by Elizabeth Winder

1955. It’s springtime in New York and unseasonably balmy. Cherry blossoms dot Central Park with pale pink, and “Melody of Love” drifts from the radio. The Pajama Game is on Broadway, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis are on Fridays at the Copa, and Truman Capote is dancing with Marilyn Monroe. Twirling to the El Morocco’s in house Cuban band, they samba and smile and swill strong martinis. Truman sweating in his pinstriped suit and glasses, Marilyn barefoot in her simple black slip, they are two cherubic little towheads, glittering with unfettered joy.

Twenty-eight year old Marilyn had just moved to New York after breaking her contract with Twentieth Century Fox. Isolated in LA but adored in New York, she was already glowing from her rich new life, full of Broadway premieres and trips to the Met, dinners with the Strasberg’s and dates with Marlon Brando. The literati adored her, especially Carson McCullers, through whom she met Truman Capote.

Truman and Marilyn were a natural match—two misfit runaways from ramshackle towns with absentee mothers and a longing to be loved. At four he’d been shipped off to Alabama aunts, she’d been shuffled between foster homes and an orphanage. Both lifelong vagabonds, they found acceptance and warmth in New York. Marilyn set up shop in the Waldorf Astoria, Truman rented a basement on Brooklyn Heights’ Willow Street—two blocks down from Marilyn’s secret love Arthur Miller.

Writers have always loved Marilyn Monroe. Karen Blixen compared her to a lion cub, Edith Sitwell saw her as a fresh-cut daffodil, “a little spring-ghost, an innocent fertility daemon, the vegetation spirit that was Ophelia.” Truman Capote was no exception, bewitched by her “vanilla pallor” skin and mussed-up hair, her uniform black dresses and constant dark glasses. Both loved animals—in between real pets they made do with toys. Truman had a wooden lion and little iron dog, Marilyn a woolen poodle with a braided leather leash. Both stared in the mirror a lot– Marilyn dropped her upper lip to hide her gum line, Truman sucked in his cheeks to look more like Rimbaud. They both loved clear manicures but bit their nails ragged. They even shared the same favorite drink—a screwdriver.

That spring, Manhattan was their playpen. They drank martinis at the Oak Room, daiquiris at the Waldorf, and champagne from the bottle at night in Central Park. They spent lazy afternoons in Chinese restaurants downtown, sipping lukewarm wine from water glasses filled with ice. Then they’d taxi through the Bowery to the South Street pier and feed seagulls crumbs of fortune cookies pulled from Marilyn’s purse.

Whether browsing antiques in Third Avenue shops or taking midnight dips in the park’s Bethesda fountain, it was a shared sense of play that bonded them both. “Everything was fun about Truman,” claimed his friend Eleanor Lambert. “He was like a precocious child, so cute and funny. He was able to bring people’s childhoods back to them.”

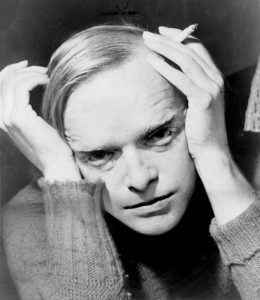

But Truman’s childlike qualities hid a baby-devil darkness. “He looks like a ten year old angel,” observed the French writer Colette, “but he’s ageless, and has a very wicked mind.” Truman lacked Marilyn’s gentle earnestness– you can see it in the photos of him lying supine, gazing at the camera like some puckish odalisque.  He gossiped. He put on airs. Ashamed of living out of a one bedroom basement, he pretended to own the whole Willow Street house. When friends came visit he’d give them a tour, showing off plans to “redecorate” or “refinish” the rooms.

He gossiped. He put on airs. Ashamed of living out of a one bedroom basement, he pretended to own the whole Willow Street house. When friends came visit he’d give them a tour, showing off plans to “redecorate” or “refinish” the rooms.

Where Truman shrank from his backwoods pedigree, Marilyn wore hers like a badge. She was rightly proud of overcoming her obstacles- the foster homes, the orphanage, the abuse that began as a child and continued into her starlet years. And when Truman longed to be “terribly rich” Marilyn “just wanted to be wonderful.”

She was wonderful, and Truman knew it. Between dancing and lunching and knocking back cocktails, he spent most of that summer glued to his typewriter clanging out a novella. The inspiration—a black frocked girl with a “soap and lemon cleanness,” a curvy mouth, upturned nose and saucer eyes of green-flecked blue. Her tussled hair cut like a boy’s, dyed in “ragbag” shades of light with “tawny streaks” and “strands of albino-blond and yellow.”

She scamped around the city in sunglasses and slips, full of nerves and insomnia and a stamped-out past. She drank bourbon to fight off the “mean reds,” she believed in self-improvement, she read horoscopes and Hemingway and William Somerset Maughn. She was Holly Golightly—Truman’s love letter to hope, New York City, and Marilyn Monroe.

ELIZABETH WINDER is the author of PAIN, PARTIES, WORK: Sylvia Plath in New York, Summer 1953. Her work has appeared in the Chicago Review, Antioch Review, American Letters, and other publications. She is a graduate of the College of William and Mary, and earned an MFA in creative writing from George Mason University.