by Stephen Solomon

Paul Revere: The Silver Smith

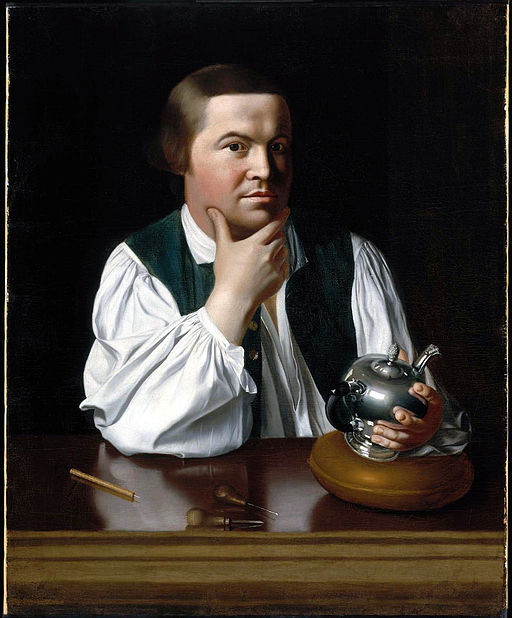

When John Singleton Copley painted a portrait of Paul Revere in 1768, he depicted an idealized image of one of Boston’s leading artisans. Revere, then in his mid-thirties, sits behind a polished table that shows none of the scars and discolorations of an artisan’s workbench. He is dressed informally in an open, full-sleeved white linen shirt with a blue-green waistcoat that he left unbuttoned. He cradles his chin in his right hand, while his left holds a round teapot whose surface is smooth and unadorned, awaiting the finishing decorations. His engraving tools lie at his elbow and ready to use.

Paul Revere was poised that year, 1768, to begin participating in the activities that would lift him into the orbit of the best-known patriots of the Revolutionary period. Still seven years ahead of him was the midnight ride to Lexington to warn of the march of British troops out of Boston the ride immortalized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s now familiar line, “Listen, my children, and you shall hear, of the midnight ride of Paul Revere . . .” Important though the ride was, it was the delicate-looking engraver’s tools depicted in Copley’s portrait that would define Paul Revere’s most vital contribution to the patriot cause. The engraving tools look much like pens, and Revere used them to make political cartoons that circulated widely and that proved as effective as written words.

Paul Revere’s skills in copper and silver owed much to his father’s influence. Apollos Rivoire had come to America in 1715 after boarding a ship in the harbor of Saint Peter Port in Guernsey, an island in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy. Dropped off by his uncle at the dock, Rivoire surely felt the profound uncertainty of what lay ahead of him. Less than a week from his thirteenth birthday, he was embarking alone on an uncertain journey across the ocean to Boston, where he would try to make a go of it without much more than his own adolescent bravado to guide him. The young Rivoire landed in Boston and took up an apprenticeship with a local silversmith. When the silversmith died seven years later, Rivoire bought freedom from his indenture and set up his own shop.

He changed his name from Rivoire to Revere to make it easier for the local people to pronounce and married the daughter of a Boston merchant. Paul Revere, his son, was born in 1734 and grew up on the narrow crooked streets of the North End. The water that lapped at the docks just a few blocks away made an overpowering allure. Young boys like Paul spent much of their free time playing as the dockworkers unloaded the heavy cargo. They dove off the wharves into the cold water of the bay and climbed into the riggings of the sailing ships. More serious business called them as well. The young Revere served as an apprentice to his father, watching him use hammers to pound silver until it took the finished shape of cups and spoons.

Gradually, he learned how to work with silver, copper, and brass. Paul went to the North Writing School, a two-story school building where boys destined for the artisan trades received the most basic education, learning writing on one floor and reading on the other.

Paul proved as self-reliant as his father, too. At just nineteen, he inherited the business and supported his family when Apollos died. Gradually over the years, Revere acquired the connections that would make him familiar in colonial politics. He served in the militia during the French and Indian War, and his growing reputation as a skilled silversmith attracted attention. Revere saw his business prosper, and he came to know more and more of the Boston radicals like Samuel Adams as his customers.

He made connections at the New Brick Church, where he went on the Sabbath, and on various civic committees. Gradually, Paul Revere moved into the ranks of the radicals themselves. He joined them for drinks at the Salutation Inn and often retired to a private room used for meetings of the North Caucus, a group of Whig activists whose membership counted many artisans and seamen. Along with a few other such groups, they discussed political affairs and put forward candidates for election at the Boston town meetings. Samuel Adams and John Adams were members.

Paul Revere’s immersion into politics deepened in 1765 as he joined the Sons of Liberty in its protest against the Stamp Act. Again and again, he contributed his special talents as a silversmith to the cause of liberty. In 1766, when it repealed the Stamp Act, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act asserting its power to enact tax and other laws over the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” The following year, Parliament began passing the Townshend Acts to raise revenue by imposing duties on goods imported to America such as tea, paper, paint, and glass. The Massachusetts House of Representatives sent its Circular Letter, written by Samuel Adams, to the other colonial assemblies in 1768, asking them to join Massachusetts in opposing the new taxes. Acting on instructions from London, Massachusetts governor Francis Bernard ordered the assembly to rescind the letter or he would dissolve the body. When the lawmakers refused to rescind by a vote of ninety-two to seventeen, Bernard carried out his threat.

The assembly’s refusal to rescind the Circular Letter caused a sensation in Boston and throughout the colonies. And it motivated Paul Revere to turn his considerable skills as an engraver and silversmith to help the colonial cause. Commissioned by the Sons of Liberty, Revere celebrated the ninety-two lawmakers by making a silver punch-bowl in their honor—the Sons of Liberty Bowl that would become an American national treasure.

Paul Revere engraved on the bowl the names of fifteen Sons as well as an inscription to John Wilkes, the British member of Parliament who was a hero in the colonies because he was jailed on charges of seditious libel for criticizing the king. Around the sides of the bowl he engraved a variety of decorative elements, including a liberty cap, flags, references to the Magna Carta and the (English) Bill of Rights, and an inscription to the lawmakers “who, undaunted by the insolent Menaces of Villains in Power . . . Voted not to rescind.”

Paul Revere was not finished. He had plenty of venom for the remainder of the lawmakers, those who had complied with Bernard’s demand to rescind the Circular Letter. On a copper plate he engraved a political cartoon for printing and distribution far and wide. Calling the engraving “A Warm Place—Hell,” Revere heaped scorn on the rescinders. Two devils with pitchforks prod the lawmakers into the cavernous jaws of a fearsome dragon that breathes fire and represents the Puritan idea of a forbidding Hell. A snake writhes at their feet. The engraving makes some of the rescinders, who are dressed in colonial garb, identifiable to citizens of Boston.

At the bottom of the engraving is a stanza: “On brave rescinders! To yon yawning Cell, seventeen such Miscreants will startle Hell.”

Many years later, when he had reached the age of eighty, Paul Revere remembered that he had done the engraving when he “was a young man, zealous in the cause of liberty when he sketched it.”

STEPHEN D. SOLOMON is the author of REVOLUTIONARY DISSENT: How the Founding Generation Created the Freedom of Speech and an associate professor at the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at New York University. A graduate of Georgetown University Law Center, he teaches First Amendment law to graduate and undergraduate students. He has written for numerous national publications including The New York Times Magazine, Fortune, and The New Republic, and has been recognized with the Gerald Loeb Award and the Hillman Prize. His last book, Ellery’s Protest, told the story of the Supreme Court’s controversial decision forbidding state-sponsored prayer and Bible reading in public schools.