John T. Shaw

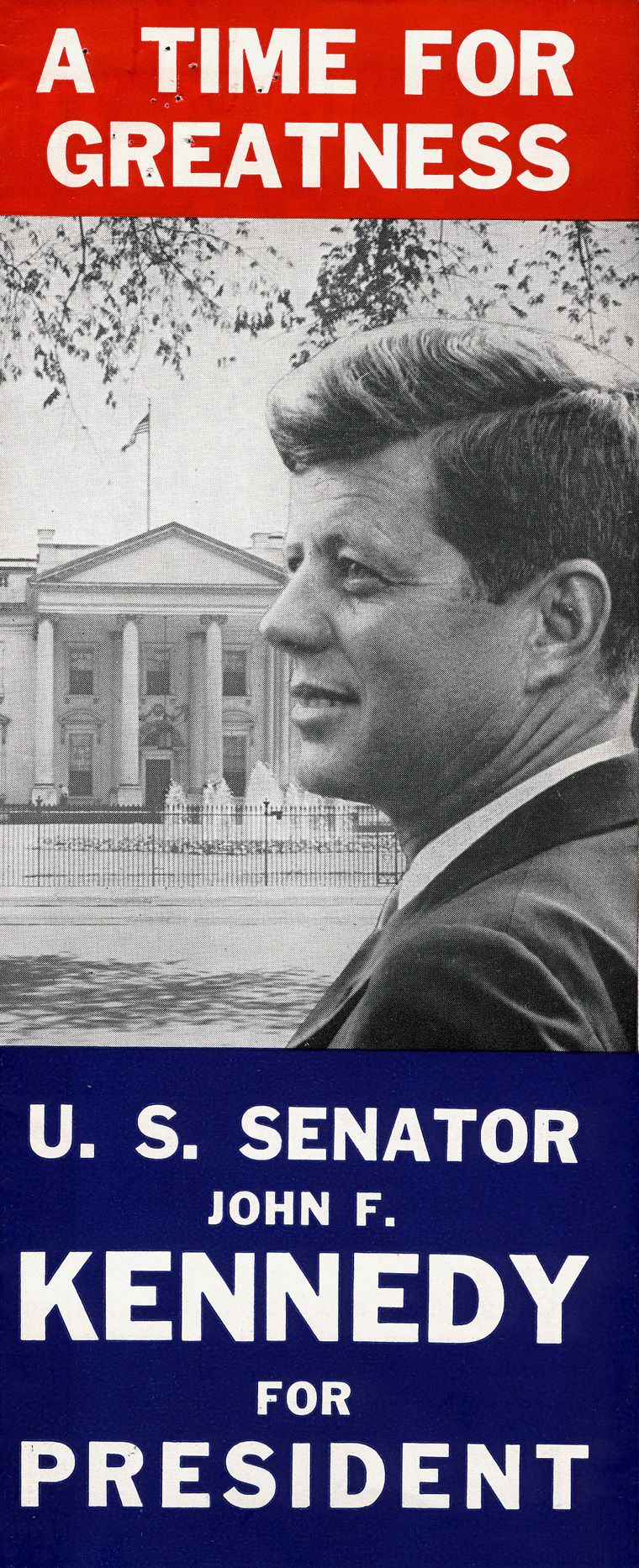

If Senator John F Kennedy in office was faced with the U.S. Senate of 2015, he would not recognize it with its frequent filibusters, fierce partisanship, and increasingly homogenous political parties in which few conservative Democrats and or liberal Republicans can be found. It is far different than the Senate in which Kennedy served from 1953 to 1960.

But he would surely recognize the political aspirations of a number of senators who may be considering a run for the presidency in 2016: Republicans Marco Rubio of Florida, Ted Cruz of Texas and Rand Paul of Kentucky and Democrats Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, Kirsten Gillibrand of New York and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. Kennedy would spot the ambition in their eyes, their impatience with the desultory pace of the upper chamber, their evident delight in lavish press attention, and their ample self-confidence that they’re as deserving to reside at the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue as the current occupant—or any of their potential rivals.

Kennedy knew the Senate had never been an advantageous place from which to win the presidency. Before his 1960 election only Warren Harding, in 1920, had gone directly from the Senate to the White House. And since JFK’s election only one sitting senator has successfully retraced his steps: Barack Obama in 2008. Even a partial list of those senators who tried and failed to win the White House is long, often illustrious, and spans the centuries: from Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John Calhoun to Robert Taft, George McGovern, and Edward Kennedy, to recent bids by John McCain, John Kerry, Joe Biden, and Hillary Clinton.

There are many theories about why it’s so difficult for a sitting senator to be elected president. Senators cast scores of votes that can be used against them on the campaign trail. They learn a professional language that, while usually understandable on Capitol Hill, is often impenetrable to the general public. The skills needed to be a good senator are different than those of a successful presidential candidate.

I believe there is a JFK model of how to use the Senate to win the presidency that Obama adopted in 2008 and which current aspirants would do well to follow. Here are some lessons JFK could offer on how to travel directly from the Senate to the White House.

1. Don’t wait for gray hair.

A peculiar, perhaps even perverse, aspect of American democracy is the endless yearning for something, or someone, new. Additionally, windows of opportunity in American politics often open slightly and briefly, and then close abruptly. The senator who decides to wait another four years before running for president can easily become an afterthought by the time the next election rolls around. During the 1960 campaign, JFK repeatedly brushed aside suggestions that he wait at least four years more years until running for president. He said he would likely get elected in 1960 or never.

2. Be single minded in pursuing the presidency; ambivalent candidates never win.

The graveyard of failed presidential campaigns is littered with the remains of senators who were conflicted as to whether their primary responsibilities should be in Washington or on the campaign trail. JFK never suffered from this dilemma. Once he decided to run, he ran hard and didn’t look back. During the 1960 campaign Kennedy faced more experienced and more highly regarded rivals: Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson, Democratic senators Hubert Humphrey and Stuart Symington, and former Democratic presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson. But while they equivocated and anguished about whether and how to run JFK pursued the nomination relentlessly for four years.

3. Use the Senate as a credential.

JFK understood that as a senator he carried considerable cachet; with creativity and tenacity a senator can gain national visibility and be seen as an important policymaker. It is still a calling card today for being taken seriously by the media and public. A seat on the Finance, Budget, or Appropriations committees gives reputation for economic expertise while membership on the Foreign Relations, Intelligence, or Armed Services committees confers foreign policy and national security gravitas. JFK pleaded with Senate Majority Leader Johnson for four years for an appointment to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee before finally getting it in 1957. He wanted the seat for both substantive, and status, reasons.

4. Use the Senate as a platform.

Kennedy used the Senate as a venue to give wide-ranging speeches and his foreign policy addresses were particularly impressive. They were well written, historically literate, informative, and forward leaning. He also took full advantage of his membership on the high-profile McClellan Committee, which investigated corruption in the labor movement in the late 1950s.

5. Use the Senate as a proving ground.

JFK knew that while a great speech can create buzz in the political world, it’s also important to actually get something done, if for no other reason than to show the media and the political establishment that you can deliver. In many ways like today’s immigration reform, Kennedy found himself confronting labor reform, which was controversial, consequential and fraught with political risks. As the chairman of a key Senate Labor Subcommittee, it fell to Kennedy to write a reform bill. He took hits from all sides: labor, business, southern Democrats, Republicans, and most of his political rivals. But he impressed his colleagues with his ability to write complex legislation, move it through the Senate, and then negotiate a compromise with the House. He then hurried on to other less controversial matters.

6. Work hard, enjoy the moment, and pray for good luck.

Kennedy focused on those variables which he could control. He traveled the country relentlessly, lobbied convention delegates, and took full advantage of his family’s wealth to wage a well-funded national campaign. He was always aware that the outcome of the race would be close, observing that in politics the “margin is awfully small” between those who win and those who lose. “Like it is in life,” he added. Yet he exulted in the challenge. Shortly after he announced his candidacy Kennedy asked, “How could it be more fascinating than to run for president under the obstacles and the hurdles that are before me?”

JFK, as a political pro, would warn today’s young senators that the road to the White House is long, exhausting, perilous, and rarely runs through the Senate. But it can be done. Senator John F. Kennedy charted his path to the presidency in 1960 and modern aspirants would be wise to study his journey and reflect on his example because it remains relevant, even in today’s very different world.

JOHN T. SHAW is a senior correspondent and vice president for Market News International and a contributing writer for the Washington Diplomat. He is a frequent guest on C-SPAN, where he discusses Congress, as well as on KPCC, an NPR affiliate in Los Angeles. He has also appeared on the “PBS News Hour.” Shaw was a Media Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University for six years, and he speaks frequently to seminars for diplomats in Washington. He lives in Washington, DC. His latest book is JFK in the Senate.