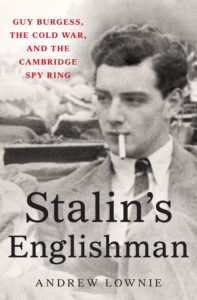

by Andrew Lownie

When Harold Macmillan, now the Prime Minister, visited the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in February 1959, Guy Burgess told Harold Nicolson that he was ‘able to give advice at a suitable level’ and remembered how he had once spent an evening with him at the Reform, where Macmillan ‘had listened – as who could not as it was my club – to my rantings’. And to Stephen Spender, he confided, ‘I was able to be a good deal of help to Macmillan during his visit. I wrote a report that he was in favor of friendship and should be trusted, whereas all the others wrote that he was a dangerous reactionary.’

Guy Burgess used the opportunity of the visit to reiterate his desire for safe passage to see his sick mother, enlisting a host of former contacts to make his case, including Sir Patrick Dean, now Deputy Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office, who had accompanied Macmillan, telling him, ‘I will not make embarrassments for Her Majesty’s Government if they don’t make them for me. I will give no interviews without permission. I was grateful in the early days that Her Majesty’s Government said nothing hostile to me and I, for my part, have never said a lot of things that I could have said.’11 The implicit threat was there.

The Randolph Churchill Call

He also rang Randolph Churchill, who was on the delegation as a journalist, and asked to see him. Randolph Churchill later wrote that Guy Burgess appeared in his room in Moscow’s National Hotel, introducing himself, ‘I am still a communist and a homosexual.’ To which Randolph replied, ‘So I had always supposed.’

Read more about how thousands of men are to be pardoned by the UK here

The government now began to look seriously at whether anything could be done if Burgess, whose passport had expired in 1958, chose to travel to Britain.The Attorney General Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller, reviewing the evidence against Burgess, concluded there was not enough evidence to prosecute him for spying under section one of the Official Secrets Act and only technical offences under section two had been committed. On 17 February the Cabinet discussed Burgess and thought it might ‘be advisable to require him, if he presented himself at a British port, to establish his identity and to prove that he had not become an alien by acquiring Soviet nationality’.

A Treasonable Act while in the Soviet Union?

David Ormsby-Gore, who now had Hector McNeil’s job as Minister of State at the Foreign Office, reported to the Cabinet on 25 February, ‘We cannot hope to obtain legal proof that Burgess has committed any treasonable act while in the Soviet Union or any seditious act . . . Indeed if he knew how little evidence we had, he would be more likely to be encouraged than deterred.’

The following day the Foreign Office informed the Moscow embassy they were not to extend any travel facilities to Guy Burgess and hoped he didn’t put the issue to the test. ‘The Cabinet considered the question of Burgess this morning. They were advised by the Attorney General that there are no (repeat no) grounds on which Burgess could be prosecuted by the Crown if he returns to this country. Nor are there any means of preventing him from returning if he is determined to do so.’

Guy Burgess seemed to be aware of the weakness of the case against him, writing to Harold Nicolson:

I won’t go into long details about the so-called ‘evidence’ of which you write except to say (what I know is the case) that so nervous are the authorities of what might happen if I come back that they drop deep hints to selected persons known to be in touch with me that there is evidence for a case. In private, I know that the authorities say to each other (as a senior British ambassador said to a friend of mine, not knowing he was a friend), ‘The trouble is we don’t know what we could do if he came back. There is no evidence.

A Pragmatic Guy Burgess

But Burgess was pragmatic. ‘I am bound to take into account that a case might be drawn up by the authorities I mention and to fight it would incur publicity and calling as witnesses all sorts of good friends to whom I have done enough harm already.’

It remained a lonely life, only enlivened by ‘chance’ meetings with foreign visitors. Patrick Reilly, who served in the embassy until August 1960, recalled, ‘Once he accosted a newly arrived American admiral, who was wearing a brand new Old Etonian tie, saying how interested he was to see that they had been at the same school.The admiral, much embarrassed, explained that he had just bought the tie in the Burlington Arcade, because he thought it pretty.’

Revealingly, when Paul Robeson, a former lover of Coral Browne and hero of Burgess, was taken ill in Moscow in the spring of 1959 and had to spend a month at a sanatorium, Burgess confessed to Browne he was ‘too shy to call on him . . . I always am with great men and artists. Not so much shy as frightened . . . tho’ I know that he is as nice as can be . . .’

Mischief with Journalists

Guy Burgess was now in regular touch with various journalists and enjoying the mischief he could make. Robert Elphick, Reuters correspondent in Moscow from 1958-62, remembered ‘Burgess at various parties in a grey suit, rather stained and baggy, and wearing an Old Etonian tie. He had usually had too much to drink but was lucid.’ Elphick once asked him if it had all been worth it. ‘“Well, we all make mistakes,” he replied.’ The Observer journalist, Edward Crankshaw, saw Burgess several times on a visit in January 1959. He reported to the Foreign Office:

I had better say at once that I had not been with him long before I understood what I had failed to see before. B’s brilliance and charm. . . I have never known anyone who flaunted his homosexuality so openly: whether he did this in England others will know. But he neither bullied one nor bored one with it. And once I got accustomed to this stage atmosphere I liked him much and finished up by being deeply sorry for him, although at no time did he exhibit self-pity or ask for sympathy. Only for the opportunity to talk and talk and talk . . .

ANDREW LOWNIE first became interested in the Cambridge Spy Ring when, as President of the Cambridge Union Society in 1984, he arranged an international seminar on the subject. After graduating from Cambridge University, where he won the Dunster Prize for History, Lownie went on to take a postgraduate degree in history at Edinburgh University. He is now a successful literary agent, and has written or edited several books, including a biography of John Buchan.