Ellen Wayland-Smith

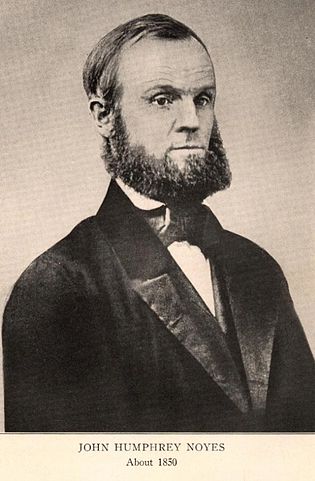

A Minister Is Born: John Humphrey Noyes

When John Humphrey Noyes’s mother, Polly Hayes Noyes, took a deep breath after the travail of childbirth to see that her firstborn son was a “proper child”—that is, one apparently hearty enough to buck the odds of making it through the bitter New England winter to see his first birthday—she prayed on the spot that he might become a “minister of the everlasting gospel.” Polly Hayes Noyes’s prayer would be granted twenty-two years later, in 1833, when John Humphrey received his minister’s license from the Yale Theological Seminary. But on the day of his birth, as Polly Hayes Noyes fell back upon her pillows in sweet exhaustion, this prim and conventional Congregationalist could hardly have anticipated the theological edifice her infant son would one day construct.

For John Humphrey Noyes would not become just any minister; his brainchild, the Oneida Community, would blend a utopian ethic of total selflessness, communism of property, and divinely sanctioned free love into one of the most baroque interpretations of Jesus’ “everlasting gospel” ever attempted.

Born into a prosperous New England family in Brattleboro, Vermont, on September 3, 1811, John Humphrey Noyes was the fourth of nine children. Polly Hayes Noyes was a strong-minded, deeply religious woman who demanded that matters of spirituality be kept foremost in the raising of her children. John Humphrey Noyes’s father, John Noyes Sr., was of a more secular character; a 1795 graduate of Dartmouth College, John was first a teacher and then a successful Brattleboro businessman, spending a two-year stint as a representative in Congress from 1815 to 1817. Letters that John Humphrey Noyes wrote home to his wife from Washington in 1815 hint at his enjoyment of the city’s cosmopolitan privileges, foreign to the native Vermonter: “The style and manner of proceeding, the dignity which every member seems to feel, and the living at our quarters, all are very, very different from what we have in Vermont. A man cannot but feel animated, and as it were elevated.” “We live full well enough for our health,” he continued later in the same letter. “Our meat and poultry are of the first quality.… Brandy and wine very good and very dear. Plenty of oysters, apples, chestnuts.” While he was gallant (or cagey) enough to write to his wife that the “pie, apples, and the wine lost their charms” when he thought of the comforts of home, one senses the sensual enjoyment he took in “the bustle, the show and parade of great folks.” Later in life, he would become a rather pronounced alcoholic; only when he received a formal written letter from his wife and children begging him to cease “indulging [his] degrading appetite” was he jarred from his pleasures.

“In the highways and byways of business he was a born Solomon,” John Humphrey would later recall of his father, one who “in social and commercial life … found his natural sphere.” The competing claims of religion and a worldly life were twin currents traversing the Noyes household. “Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth,” warns the apostle Matthew, “where moth and rust doth corrupt, and thieves break through and steal,” but, rather, “Lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven” (Matthew 6: 19–21). Flying in the face of the good evangelist, John Humphrey Noyes would devote his life to brokering a fragile truce between treasures on earth and those in heaven. Perhaps only the collision of two such vigorously opposed natures as the saintly Polly Hayes Noyes and the carnal John Noyes Sr. could have spawned a compromise as brilliantly bizarre as John Humphrey Noyes, who would close this parental gap between spirit and flesh by claiming, among other things, that the sexual organs were the “first and best channel of the life and love of God” and that getting salvation was “a business—like getting a living”—in other words, that spiritual and earthly pursuits were, in fact, one and the same thing.

Young John was a thoughtful boy—as a child, he was fond of going to bed early because “he wanted to think”—and from the first a natural leader. As his mother recalled in later years, “I can see him now marching off up the hill at the head of a company of his playmates, all armed with mullein stalks.” Sent away to school in Amherst, Massachusetts, when he was nine years old, John Humphrey Nyes sent letters home that reveal a boy seized by homesickness but anxious not to upset his mother on his account: “Mamma, I must say that when I am not reading, or writing, or studying, I am homesick. Yes, I am homesick.… But away with all this! I fear I have distressed you already.… Tell Papa that I am studying Cicero, and that I have got to the fourth book of Virgil.” When he was ten years old, his family relocated to the village of Putney, Vermont, within easy communication of his new school, Brattleboro Academy, where John would complete his preparation for college. Endowed with a ruddy, freckled complexion and a bright red shock of hair, John Humphrey Noyes early gave signs of a passionate nature to match; a friend from his Brattleboro days referred to him as “inclined to give way a little too much to the libido corporis.”

Just which “lusts” of the body the young boy had a particular weakness for is not divulged in the friend’s letter; it is clear from his diaries that, by the time John Humphrey had entered Dartmouth College as a freshman in 1826, a partiality for the ladies was chief among them. This journal, begun at the age of eighteen in 1829, provides glimpses of a teenager struggling with paralyzing shyness in his relations with the opposite sex. He was further hampered by the conviction that his red hair and freckles rendered him physically repulsive. John Humphrey compared himself to the “Black Dwarf” in the Walter Scott romance of the same name, a tortured, loveless figure whose deformed body and “long matted red hair” forced him to sequester himself in the forest as a hermit. The young collegian’s interactions with women were, accordingly, nothing short of torture. In one diary entry, he berates himself: “Oh! For a brazen front and nerves of steel! I swear by Jove, I will be impudent! So unreasonable and excessive is my bashfulness that I fully believe I could face a battery of cannon with less trepidation than I could a room full of ladies with whom I was unacquainted.”

Despite his best resolutions, John Humphrey continued to experience acute anxiety and embarrassment in social situations. Once, at a wedding party, he mistook the name of a lady he was introducing to a company of gentlemen; he recorded afterward that he could “feel [his] cheek burn with shame” upon recollecting the “scornful smile [that passed] over the countenance of a certain lady” who, sitting near, overheard his blunder. A sense of intense social shame and self-loathing, especially when he felt himself caught in the gaze of the opposite sex, was one of the strongest currents in young Noyes’s emotional life. At one point, he had even resigned himself to remaining unmarried and becoming a philosopher, renouncing the physical world for the life of the mind.

Ellen Wayland-Smith teaches in the Writing Program at the University of Southern California, and received her PhD. in Comparative Literature from Princeton University. A descendant of John Humphrey Noyes, the founder of the Oneida community, she lives in Los Angeles with her family. Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table is her first book.