WCAG Heading

by Tom Clavin

August 29th is the anniversary of the discovery of Ishi. No, this is not an island or one of Jupiter’s moons. At the time when Ishi was found, on August 29, 1911, he was touted as the last “Stone Age Indian” in the United States. Many years later some doubt was cast on that, but for the rest of his life and afterward, Ishi was believed to be the last “pure-blood” Native American left. After centuries of genocide and disease that had nearly eradicated the indigenous population of the U.S., Ishi was viewed as the last of his kind.

He was born in 1861, a member of the Yahi tribe. Prior to the California Gold Rush, which began in 1848, the Yahi population was around 400. When Ishi was four, his family was involved in the Three Knolls Massacre, in which 40 of their tribesmen were killed. Although 33 Yahi managed to escape, cattlemen killed about half of the survivors. Those who remained, including Ishi and a few family members, went into hiding for the next 44 years.

The gold rush had brought tens of thousands of miners and settlers to northern California, putting pressure on native populations. Gold mining damaged water supplies and killed fish and the deer left the area. The settlers brought new infectious diseases such as measles and smallpox. The northern Yana tribe became extinct while the Yahi population dropped dramatically. Searching for food, they came into conflict with settlers, who set bounties of 50 cents per scalp and $5 per head on the natives. The Three Knolls Massacre was one of several genocide events in the California Indian Wars. These were a series of wars, battles, and massacres between the combined forces of U.S. Army and the California State Militia, especially during the early 1850s, and the indigenous peoples of the state. The wars lasted from 1850, immediately after California became a state, to 1880.

In 1879, the federal government started Indian boarding schools in California, furthering the assimilation of the tribes. Some men from the reservations became renegades in the hills. To hunt them down over the years, volunteers among the settlers and military troops carried out additional campaigns against the northern California Indian tribes. While all this was going on, Ishi had been growing up, in hiding.

In late 1908, a group of surveyors came across the camp inhabited by a middle-aged man and woman, and two older people. These were Ishi and his younger sister, his uncle, and his mother. Three fled while the latter hid in blankets to avoid detection, as she was sick and unable to run. The surveyors ransacked the camp, and Ishi’s mother died soon after his return to the camp. His sister and uncle never returned. Ishi continued to hide out in the hills, living off what the land provided.

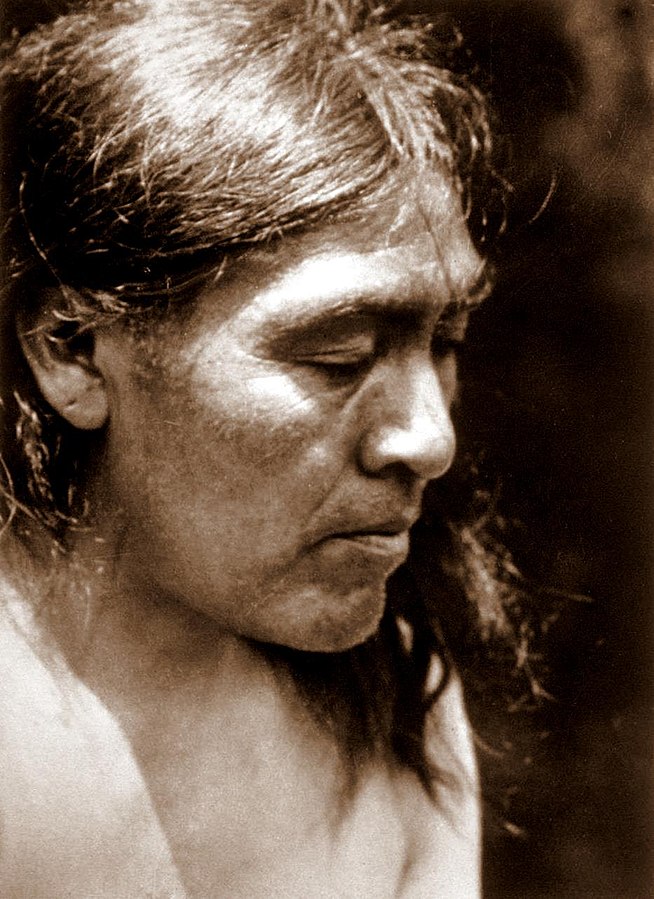

By the summer of 1911, all other members of the Yahi tribe, including Ishi’s family, had died. On that August 29, he was cornered by dogs outside the town of Oroville. While holding Ishi in the local jail, town officials had the presence of mind to reach out to the Hearst Museum, then known as the University of California Museum of Anthropology. Following custom, Ishi refused to speak his name to outsiders without introduction by someone from his tribe, but there was no one left. Soon, at least, he would be referred to by the word that means “man” in the Yahi language. Ishi was then about 60 years old.

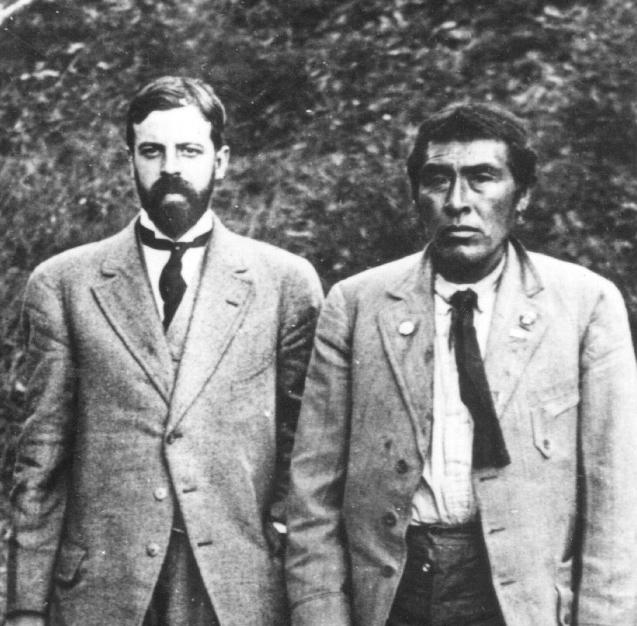

The director of the Hearts Museum, Alfred L. Kroeber, proposed that Ishi live at the museum as an alternative to the plan to relocate him to a reservation in Oklahoma. Within days, Ishi was brought to the museum’s first location in San Francisco, near Golden Gate Park, where he lived for the last four and a half years of his life.

Publicized as “the last wild Indian in California,” Ishi was employed at the museum to demonstrate Yahi culture. He spent much of his time on display for white museum audiences, fashioning obsidian and colored glass projectile points and recording Yahi songs and stories. To this day, the museum has in its collection the objects and recordings that Ishi made.

Ishi also worked as a live-in custodian and research assistant at the museum. In the summer of 1914, at Kroeber’s insistence, Ishi reluctantly traveled with anthropologists back to his home and the site of his family’s massacre, the Deer Creek Valley area of Tehama County, to document Yahi culture.

Ishi was known throughout San Francisco and could be found hunting on Mount Parnassus and walking in Golden Gate Park. Many described Ishi as surprisingly friendly and eager to share his knowledge. Today, Ishi’s position at the Hearst Museum would probably be considered indentured servitude. Kroeber counted Ishi as his friend, but he also used their unequal relationship to advance his own career and the museum’s popularity.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Ishi passed away in March 1916 from tuberculosis, which at the time was sweeping through San Francisco. What happened next is rather sad.

During his time at the museum, Ishi was apparently very distressed to be living amidst the remains of Native American ancestors unearthed for research and curation. A dying wish was that his own body be cremated according to Yahi tradition. Disregarding this, a doctor at the university performed an autopsy on his body. Kroeber, traveling at the time of Ishi’s death, had advised against this. Still, returning to Berkeley after the autopsy’s completion, he sent Ishi’s brain to the Smithsonian Institution for further study. Ishi’s body was finally cremated and placed in a niche at a cemetery just south of San Francisco.

Ishi’s brain remained at the Smithsonian for over 80 years. In 2000, as the result of efforts by the Maidu, Redding, and Pitt River tribes in California, his ashes and brain were repatriated and reunited. Ishi is now buried in a secret location in the Deer Creek Valley, where presumably they cannot be disturbed.

Originally published on Tom Clavin’s The Overlook.

Tom Clavin is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include the bestselling Frontier Lawmen trilogy—Wild Bill, Dodge City, and Tombstone—and Blood and Treasure with Bob Drury. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.