a meat cleaver and made him throw up his hands.”

The actual whereabouts of Calamity Jane that afternoon are unknown, but she definitely was not in the No. 10 saloon, before or after Hickok’s murder. Thus also untrue is her later account of sorrowfully cradling his body. However, to Hickok’s eternal consternation, when Calamity Jane died in 1903, she was buried next to him in the Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood.

Originally published on Tom Clavin’s The Overlook.

Tom Clavin is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include the bestselling Frontier Lawmen trilogy—Wild Bill, Dodge City, and Tombstone—and Blood and Treasure with Bob Drury. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.