by Bob Drury & Tom Clavin

Daniel Boone was too far away to hear his oldest boy’s screams as the tall Indian tore out the sixteen-year-old’s fingernails one by one.

James Boone was already bleeding out from a gunshot wound. Now, prostrate on the frozen scree beneath the Cumberland Mountain’s shadow line, he begged the Shawnee with the high cheekbones and misshapen chin to just kill him. His persecutor was not moved. Young Boone knew the sullen warrior understood English. His family had often welcomed the Indian, known as Big Jim, into their hearth.

The raiders had sprung the ambush just before daybreak. While James Boone and his seven companions slept beneath rough woolen blankets and buffalo robes, a mixed band of painted Delaware, Cherokee, and Shawnee crept into their camp. It was not much of a fight. The two Mendinall brothers were killed instantly, their scalps lifted with trilling shrieks. Only the evening before, the others had laughed when the young farm boys had been frightened by the howls of a wolf pack.

At the first rifle report the woodsman Crabtree, a veteran Indian fighter, sprang from his bedding and plunged into the thick spinneys of chestnut, oak, and ash on either side of the mountain trail. His rapid reaction saved his life. And one of the two slaves escaped by burrowing unnoticed into a nearby pile of fallen timber. The other, an older black man, was not as spry; his life would end with a tomahawk cleaving his skull.

The youngster named Drake, whom James Boone had only just met, took a ball to his chest yet still found the strength to lurch into the woods; his remains would be discovered months later wedged between two ledges of rock face less than a mile from the scene.

Both James Boone and the seventeen-year-old Henry Russell had been gutshot, the lead balls lodging in their hips. Incapacitated, fair game.

Several of Russell’s fingers were sliced away fending off the scalping knife. His throat was finally slit and his head stove in with a war club. James Boone cried out for the same. He was eventually accommodated, but not before his toenails were also ripped away.

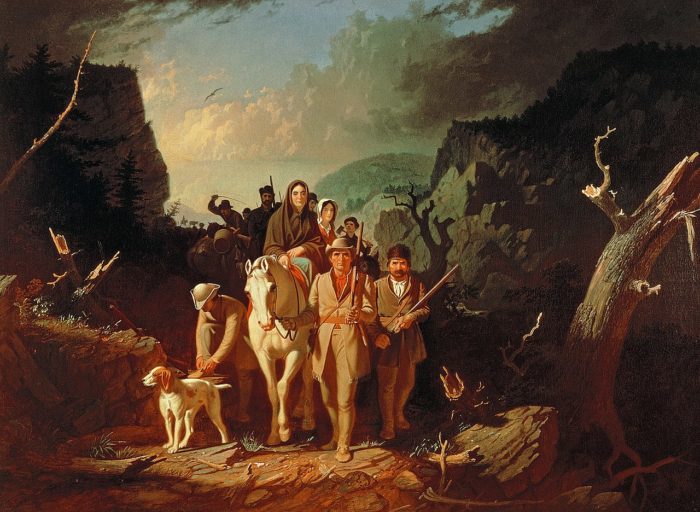

It was October 10, 1773, and several miles up the road Daniel Boone was growing impatient. His son James’ party should have returned by now. The stolid frontiersman was preparing to pilot the first company of settlers through the Cumberland Gap and into the trackless territory of Kentucky. He was eager to be off.

Boone’s company of a half dozen families had made camp the previous morning a mere one hundred miles east of the renowned notch in the Cumberland range. There they had been joined by a troop of several dozen mounted men from Boone’s North Carolina community, who had traversed the Blue Ridge by a different route. The plan was for the lone riders to travel with Boone’s packhorse caravan into Kentucky, establish farmsteads and plant spring crops, and return to retrieve their wives and children the following summer. A number of Virginia men who had attached themselves to the rough trekkers expected to do the same.

All that remained to set the expedition in motion was his son’s return with the additional stores supplied by the enterprise’s nominal boss, the Virginia militia leader, Captain William Russell. It was to Capt. Russell whom Boone had dispatched James and the teenage John and Richard Mendinall the previous day. James was to inform Russell that he should bring along extra horses and livestock.

It was late afternoon when James Boone had found Russell not far from his homestead on the Clinch River. The captain informed him that he would see what he could do about rounding up more cattle and horses before he and his small troop set out at sunrise the next day. In the meanwhile, Capt. Russell and his son Henry laded an array of packhorses with scythes and hoes, sacks of flour and seed corn, and bags of salt. At the last moment the elder Russell wrapped a parcel of books in oilskin and jammed them into a crook of his son’s saddlebag. Among the tomes was his family Bible. He then instructed Henry, the youth named Drake, and the two black slaves to accompany the Mendinalls and James Boone back to his father’s campsite. The local long hunter Isaac Crabtree volunteered to help them manage the small drove of cattle trailing behind.

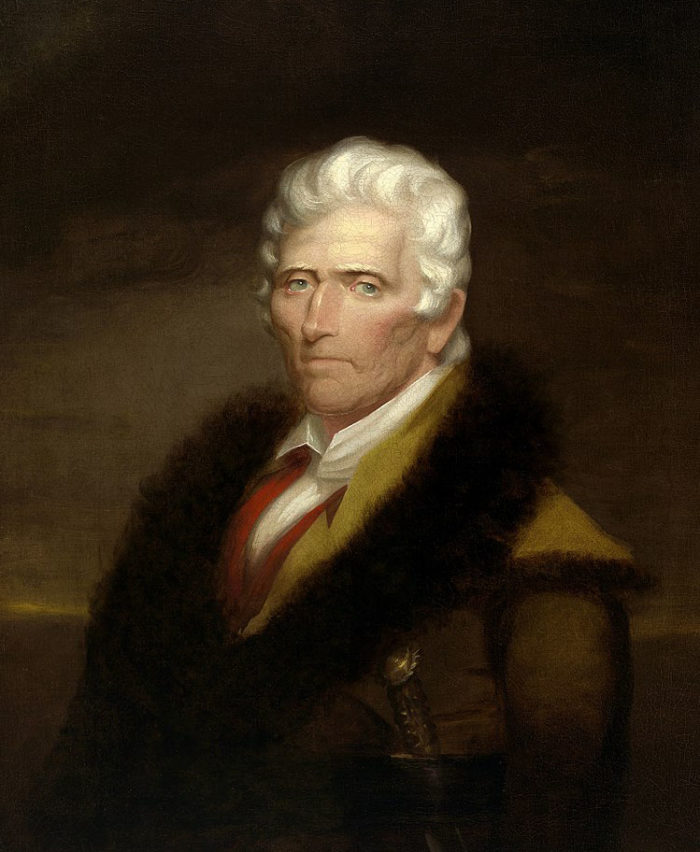

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

From nearly the first moment European emigrants set foot on the New World’s fatal shores, white men and red men had engaged in constant, bloody, and usually one-sided combat. This was not by accident. In 1607 the London directors of the Virginia Company that established the Jamestown Company had for good reason named the soldier of fortune John Smith as one of the expedition’s leaders. Similarly, when English pilgrims dropped anchor near Plymouth Rock thirteen years later, they looked to an experienced military officer named Miles Standish for direction.

The wars of conquest that followed had combined with starvation, disease, and societal collapse to result in the extinction of almost 90 percent of North America’s pre-Columbian population—an estimated nine million indigenous peoples perished. By the time Daniel Boone and his migrating pioneers were preparing for their journey into Kentucky, Native American tribes from the Canadian border to the Piney Woods of Georgia were being swept from their ancestral lands by the onrushing tide of intruders from across the sea.

In effect, it was a slow-motion genocide for the Hurons and Iroquois in the North; for the Delaware, Shawnee, Wyandot, and Mingoes of the mid-Atlantic; for the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, and Choctaw in the South. In the Floridas the Seminoles were being hunted to extermination by the Spanish, whose Conquistadors had taken to unleashing bloodhounds to track them, and vicious Irish wolfhounds to tear them apart. And even the more northwesterly peoples, such as the Ottawas, Chippewa, Miami, Kickapoo, and Sauk and Fox were experiencing the ripple effects of the white infestation in the forms of European germ-ridden foreign goods traveling ancient trade routes. The violent treatment of North America’s Eastern Woodlands tribes forecast the blood trails that would crisscross the prairies of the American West a century later.

For the first European Americans spilling over the Appalachians, the very notion of the ever-shifting and expansive frontier was a “galvanizing vision,” as one borderlands observer noted, “a space for reinvention unburdened by society, history, and one’s own past.” The “tawny serpents” of color who stood in their way were viewed, as the noted American historian Frederick Jackson Turner had it, as no more than a brutish people temporarily impeding “the procession of civilization.”

Conversely, to the continent’s indigenous tribes, Turner’s “meeting point between savagery and civilization” represented less an intersection of cultures than a deliberate and violent collision. A succession of Cherokee wars had failed to stem the tide, and Pontiac’s subsequent rebellion had similarly ended in Native American ignominy.

Yet for a tranche of tribal warriors now facing an overwhelming second wave of agents of empire traversing the eastern mountains in the guise of traders, mapmakers, and surveyors with their ubiquitous “rod and chain,” it was again time to make a stand. Particularly aggressive nations, such as the Shawnee, stoked the resentful embers among the disparate indigenous peoples up and down North America’s eastern timberland.

On that brisk autumn morning of October 1773, the slaying of Daniel Boone’s teenage son James and his company so close to the Cumberland Gap was merely the latest casualty in that existential clash.

It was on toward noon when Capt. Russell came upon the mutilated bodies splayed across the trail. The horses, cattle, flour, and salt were gone. The Russell family Bible was still packed tight in his son Henry’s saddlebags. Henry’s corpse, nearly unrecognizable beneath great splotches of brown dried blood, had been pocked by a cluster of birchwood arrows, as had James Boone’s mangled remains. Their fletchings riffled in the morning breeze.

Russell and his men unpacked shovels and handpicks. They were still breaking the near-frozen ground when Daniel Boone’s younger brother Squire Boone arrived with a party of riflemen. Up the road a camp straggler had already sounded the alarm about Indians prowling the trail, and Daniel had instructed Squire to carry with him several woolen burial sheathes sewn by James’s mother, Rebecca. Shrouds for a journey farther than Kentucky. The bodies were wrapped in the coverings before being lowered into the ground.

The assailants had positioned painted hatchets and death mauls in a circle around the slain. It was a well-known show of bravado—and a declaration of war. Squire Boone told Capt. Russell that his brother Daniel was already hewing saplings and shrubs to throw up a defensive barricade. No one could tell precisely how many Indians had taken part in the massacre, nor if they would now set their sights on the larger company of whites up the trail. Their sign indicated they were headed north. But it was not unusual for war parties to feign retreat and circle back. There was nothing to do but prime flintlocks and wait.

Copyright © 2021 by Bob Drury & Tom Clavin.

Bob Drury and Tom Clavin are the #1 New York Times bestselling authors of The Heart of Everything That Is, Lucky 666, Halsey’s Typhoon, Last Men Out, and The Last Stand of Fox Company, which won the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation’s General Wallace M. Greene Jr. Award. They live in Manasquan, New Jersey, and Sag Harbor, New York, respectively.