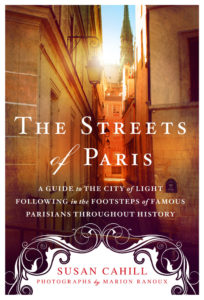

by Susan Cahill; Photographs by Marion Ranoux

The story of Henri IV in Paris is best told from high on the Pont Neuf, the New Bridge, the best-loved creation of France’s most beloved king. Henri IV (1553–1610) sits here on the bronze horse in the middle of this street over water, the longest and widest of the Parisian bridges that connect the Left and Right banks. The statue faces the elegant triangle of Place Dauphine, another jewel designed by the king who professed himself a simple cowboy: “I rule with my arse in the saddle and my gun in my fist.” Centuries after his death by assassination, the streets of Paris were still singing his praises.

Vive Henri Quatre

Vive ce roi vaillant

Vive le bon roi

Vive le vert galant!

The religious fanatics of the war-torn city hated Henri IV. The mad Catholic who stabbed Henri IV to death sixteen years after his coronation was the one assassin—out of at least twenty-three others—who tried to kill him and actually succeeded. Jesuits, Protestants (called Huguenots, Calvinists, or Reformists), and the militant Catholic League, they never stopped plotting their murderous revenge against the soldier king bon viveur who from 1589 (when Henri III died, making Henri IV next in line to the throne) to 1593 had led his Protestant troops against the rebel Catholics of Paris. Bombarding the city from the heights of Montmartre and the bell tower of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, he had hoped to force and finally starve it into submission to a Protestant king.

But then Henri IV renounced his heretic past in the abbey of Saint-Denis in 1593 and six months later was crowned king in Chartres Cathedral. After thirty years of civil war between Catholics and Huguenots, followed by Henri’s four year Siege of Paris, ordinary Parisians didn’t care, at this point, whether Henri IV’s conversion was pure or cynical. What mattered was that his submission to Rome meant no more war. According to Desmond Seward’s The First Bourbon: Henri IV of France and Navarre, there is no evidence that he ever said, “Paris vaut bien une emesse.” (Paris is worth a Mass.)

He had once written to a friend, “Those who genuinely follow their conscience are of my religion—as for me, I belong to the faith of everyone who is brave and true.” The Catholic League, in thrall to a dogmatic hierarchical authority, sneered at this shameful twist, the new heretical standard of individual conscience. So Protestant! So moderne! But ordinary city dwellers—merchants, craftsmen, bankers, artists, masons, burghers, the poor—they were all sick of hunger, sick of the ruins which papists and Huguenots and Henri IV himself had made of their city. The streets ran with feces—animal and human—the mud thick with blood and rotting body parts. The economy of France was another ruin.

Henri IV made sure not to burden the workers with the costs of his extensive building and reconstruction projects. To pay for the Pont Neuf, for instance, he taxed every cask of wine that came into the city. Enthroned in the Louvre Palace, issuing pardons to all combatants, making his visionary plans for the restoration of the broken city, he won the people’s allegiance. “We must be brought to agreement by reason and kindness,” he wrote, “and not by strictness and cruelty which serve only to arouse men.” In this magnanimous spirit, he drafted and signed the Edict of Nantes, granting tolerance and freedom of worship to the reformist religion in 1598 (the same year he undertook the Pont Neuf, origin ally planned by the Valois king Henri III). Such was his popularity that even the most rigid Catholics chose not to make war against Henri’s mandated tolerance.

ally planned by the Valois king Henri III). Such was his popularity that even the most rigid Catholics chose not to make war against Henri’s mandated tolerance.

Born into the House of Bourbon and raised in the southwest, in the kingdom of Navarre, at the time a small independent realm in the Basque country between France and Spain, he had the Gascon temperament described by Balzac as “bold, brave, adventurous, prone to exaggerate the good and belittle the bad,… laughing at vice when it serves as a stepping stone.” At every stage, Henri IV was a charmer, “his eyes full of sweetness,… his whole mien animated with an uncommon vivacity,” to quote one magistrate. The northern, more cerebral French regarded the men of the South, who spoke Provençal, as foreigners.

Henri IV was baptized in the Catholic Church but was given a Protestant tutor after his parents converted to Protestantism. When his father—but not his mother—returned to the Church, he gave his son a Catholic tutor. The boy, however, kept his mother’s reformed faith, even while studying in Catholic Paris at the College of Navarre on the hill of Sainte Geneviève.

The Wars of Religion raged during his adolescence when he left the College of Navarre and returned to his family’s kingdom. Henri IV saw for himself the torture and barbarism each of the warring sects inflicted on the other. In 1572, he once again left home to travel north to Paris where his arranged marriage with the Catholic Marguerite de Valois (Margot), sister of the Valois king Charles IX and daughter of the royal poisoner Queen Mother Catherine de Medici, was seen at first as an occasion of joy, a sign that the Papists and the Huguenots would now stop killing each other. (For Marguerite’s bridal emotions, see “La Reine Margot: Legends and Lies,” p. 229.)

Thousands of Protestant nobles came to Paris to enjoy the party. They were invited to occupy rooms in the Louvre. (Some stayed home in their châteaux, possessed of a strange sense of foreboding.) The marriage festivities, despite the bride and groom’s distaste for each other, obvious during the ceremony outside the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, lasted almost a week. Then, to the signal of triumphant Christian church bells, horror exploded. What became known as the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, of Protestants by Catholics—raged throughout the next three nights and days.

The Protestant bridegroom, expecting death, hid in the Louvre and later, under “house arrest” in the corridors of the Château de Vincennes, at that time a state prison.

Plotting but failing to escape from Paris over the next four years, Henri IV played the game of pretending to enjoy the pleasures of the city, hunting in the royal forests landscaped under François I (Bois de Boulogne and Fontainebleau) as well as gambling, tennis, women, strolling through the gardens of the Louvre. The new bride tried to help her husband escape. Alexandre Dumas’s novel La Reine Margot portrays her as Henri’s loyal protector.

Finally he got away, home to Navarre, hoping never to set eyes on Paris again. Following the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, there were eight more civil wars involving Catholics and Protestants. Henri saddled up to join the nonstop bloodletting over whose religion was the True one, the surest ticket to paradise. No wonder Henri IV came to detest the absurdities of partisan religion, wanting no part of it once he was king. The slaughter ended only on the day he genuflected to Rome in Saint-Denis. War had not worked; conversion, he realized, was the only way to win over Catholic Paris and be crowned Rex Christianissimus, Most Christian King. (Montaigne believed that though a firm Calvinist under his mother’s influence, Henri’s warm earthy personality was more suited to the Catholic faith than to the icy purity of Protestantism.)

What was not understood about Henri IV in 1594 when as king he settled into the Louvre palace and took jubilant carriage rides onto the Île de la Cité to hear High Mass at Notre Dame was his love of beauty. He was determined to transform the filthy ruins of Paris into a place fit for civilized human beings: “To make this city beautiful, tranquil, to make [it] a whole world and a wonder of the world.” A visionary and a pragmatist, by the time he was murdered, Henri IV had made the medieval city of Paris into a modern capital: “the Capital of the World” as it came to be called, for centuries.

SUSAN CAHILL has published several travel books on France, Italy, and Ireland, including Hidden Gardens of Paris and The Streets of Paris. She is the editor of the bestselling Women and Fiction series and author of the novel Earth Angels. She spends a few months in Paris every year.

MARION RANOUX, a native Parisienne, is an experienced freelance photographer and translator into French of Czech literature.