by Buddy Levy

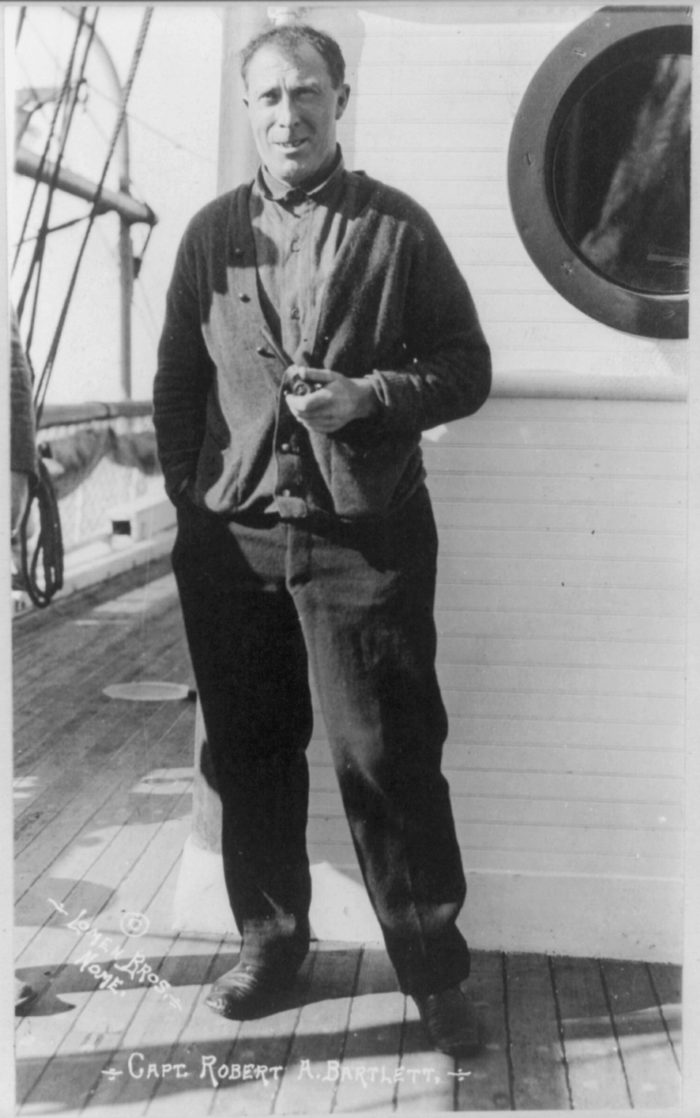

Empire of Ice and Stone by Buddy Levy is the true, harrowing story of the ill-fated 1913 Canadian Arctic Expedition. The following excerpt introduces Captain Bob Bartlett, a legendary adventurer and one of the two men who would come to define the expedition.

Captain Robert “Bob” Bartlett, standing on the steps of the front porch of Hawthorne Cottage, took the telegram from his father. He’d just returned from a lengthy and unsuccessful sealing voyage, and already he was restless. Their cottage was comfortable, certainly, and it was good to be with family again. His parents were both nearing seventy, and they could use his help. But it didn’t do to be idle, to remain landlocked for long. Strong spring winds blew in from the Labrador Sea, raising whitecaps on Conception Bay and rattling the eaves of the cottages in the little fishing village at the far easterly fringe of North America.

Bob Bartlett’s ancestors had skippered ships in the seal and cod fisheries for generations. The famous Bartletts of Brigus were involved in exploration as well. In 1869, his uncles John and Sam, and his father, William—as captain, first mate, and second mate, respectively—took polar explorer Dr. Isaac Hayes above the Arctic Circle, north as far as the treacherous Melville Bay on the Greenland shores, vainly searching for traces of Sir John Franklin’s vanished expedition of 1845. His great-uncle Isaac Bartlett was captain of the Tigress in 1874 on the rescue mission searching for Charles Francis Hall’s lost USS Polaris. He discovered survivors of that shipwreck on a moving raft of ice in the lower reaches of Baffin Bay. They’d been adrift for nearly two hundred days, and yet not one of them had died. Bob Bartlett’s great-uncle returned to a hero’s welcome.

Seagoing adventure was in Bob Bartlett’s blood. Throughout his childhood and teens, on summer vacations from school, he’d joined his father on sealing voyages. At seventeen he commanded his first schooner, the Osprey, returning from the rough Labrador waters with his cargo holds bursting with cod. By then he’d been studying for two years at the Methodist College at St. John’s, his mother having sent him there with the hope that her eldest son would become a minister. But the thrill of the wind-filled sails, of salt spray washing over the rails, the sight of an open, endless horizon—their draw proved too alluring. He’d tried his best, and though he was an excellent student, he knew the only classroom for him was the next ship, the next sea voyage. He yearned to be, like his father and uncles, a master mariner. But Newfoundland strictly regulated such titles, requiring four years at sea to become second mate, another year to make first mate, and a sixth year, culminating with arduous examination in Halifax, to make master.

Bartlett would later explain his decision to quit school and follow his heart in nautical terms: “I held the tack as long as I could, and then came about, eased off, and ran before the wind of what I was meant to do.”

That wind took him, at eighteen, on his first long voyage as a hired seaman aboard the Corisande, bound for Brazil carrying a shipment of dried cod. He spent the next six years almost entirely aboard one ship or another: on cod and sealing vessels in the Labrador waters in spring and summer, on merchant ships every fall and winter. He sailed south to the Caribbean and Latin America on runs for bananas and other tropical fruits scarce in the North; he sailed across the North Atlantic and through the Strait of Gibraltar to the Mediterranean Sea, visiting some of Europe’s most vital and vibrant port cities. By 1898, at the age of just twenty-three, he’d passed his written and technical exams and now possessed the right and privilege to command a ship anywhere in the world. His papers also gave him the hard-earned title reserved for those rare men who had the stuff to spend their lives at the ship’s wheel or in the crow’s nest: captain and master mariner.

Captain Bob Bartlett weighed his options. He could command a fishing or merchant vessel, but he yearned for something new, something different and more challenging. He did not have to wait long. In July of 1898, his uncle John Bartlett came to him with a tantalizing offer. The uncle had been asked to captain the Windward, the 320-ton flagship of American Robert Peary’s first North Pole expedition. The plan was to sail from New York north clear through the Davis Strait and Smith Sound, aiming as far north between Greenland and Canada’s Ellesmere Island as they could go before they were iced in. After that, Peary aimed to strike out with dogsled teams and go on snowshoes the remaining four or five hundred miles to the North Pole. Uncle John invited his nephew Bob to come along. It promised to be one hell of an adventure.

Bob Bartlett agreed on the spot. This was the beginning of ten years of Arctic service and three attempts at the North Pole alongside the inimitable, complex, and controversial Robert Peary.

The 1898 voyage offered enough excitement and drama for an ordinary person’s lifetime, but Bob Bartlett—even in his early twenties— was hardly ordinary. The Windward became stuck fast in the ice north of Cape Sabine, where, in 1884, Commander Adolphus Greely and his party of twenty-five men had fought starvation and one another during a dark, dreadful, and tragic winter. From the deck of the Windward, Bartlett could see the barren, fatal shores of Ellesmere Island and, to the east, twenty-five miles across the Smith Sound, the mountainous Greenland coastline. He was learning about life above the Arctic Circle, about the capricious mercies of sea ice.

Since Peary knew that the Windward would remain icebound until the following spring, he left Bartlett and most of the crew and struck out through December’s polar darkness with two dogsled teams to see how far north he could go. They plowed through blizzards and temperatures plunging to −50ºF, camping on the ice and sometimes building igloos. He made it as far as Fort Conger, the barracks and base Greely had established at Lady Franklin Bay on northern Ellesmere Island almost twenty years before. But by the time he reached those long-abandoned dwellings, his feet were severely frostbitten, and as they thawed in the warmth of the wooden shelter, they became gangrenous. After a time, he realized his feet would not improve, and he ordered his men to lash him onto a sled and return to the Windward, two hundred miles to the south.

When Peary returned in March of 1899, having been gone almost three months, Bartlett helped to lay him out for surgery on the Windward’s cabin table. Bartlett then assisted the ship’s doctor, administering the ether Peary would need for the operation. The skin of his toes had sloughed off almost entirely, the necrotic flesh black and blistered. The doctor amputated eight of his toes. Before long, Peary was up and hobbling around on crutches, eager to start exploring again. Through the whole ordeal, he’d never uttered a word of complaint. Bartlett, deeply impressed by Peary’s toughness, asked him how he managed to stand the pain.

Peary just looked up and said stoically, “One can get used to anything, Bartlett.”

Copyright © 2022 by Buddy Levy

Buddy Levy is the author of more than half a dozen books, including Labyrinth of Ice: The Triumphant and Tragic Greely Polar Expedition; Conquistador: Hernán Cortés, King Montezuma, and the Last Stand of the Aztecs; River of Darkness: Francisco Orellana’s Voyage of Death and Discovery Down the Amazon. He is co-author of No Barriers: A Blind Man’s Journey to Kayak the Grand Canyon and Geronimo: Leadership Strategies of an American Warrior. His books have been published in eight languages. He lives in Idaho.