by Jack Kelly

Benedict Arnold was one of the Revolutionary War’s most aggressive and courageous soldiers. It’s possible that without him, American patriots would have lost the Revolutionary War.

Yet Arnold was also our quintessential traitor. He did more than switch sides at a critical point in the war. He attempted, through deceit and subterfuge, to betray the American’s most strategic fort to the enemy. He then led British troops against his former comrades and burned the city of New London to the ground before decamping to England.

For two centuries historians struggled to make sense of this paradox. They simply could not accept, as a historian put it in 1913, “that we owe the salvation of our country at a critical juncture to one of the blackest traitors in history.” They fell back on the notion that Arnold had always had the soul of a blackguard, but had kept it hidden. From the beginning he had been motivated by self-interest and love of money. Even his childhood, the stories went, held clues to his lack of moral fiber.

More recent appraisals recognize that Arnold was indeed a paradoxical figure, as devoted to the patriot cause early in his military career as he was hostile to it later. Moreover, his contradictory character offers a valuable lesson in the complexity and perversity of history — and of human nature.

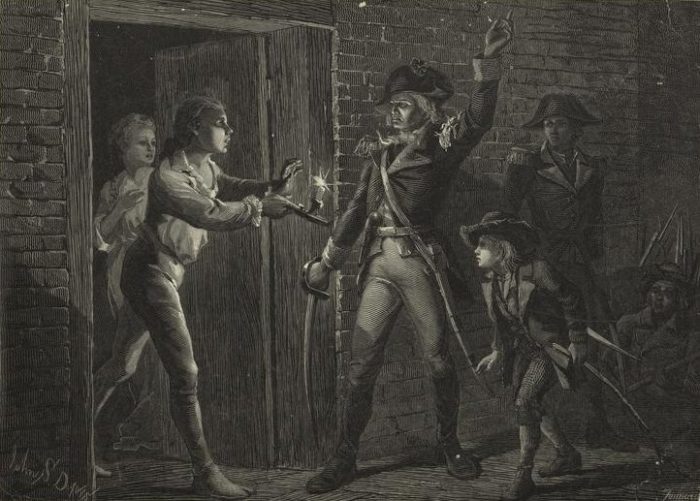

The details of Arnold’s betrayal are well known. Married to the daughter of a wealthy loyalist family, nursing resentments over the failure of Congress to reward his achievements, in 1780 he entered into a plot to hand over West Point to the British in return for a substantial sum of money. Only pure chance narrowly aborted the plot.

Less familiar are Arnold’s significant achievements during the first three years of the war. He displayed an uncanny ability to project authority and inspire the men he led. His intuitive grasp of military tactics and strategy rivaled that of more experienced officers.

After violence broke out at Lexington and Concord in the spring of 1775, Arnold was one of the enthusiastic military amateurs who answered the call to arms. A successful New Haven merchant and sea captain at the time, he joined in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, an important British post on Lake Champlain, the only inland water route from British Canada into the rebellious colonies.

Patriots eager to extend their revolution decided to go further and invade Canada. Arnold volunteered to lead a small army over the trackless mountains of Maine and surprise the city of Quebec. A herculean effort brought the intrepid leader and his men to within a hair’s breadth of taking the city. Arnold received a serious leg wound during a later assault on the fortress.

When British reinforcements arrived and the American effort collapsed, Arnold organized a more orderly withdrawal. Back at Fort Ticonderoga, he helped plan a strategy to stop, or at least delay, the British juggernaut.

During the summer of 1776, the British, relying on the expertise of the Royal Navy, assembled a powerful freshwater fleet in the north. Americans, under Arnold’s guidance, hammered together a small force of gunboats in the wilderness around Lake Champlain’s southern end. The object of the arms race was to delay the enemy long enough to close out the fighting season and postpone the confrontation for another year.

The strategy worked. The British spent the entire summer building ships to assert naval dominance over the narrow, hundred-mile-long waterway. Arnold, with his small pack of gunboats, hovered around the lake’s northern end in a daring show of force.

On October 11, 1776, the British finally set sail. Arnold met them in a small bay behind Valcour Island along the lake’s western shore. The tactic, which seemed suicidal, erupted into a wild, point-blank cannon battle that ended with the patriot fleet crippled and the British ready to deliver the coup de grâce the next morning. Somehow—historians still scratch their heads over it—Arnold and his men were able to escape through the British blockade and head south on the lake during the night.

There followed a frantic race, Arnold’s men rowing open boats through a sleet storm, the British slowly catching up. It culminated in another chaotic naval battle. Although Arnold lost almost his entire fleet, he was able to save most of his men. British commanders were so stunned by the patriots’ fanatical determination that they paused, thought it over, and returned to Canada.

The following year, when a British army did descend from Canada and take Fort Ticonderoga, the American patriots were better prepared. Under the leadership of Horatio Gates, they amassed a large force of continental soldiers and militiamen at Saratoga, north of Albany. Arnold played a significant role in the two battles fought there the autumn of 1777. He led a crucial charge during the climax of the second battle and was severely wounded. It would be the last time Arnold would fight for his country.

Three years later, all of Arnold’s heroic achievements—his extraordinary devotion to the cause, his disbursement of his own money to pay his troops, his war wounds—descended into the black hole of his infamous betrayal. His name became synonymous with traitor.

Arnold’s paradoxical nature gives him new relevance in an era when many have questioned whether the members of the founding generation should be venerated or reviled. Could a leader of the Revolution be both a rich man and an advocate for an egalitarian republic? Could a slave owner promote the principle that all men are created equal? Could a man grab land from indigenous people and still contribute to forging a durable, democratic nation?

The focus on the flaws of the founders has been a necessary and important corrective to two centuries of lionization. But Arnold’s paradoxical nature reminds us that all men and women contain contradictions. Our judgment must be proportional—honor for his achievement, condemnation for his treason.

Washington, Jefferson, and Madison all owned slaves. If that was their sole attribute, we could dismiss them as petty and culpable figures. But within each was a paradox. They created a country which overturned the subservience of citizens to monarchs, a country that moved, far too haltingly, in the direction of individual liberty, human rights, and justice.

No one is for placing a traitor on a pedestal. But if we can accept that Benedict Arnold helped us win our independence and betrayed his comrades and his country, then we can see more clearly that history is inevitably shaped by flawed and conflicted human beings.

Jack Kelly is an award-winning author and historian. His books include Valcour: The 1776 Campaign That Saved the Cause of Liberty and Band of Giants: The Amateur Soldiers Who Won America’s Independence, which received the DAR History Medal. He is also the author of The Edge of Anarchy, Heaven’s Ditch, and Gunpowder and is a New York Foundation for the Arts fellow in Nonfiction Literature. Kelly has appeared on The History Channel, National Public Radio, and C-Span. He lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.