by Siân Evans

As a new war erupts in Europe, Siân Evans recounts the tale of a heroic British nurse working behind enemy lines in Belgium during the First World War. Edith Cavell’s court-martial and execution by firing squad was to have international repercussions, but it is her humanity that has such lasting resonance today.

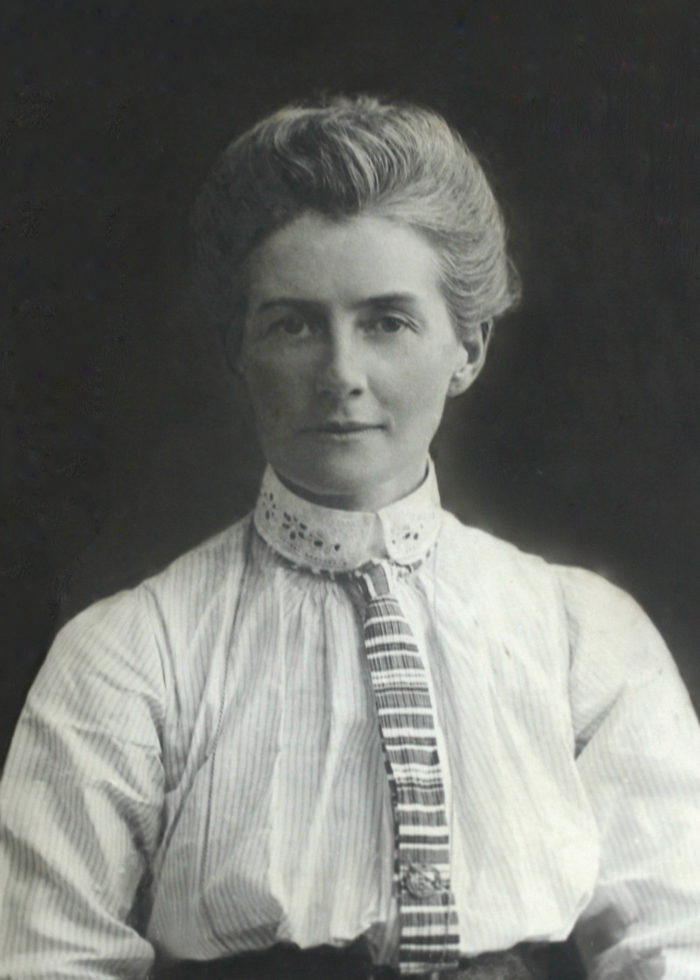

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Edith Cavell was born in 1865, the eldest daughter of a cash-strapped Norfolk clergyman, and she had an idyllic rural childhood. Edith had a passion for drawing and painting, and a gift for the French language. She worked as a governess for a family living in Belgium but discovered a vocation for nursing when her father fell ill and she returned to England to take care of him. She was subsequently trained as a nurse by Matron Eva Luckes, a pupil of Florence Nightingale, and she gained experience and accolades in a number of English hospitals. In 1907, Edith was appointed the Matron of the first nursing school in Belgium, L’École Belge d’Infirmières Diplômées.

In Europe in the early twentieth century, nursing was largely considered to be the sole domain of working women. In Belgium, only nuns were allowed to work in infirmaries. Career opportunities for well-educated women outside the home were severely limited, but Edith was a pioneer, leading by example, successfully training scores of younger women of all classes and many nationalities to become competent and dedicated nurses.

In August 1914, Edith was visiting her recently widowed mother in Norfolk when the Great War broke out. She immediately returned to Brussels, saying: “At times like this, they need me more than ever.” Belgium was rapidly overrun by German forces, and the nurses’ training college was closed, but Edith transferred to the Berkendael Medical Institute in Brussels, now administered by the Red Cross, to supervise the nursing of casualties. She instructed her staff to treat the wounded of all armies, as well as the civilian population, to the best of their abilities, without discrimination.

Edith had already been a contributor to Nursing Mirror for eight years, and she became their official war correspondent, providing vivid accounts of hospital life during wartime. She related the grueling nature of life under foreign occupation, the hazards of working near a battlefield, the harrowing ordeal of ministering to badly wounded men, the constant shortages of medicines and materials, and the physical and psychological traumas suffered by dispossessed refugees and non-combatants. In her hard-hitting eyewitness accounts, Edith was one of the first women to report from an active war zone, a place of considerable danger. Her words from August 21, 1914, have an awful, recognizable immediacy:

“There were at least 20,000 soldiers who entered the city…our chief thought was how to care for those who were sacrificing so much, and facing death…homes have been burnt and battered, villages razed to the ground, women and children murdered, drunken soldiers raping, looting and mutilation…we have been cut off from the world.”

Edith’s own loyalties were tested one night when two English soldiers begged for her help in avoiding arrest. She hid them on site for two weeks, then had them taken secretly to Holland and freedom so that they could rejoin their regiments, rather than languishing in a prisoner of war camp. Within months Edith had masterminded the clandestine escapes of more than 200 British, French and Belgian soldiers.

The penalties for helping the enemy were severe, and before long German suspicions fell on Edith. On August 5, 1915, she was arrested with 34 others and accused of treason. Scrupulously honest, she readily admitted her part in helping Allied soldiers escape. Edith’s accusers drew up a confession in German, a language she did not speak, and she faced a court-martial on October 7. Her courtroom trial lasted three minutes and she was not allowed a defense attorney. Found guilty, she was sentenced to death by execution.

There were international appeals for mercy for this 49-year old devoted nurse, who had treated all her patients with sympathy and compassion, regardless of their nationalities. Edith faced her imminent death with equanimity. The night before she died, she told the Anglican cleric praying with her:

“Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.”

She was executed at dawn on October 12, 1915, by a German firing squad of 8 soldiers. When her body was examined after her death, only 4 bullet wounds were found—half of the execution squad had deliberately shot wide of their target rather than be a party to her death.

The news of Edith’s death spread worldwide and caused outrage across Allied and neutral countries alike. In Britain, during the 8 weeks after her death, recruitment to the armed services doubled, as so many men volunteered to join up in her memory.

After the war, in 1919, Edith’s body was exhumed from its shallow grave and conveyed back to Britain. 250,000 people lined the streets of London, and a memorial service was held at Westminster Abbey; newsreel footage of the day shows her flower-bedecked coffin on the shoulders of pallbearers, some of whom were former soldiers whom Edith had helped to escape.

Edith’s body was then taken back to her beloved Norfolk. Crowds lined the route of the train bearing her coffin and she was buried in Norwich Cathedral. On March 17, 1920, an imposing monument to her memory was erected in St. Martin’s Place, just off Trafalgar Square in London. The granite pylon is 45 feet high, and each of its four sides of the column bears a single word; Fortitude, Devotion, Sacrifice, and, finally, Humanity. Immortalized in Carrara marble, today the statue of Edith in her nurse’s uniform meets our eyes with dignity and grace, a martyr to her principles of compassion.

Siân Evans is the author of Maiden Voyages: Magnificent Ocean Liners and the Women who Traveled and Worked Aboard Them, published by St Martin’s Press.