by Greg King and Penny Wilson

A grim, glowering fortress loomed in the darkness, bathed in the glow of arc lights shadowing its battlements and towers. This was the Illinois State Penitentiary at Joliet, thirtyish miles south of Chicago. Convicted killers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb first saw it on the night of September 11, 1924. Found guilty of the kidnapping and murder of fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks, the pair had escaped the death penalty through the specialized skills of attorney Clarence Darrow only to find themselves condemned to life imprisonment.

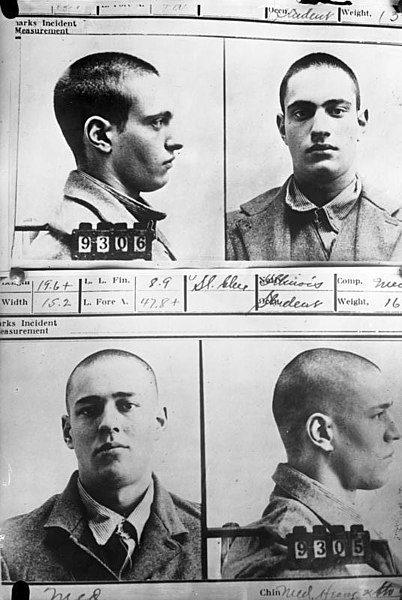

Leopold and Loeb had stunned Jazz Age Chicago. The Bobby Franks murder was the original “Crime of the Century,” conceived and carried out solely for the thrill of it. Leopold and Loeb, sons of millionaires, had lacked for nothing: mansions, automobiles, stylish clothing, considerable bank accounts. As courtroom arguments played out, they had used family money to soften their stay at the Cook County Jail, but this indulgence ended in Joliet. Abruptly, the pair were introduced to their new life. Their heads were shaved; they were photographed and fingerprinted; authorities assigned them prison numbers: Leopold was Inmate No. 9305, and Loeb No. 9306. After processing, they were hurried to their separate cells, disappearing into the penitentiary population.

On Leopold and Loeb’s arrival, the Illinois State Penitentiary was already out of date and seriously overcrowded. For two decades, it had been condemned as unfit for habitation, yet it continued to operate. Built in 1858 of limestone quarried on the site by prisoners, it was meant to house 900 inmates; by 1924 over 1,800 prisoners were incarcerated behind its grim walls. The cells, four feet by eight, were damp, had narrow windows, and possessed no plumbing: prisoners were given a jug of water each morning and made do with a bucket to use as a toilet.

Every aspect of life at Joliet was regulated. Leopold and Loeb were given two changes of underwear, blue shirts, pants, socks, and heavy shoes to use each week. Contact with the outside world was limited. They could send a single letter and receive visitors every second week. Using funds from their prison accounts, they could purchase tobacco, rolling papers, chewing gum, and candy from the prison commissary. There were no other privileges.

A bell awoke prisoners at 6:30 AM and the cell blocks filled with sounds of locks opening, doors slamming shut, and boots marching along the steel flooring. After dressing, inmates grabbed the buckets and carried them into the courtyard, emptying their refuse into a rancid trough. Meals were served in a large dining hall; twice a week prisoners had beef stew for breakfast; other days hash was served. The food was cold and unappealing, sitting in pools of congealed fat on aluminum trays.

Leopold and Loeb spent most of their days working in prison shops: Leopold wove rattan chair bottoms, while Loeb constructed furniture. Between meals, they were allowed two fifteen-minute breaks in which to walk or smoke. After dinner at four, they returned to their cells. At nine, lights were extinguished.

Having come from privilege, Leopold and Loeb struggled to adjust to their new lives. A Chicago Tribune reporter visited in the weeks after they arrived at Joliet and wrote that “the prisoners are slowly reaching the edge of despair. Loeb holds up better than Leopold, it is said.” This statement was true. Nathan hated the food and had his relatives bring him lobster, crab, and chicken when visiting. With his cold, brittle personality, Leopold found no friends and kept to himself. His superior attitude rankled his fellow inmates, and most treated him with disdain. Loeb, a chameleon, was better able to adapt and made friends easily. “People who knew Dick Loeb” in prison, wrote one reporter, “are almost unanimous in remembering him as an extraordinarily attractive young man.” Loeb was never once caught violating prison rules and he was never disciplined for any reason: officials assigned him the highest prisoner rank: “Grade A,” singling him out as exceptionally trustworthy, cooperative, and obedient.

Attribution: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-12794 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

In 1925, a new facility, Stateville Penitentiary, opened a few miles away. In May of that year, after a bout of appendicitis, Leopold was transferred there because it had modern medical facilities. At Statesville, he helped organize the prison library, but his frequent violation of prison rules, won him repeated stints in solitary confinement.

Loeb remained at Joliet and kept in minimal contact with Leopold. “Once in a great while,” Leopold wrote, “I would get a message from Dick in the old prison. Usually, these were merely short verbal messages, little more than hellos.” The relationship between the pair, always frantic and furious, was fraught with more than a little distrust and barely disguised antipathy, though passing time brought them back together in a new endeavor.

Transferred to Statesville in 1930, Loeb established a prison school for inmates, and eventually, Leopold joined him in teaching classes and correcting papers. The school was a huge success, and the program was expanded to prisoners at Joliet, becoming a crowning achievement for the Illinois prison system.

In January 1936, Loeb was slashed to death by a fellow inmate who claimed that Richard had made unwanted sexual advances toward him. Leopold remained at Stateville until his parole in 1958. He disappeared into relative obscurity in Puerto Rico, though his name made headlines again when he unsuccessfully sued author Meyer Levin over his novel Compulsion, a thinly veiled account of the 1924 murder of Bobby Franks. Leopold died in 1971.

Leopold and Loeb were not the only infamous prisoners to be incarcerated at Joliet: Baby Face Nelson and serial killer John Wayne Gacy also spent time within its walls. But by 2002, the dangerous condition of the building finally led to its closure. In 2005, the empty facility was used to add authenticity to the Fox Network series Prison Break. Now a museum, the penitentiary is open for tours, allowing curious visitors to experience something of the atmosphere in which the infamous murderers Leopold and Loeb spent years of their incarceration.

Greg King is the author of many internationally published works of history, including The Last Voyage of the Andrea Doria. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, Majesty Magazine, Royalty Magazine and Royalty Digest. He lives in the Seattle area.

Penny Wilson is the author of Lusitania and The Last Voyage of the Andrea Doria with Greg King and several internationally published works of history on late Imperial Russia. Her historical work has appeared in Majesty Magazine, Atlantis Magazine, and Royalty Digest. She lives in Southern California with her husband and three Huskies.