by Lorissa Rinehart

The French had dropped a veritable drag net across the country to keep the world from learning about the Algerian War of Independence. The colonial government censored airwaves and telegraph wires for any information about the conflict. Razor wire lined hundreds of miles along Algeria’s border. The last Western reporter who actually got into Algeria had been caught, imprisoned, and sentenced to death. The Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) broke him out, but there were no guarantees they would be able to do the same for her.

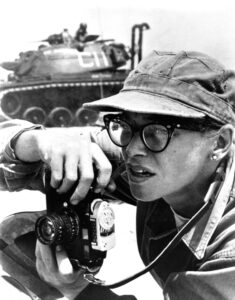

Having just been released from a communist jail in Budapest, Dickey Chapelle well knew the risks and the reality of imprisonment under tyranny. But Dickey pressed forward nevertheless, faked her own kidnapping then wound her way through Algerian underground to reach the foothills of the Atlas Mountains where the FLN were making their stand. She spent 17 days in the field with the Scorpion Battalion, the FLN’s closest approximation to special forces. She went on patrol with them, hid from enemy planes, and sipped Turkish coffee around the campfire while trading war stories. She learned how to march ten miles in the desert on a handful of dates and two cups of water. She rode out on horseback to photograph a Bedouin village decimated by U.S. made bombs dropped by French pilots. She crawled into the dark of a camel hair tent to interview a man who had been machine-gunned by French soldiers after being made to walk over a stretch of road they suspected of being mined. And she covered the trial, conviction, and execution of a teenage collaborator who had aided the French in killing dozens if not hundreds of civilians.

But now, she had to get out of Algeria, an endeavor no less dangerous than getting in. As a White, blond, American woman, she would be immediately recognizable if seen in public and the French offered cash rewards to Algerians who reported anything out of the ordinary.

She left the Scorpion Battalion at sunrise and she entered a high-walled compound on the Algerian frontier as the sun slid below the horizon. Having stopped there while traveling the other direction, she noted the stack of crates containing C4 had been diminished slightly. Her guide, who only ever identified himself as Ali, took her to the women’s quarters. They welcomed her in and ushered her to a sleeping pallet in the corner.

The next morning they fed her pancakes and told her to take off her clothes. She was still wearing the fatigues she had been issued while covering the Marines as they made their final push on Iwo Jima and beat back WWII’s last tide of fascism. In place of stiff twill, they wrapped her in soft blue cotton tied at the waist and draped over her head. Fatima, Ali’s daughter, placed a veil across the bridge of her nose, tied its two ribbons, then stepped back and nodded in approval. But Dickey was not so sure.

Outside, Ali handed her a crude package tied in burlap that looked like the burden of so many Arab women coming back from the market. But in truth, it contained her typewriter, notes, and 150 negatives documenting the war that the French did not want the world to see.

The bus she hoped to be her escape kicked up a cloud of dust in the distance.

“Ali will be your husband on the bus,” Fatima told her. “You will hear no other voice but his, no matter what is said. And you will not raise your eyes but to his.” Then she added as if a second thought, “Of course, if you survive him, you are permitted to identify yourself. But not until you have been attacked and captured.”

The bus rolled to a stop. Dickey cast her eyes down and kept them there for the next twelve hours as she rode in silence out of French-occupied territory and back to safety, back to freedom.

She could not eat or drink or sleep, terrified any would give her away. Nor could she look out the window, instead keeping her gaze fixed on the countersunk Phillips screw holding the seat in front of her fixed and her thoughts focused on all she had seen.

It had not been what she had expected, nor what she had prepared herself for. The newspapers back home reported the conflict in Algeria as a minor scrum, domestic and contained. But she had witnessed an all-out shooting war, marched with an army as organized and well-trained as any other, and met a people united in their desire for nationhood. She could hardly believe the French who had themselves fought the tyranny of fascism in WWII would oppose the Algerian struggle that she would later identify as Jeffersonian in its aim of self-determination. It pained her even more that America whose ideals she loved like they were her children would aid and abet this unjust war. As one Scorpion Battalion soldier told her, “You know, your country is really my country’s chief enemy. Not France, for we can bleed France white. But always America revives her with arms and money when she would faint without them.”

It was a hard lesson, but one Dickey learned well, that even in the so-called Free World people still struggled to be free, often and even against the United States of America. From then on, her loyalties as a reporter and a human being lay not within the borders of a nation, but with those who fought for freedom on the front lines of the Cold War.

Cultural critic and historian Lorissa Rinehart writes about art, war, politics, and the places where these discourses intersect. Her writing has recently appeared in Hyperallergic, Perfect Strangers, and Narratively, among other publications. She holds an MA from NYU in Experimental Humanities and a BA in Literature from UC Santa Cruz.