by Michael Breen

That day the dictator conceded, June 29, 1987, is celebrated as the starting point of democracy. It was a conception, and as is the way with power relations, more forced than gentle. People power, you might say, had shafted dictatorship and impregnated the state. The delivery was eight months later, on February 25, 1988.

That was when, forty years after the founding of their nation, twenty-five since the economic revolution, and seventy days on from the election, the Korean people inaugurated the person they had, for the first time, peacefully and properly, though noisily, chosen to lead them. They listened when he stepped up to the microphone at the ceremony on Yeouido Island in Seoul and gave a speech entitled, “We Can Do It.”

It was a familiar exhortation from the Park Chung-hee era. But this time it was about democracy. And they have been doing it, since then, the Koreans. That said, Koreans don’t celebrate that moment because they see it as Roh’s. But it was and is theirs. It marked the point at which Koreans changed from a people ruled by a person to a people governed by rules, sort of. It went from the country of kings, outsider power, Rhees, Parks, and Chuns, all of whom manipulated law in the service of their own power, to a country where the law ruled. This point often gets lost. The Earth did not move. Life did not change.

More to the point, many refused to accept Roh Tae-woo as a democratic president. They looked at his gray suit and saw a green uniform. Of course, the transfer was peaceful, they’d say, it was from the top thug in the junta to his best friend. He’s a military guy. How could he be democratic? And please don’t mention Washington and Eisenhower because this is Korea. Yes, Roh later held Chun responsible for the past, but he was forced by public opinion, and went easy, letting his buddy slip into internal exile in a temple.

No, they say, the real first democratic president was the next one, Kim Young-sam, a civilian oppositionist. This claim had many advocates, most notably Kim Young-sam. The bias is understandable. The necessary weakness of democracy is that it doesn’t come with ideological commissars. The flabby rump of old thinking continues to sit heavily on the face of the electorate. It’s no wonder voters can’t see what’s changed. The inclination remains to look to the person of the president, rather than the system by which he or she is selected and then dismissed. It doesn’t help that media remains obsessed with every move a president makes.

Like America, Korea’s presidents are treated as if they are short-term monarchs. The fact remains, though, that the presidency on that cold winter day in 1988 was a very changed office. Starting with Roh, each occupant since has been required to leave after a single, five-year term. None has tried to stay. In the first twenty-five years two and a half were opposition candidates— the half being Kim Young-sam, who cunningly merged with the ruling party and won as its candidate. One was a minor player before winning his party’s candidacy, one was a single woman, and one actually had a career other than politics. This short history already allows for a claim that Korea’s is one of the most impressive democracies in Asia.

…

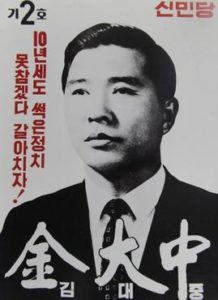

The Koreans are subject to the same intellectual temptation but refute it by example, not because they’re moral philosophers but because they know what people who seek power are up to. Kim Dae-jung, the third democratically selected president, said it best: “Culture is not necessarily our destiny. Democracy is.” This democracy is a fertile paddy, some sections of which have sprouted more thickly than others. Elections, for example, have improved each time.

The 1987 campaign was measured in outdoor rallies, many of them characterized by stone-throwing. Roh and then-oppositionist Kim Young-sam, both from the southeast, were pelted by mobs and driven from venues when they ventured to Kim Dae-jung country in the southwest; and when Kim Dae-jung went to their territory the spirit of revenge was in the air, but he knew the limits of this violence—it was not intended to really hurt anyone— and was prepared.

campaign was measured in outdoor rallies, many of them characterized by stone-throwing. Roh and then-oppositionist Kim Young-sam, both from the southeast, were pelted by mobs and driven from venues when they ventured to Kim Dae-jung country in the southwest; and when Kim Dae-jung went to their territory the spirit of revenge was in the air, but he knew the limits of this violence—it was not intended to really hurt anyone— and was prepared.

…

Consider this pattern: Each of the first five democratically elected presidents has gone through the near-exact same popularity pattern, a lurching descent after election from enormous approval ratings to an end point of political leprosy, so contagious his own party’s candidate shies away from his support. This drop in popularity poses each time as a response to failure— the arrest of aides for corruption, policies, or lack of them—but like much political conviction it is more gut than reason.

The electorate swims in a gathering current it cannot explain. People criticizing the president change tack when you come back at them. Getting to a rational explanation can be like catching the proverbial bar of soap.

Kim Dae-jung (1998–2003) had it bad. He was unfortunate in that the Dong-A Ilbo, one of the three most influential papers and previously one of his supporters, made a strategic decision to join forces with the others against him. The publisher calculated that it would be better for business. That meant, apart from one out on the left, all the main media were shooting from the same trench. I went down to Kim Dae-jung’s home island during this time and found that, even there, in the tiny community two hours by ferry off the southwest coast, they’d turned against their boy.

“We expected he’d do something for us,” the owner of an old-style tabang coffee shop moaned. A mainlander, he’d been a photographer and decided to stay after a visit years earlier.

“But he’s the president of all Koreans,” I said. “If he did something for you, that would be favoritism, maybe even corruption. In fact, don’t you admire him for not favoring you?”

“I know what you mean,” he said. And he did know what I meant. But he just felt critical. The reason, I would suggest, was that Koreans had not, on February 25, 1988, or thereafter, adjusted their view of what the presidency actually was. They knew, but didn’t really get, what had changed in terms of what a president could or could no longer do.

The ghost still occupying this space in the national psyche is our old friend Park Chung-hee, and he’s whispering: “Look at this fellow. Does he have what it takes? Has he built up an industrial base from nothing to protect us from North Korea? The whole National Assembly is yelling at him. The people are protesting against him in the street. He’s useless.”

On the face of it, any comparison with Park Chung-hee is absurd, especially considering that it takes a year to learn the job and that the last year is lame-duckery. This leaves the modern Korean leader three years to accomplish anything, not the eighteen Park had, and usually it’s against an opposition-held parliament and in the face of a highly critical media.

What’s more, how do you compete with a nation-builder when the nation is already built and able to defend itself against its enemies with or without American help? The failure to articulate the limitations of the democratic presidency falls most squarely at the feet of the presidents themselves.

MICHAEL BREEN is a writer and consultant who first went to Korea as a correspondent in 1982. He covered North and South Korea for several newspapers, including the Guardian (UK), the Times (UK), and the Washington Times. He lives in Seoul.