by Tom Clavin

151 years ago, a journey to Africa began that would garner international fame. In March, Henry Morton Stanley set out from Zanzibar to find a missing British explorer. The intrepid Stanley would always be remembered for this adventure…but often overlooked was one he had a few years earlier with a soon-to-be iconic American gunfighter.

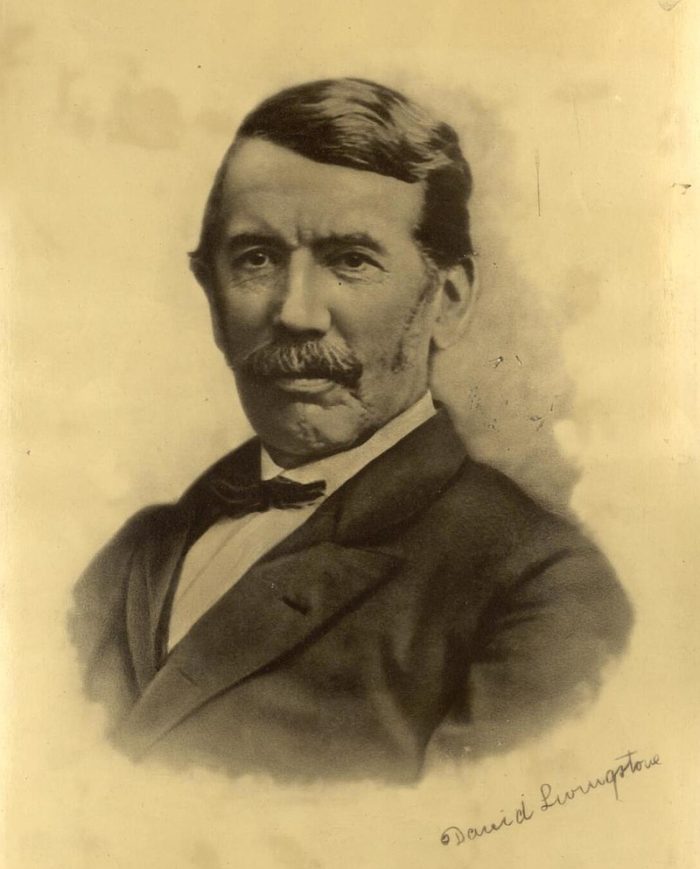

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Stanley had been born as John Rowlands in January 1841 in Wales. Orphaned very young, he lived in a variety of homes in England including a workhouse for the poor. He managed to make his way to New Orleans and was taken under the wing of Henry Hope Stanley. The wealthy trader cared for the teenager until the outbreak of the Civil War when he joined the Confederate Army, as Henry Morton Stanley. He was captured during the Battle of Shiloh in 1862, was released when he agreed to join the Union Army, then was released to join the U.S. Navy, serving on the USS Minnesota. (He has the distinction of being the only man during the Civil War who served in those three military forces.)

After the war, Stanley opted to organize an expedition into the Ottoman Empire, which turned out to be a bad decision when he was captured and tossed into prison. The Welshman/Southerner had a silver tongue, though, and he charmed Ottoman officials enough that they set him free. He next was in New York, where he found a job as a newspaper reporter.

Let’s fast-forward: Dr. David Livingstone was really missing. Already well-known as an explorer in his native Great Britain, in August 1865 he had begun an expedition to find the source of the Nile River. He had planned on this journey taking two years. Almost six years later, there was still no word from Dr. Livingstone. Stanley’s employer, James Gordon Bennett Jr., editor of The New York Herald, thought it would be a great story if his top globe-trotting reporter found out what had happened to Dr. Livingstone and brought back proof of his death. Surely, by now, he had to be dead, yes? In March 1871, having arrived from New York, Stanley tugged on his hiking boots and began walking toward Lake Tanganyika.

Remarkably, Stanley not only found Dr. Livingstone but found him alive. Somewhere along the way, the explorer’s search had gotten derailed and Stanley found him sick and broke in the village of Ujiji, where he had been living at the mercy of Arab slave traders. Entering the village, Stanley spied an older white man with a gray beard. He walked toward him with an outstretched hand and said, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume.” As we now know, this became a rather famous quote.

Oddly, Dr. Livingstone refused to return to Great Britain with Stanley. Instead, he remained in Africa, and 18 months later he died in what is today Zambia. He finally did go back home, for burial in Westminster Abbey.

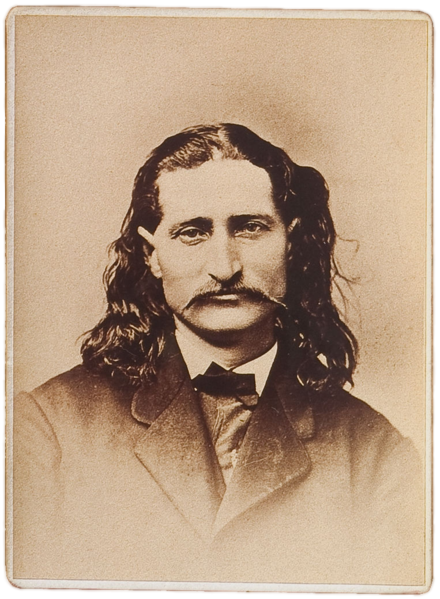

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

What of that American gunfighter? Several years before Stanley’s African adventure, in 1867, while in New York he had read an article in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine by George Ward Nichols about a gunfighter on the frontier named “William Hitchcock” and called Wild Bill (whose real name was James Butler Hickok). Fascinated by the article and the larger topic of the post-war expanding frontier, Stanley, with Bennett’s blessing, set off for Kansas.

He found Hickok, who had just turned 30, at Fort Riley. The restless frontiersman and the restless reporter hit it off immediately. The fort compound housed several sutler’s shops that provided liquid refreshment, and the two men frequented them together. They told tales of their most interesting experiences, including during the Civil War—and some of them were probably true. By this time in his life, and having digested the sensationalized Nichols article, the line between fact and fiction was becoming thinner and thinner for Wild Bill.

Stanley was a more fascinated listener than a fact-checker. In an article Stanley wrote for The Herald, he reported that he had asked Hickok how many white men he had killed “to your certain knowledge.” After seeming to give the question some thought, Hickok replied, “I suppose I killed considerably over a hundred.” Stanley marveled at the number and wondered if there had been good reasons for all those fatalities. Hickok assured him that he “never killed one man without good cause.”

With Stanley’s article of tall tales appearing in the popular Herald only a few months after the Harper’s opus, and with no other frontiersman gaining a similar amount of attention, Wild Bill Hickok was further solidified in the minds of folks back east as the American westerner. He represented the men who were busy blazing trails and defying “savages” so that Manifest Destiny could be fulfilled.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

There were plenty of adventures in Stanley’s life in addition to his Hickok and Livingstone encounters. He rode as a special correspondent with a British force sent to topple Tewodros II of Ethiopia, he was the first to tell the world of the fall of Magdala in 1868, he covered a civil war in Spain, and more. In his later years, and back in England, he married the Welsh artist Dorothy Tennant. They adopted a child named Denzil, who was the son of one of Stanley’s first cousins, though Stanley concealed this fact from the public and possibly even from Dorothy.

Mainly at his wife’s behest, Stanley entered Parliament as a Liberal Unionist member for Lambeth North, serving from 1895 to 1900. He disliked politics and made little impression on Parliament. He became Sir Henry Morton Stanley when he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the 1899 Birthday Honors, in recognition of his service to the British Empire in Africa. Stanley died at his home in London in May 1904. His grave is in the churchyard of St. Michael and All Angels’ Church, marked by a large piece of granite inscribed with the words “Henry Morton Stanley, Bula Matari, 1841–1904, Africa.” Bula Matari translates as “Breaker of Rocks” or “Breakstones” and was Stanley’s name among locals in Congo.

Oh, and for you classic movie aficionados, Stanley was portrayed by Spencer Tracy in the 1939 feature Stanley and Livingstone. Extra credit to those who recall that Dr. Livingstone was played by Cedric Hardwicke.

Originally published on Tom Clavin’s The Overlook.

Tom Clavin is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include the bestselling Frontier Lawmen trilogy—Wild Bill, Dodge City, and Tombstone—and Blood and Treasure with Bob Drury. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.