By Callie Oettinger

Dodger President and general manager Branch Rickey needed:

A man of principle. A moral man… I had to get a man who could carry the burden on the field. I needed a man to carry the badge of martyrdom.

Jackie Robinson was that man.

From the New York Daily News article “Jackie’s words echo thru the years“:

Rickey knew of Robinson’s performance at the court-martial, which confirmed he was the towering opposite of low and uncouth.

What Court Martial?

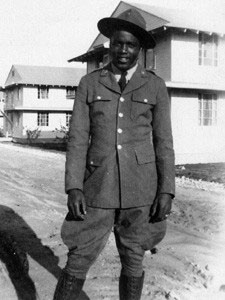

Before Jack “Jackie” R. Robinson broke records and barriers in baseball, he was in the U.S. Army—a second lieutenant assigned to the 761st Tank Battalion, the “Black Panthers.”

July 6, 1944, as Robinson road from Camp Hood to the base hospital, the bus driver ordered him to move to the back of the bus.

He refused.

From I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography of Jackie Robinson:

I was aware of the fact that recently Joe Louis and Ray Robinson had refused to move to the backs of buses in the South. The resulting publicity had caused the Army to put out regulations barring racial discrimination on any vehicle operating on an Army post. Knowing about these regulations, I had no intention of being intimidated into moving to the back of the bus. . . .

When we reached the last stop on the post . . . the driver jumped out of the bus . . . returning quickly with his dispatcher and some other drivers. . . . We heard the screeching of tires and a military police jeep pulled up. The two military policemen asked a few questions, then, with great politeness, asked if I would be willing to go along with them to talk to their captain.

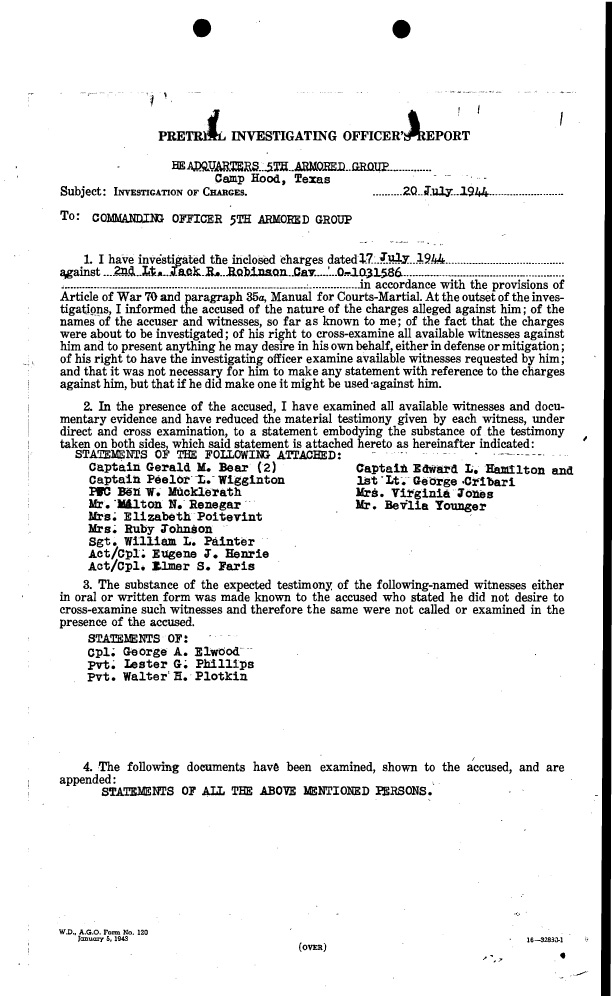

In his official Statement (see Pretrial Investigating Officer’s report below), Captain Peelor L. Wiggington stated:

When I entered the Guard Room Lt. Robinson was talking in an insolent manner and directing his words to the Sergeant of the Guard, and a Pfc. Ben W. Mucklerath. I inquired of Sgt. Painter as to the nature of the trouble , and he informed me that Lt. Robinson had been picked up at the Central Bus Station upon the request of the dispatcher there, for creating a disturbance. I then asked the Lt. to give me a resume of the incident, and he gave me the following story: that he had boarded a Camp shuttle bus outside the colored officer’s club, and saw a colored girl, a Mrs. Jones, wife of an officer on this Post, sitting about half-way down the aisle of the bus; he sat down with her and before arriving at the next Bus Stop the bus driver told the Lt. that if he did not move he would make plenty of trouble for him when they arrived at the Central Bus Station. When they arrived at the Bus station the driver asked the Dipatcher to call the MP’s and Lt. Robinson told me that he then told the bus driver that “If you don’t quit fuckin’ with me I’ll cause you plenty of trouble.” He said that the white soldier, Pfc Mucklerath, and some others were standing there and that they called him a nigger, and that some white lady said she was going to report him to the MP’s and that he told them he didn’t care what they did, that he didn’t know what a “nigger” meant, and that anyone who called him that was going to get into plenty of trouble.

I then asked Pfc. Mucklerath for his statement regarding the incident, and he gave me the following story: That he was standing outside the Bus Station waiting for a bus when the bus on which the colored Lt. was riding pulled into the Station, and that there was quite a lot of loud and vulgar talk going on. That he saw the colored Lt., Lt. Robinson get off the bus and was following a white lady toward the Bus Station, and that he heard the colored Lt. say to the lady: “I don’t care if you do report me, and if you don’t quit fuckin’ with me you’ll get into trouccble.” At this point in Pfc. Mucklerath’s story, Lt. Robinson interrupted and said that he was not addressing the white lady, but was addressing Pvt. Mucklerath because he had heard Mucklerath say something about a nigger. . . . While he was talking to me and while I was talking to him, Lt. Robinson was leaning on the high desk in the interior Sgt of the Guard Room, in a very disrespectful manner. His attitude in general was very insolent, disrespectful, and smart-alec, and certainly his actions were unbecoming to an officer and a gentleman, particularly in the presence of the enlisted men together with other officers.

In the official Statement (see Pretrial Investigating Officer’s report below) from Mrs. Virginia Jones, the woman Robinson sat next to on the bus:

I got on the bus first and sat down, and Lt. Robinson got on and came and sat beside me. I sat in the fourth seat from the rear of the bus, which I have always considered the rear of the bus. The bus driver looked back at us, and then asked Lt. Robinson to move. Lt. Robinson told the bus driver to go on and drive the bus. The bus driver stopped the bus, came back and balled his fist and said, “Will you move to the back?” Lt. Robinson said, “I’m not moving,” so the bus driver stood there and glared a minute and said, “Well just sit there until we get down to the bus station.”

From Justice Paul E. Pfeifer, in his article “The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson“:

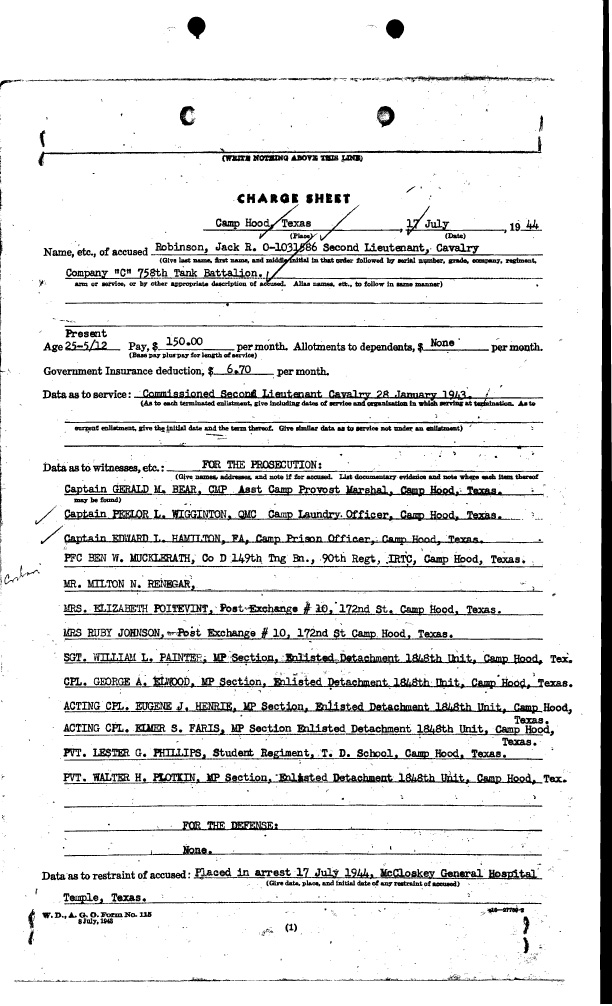

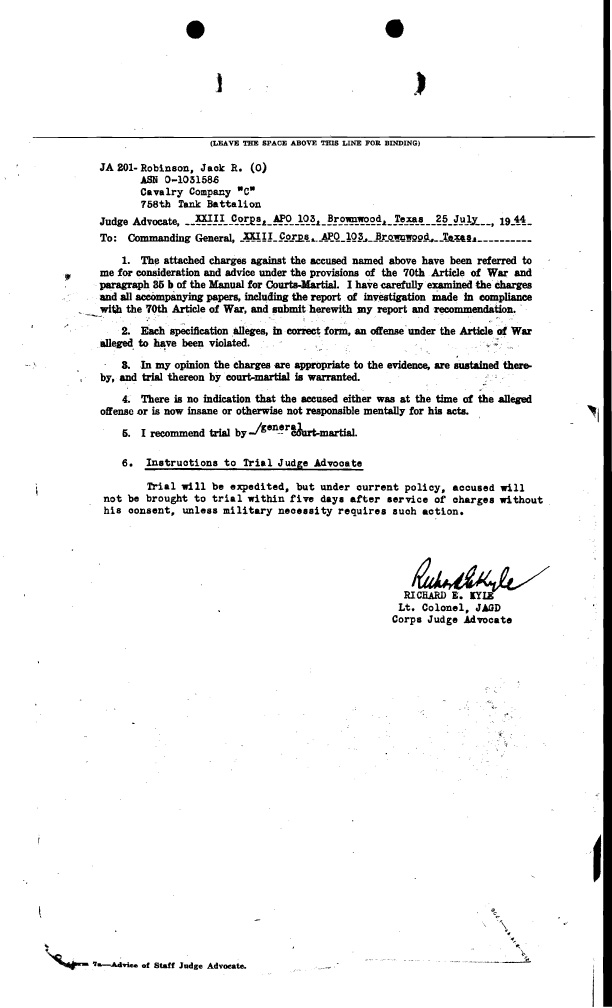

By the time of the hearing, the charges against Robinson were all for his alleged misbehavior at the station—after the incident on the bus.

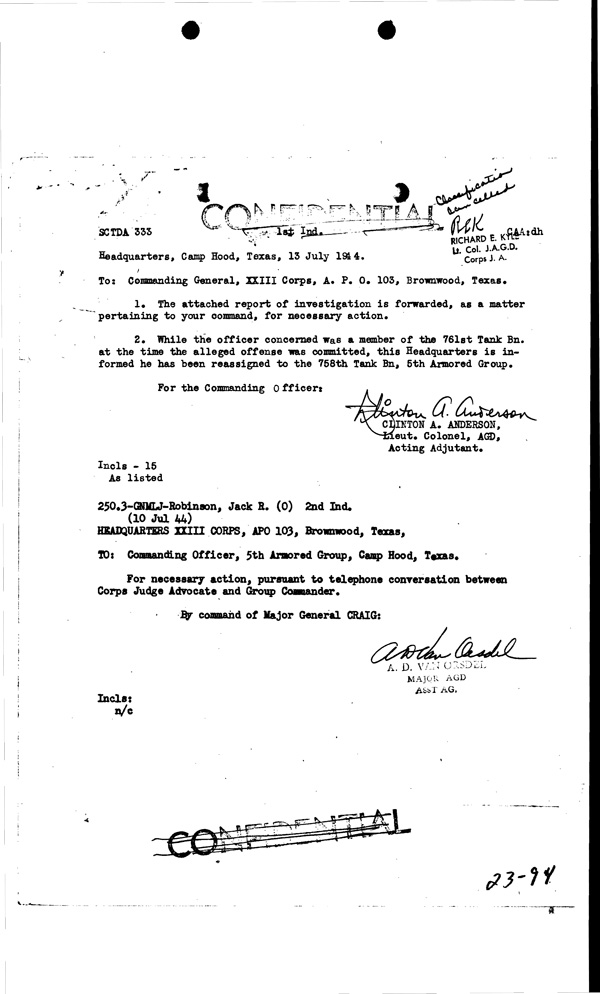

After Col. Paul L. Bates, commanding officer of the 761st, refused to sign the court martial papers, Robinson was transferred to the 758th Tank Battalion.

The court martial papers were signed once Robinson was with the 758th.

In an interview with Chuck Sasser, for his book Patton’s Panthers: The African-American 761st Tank Battalion In World War II, Bates’ wife, Taffy, confirmed the transfer’s goal: Robinson was “transferred from 761st, because Paul refused to sign court martial papers.”

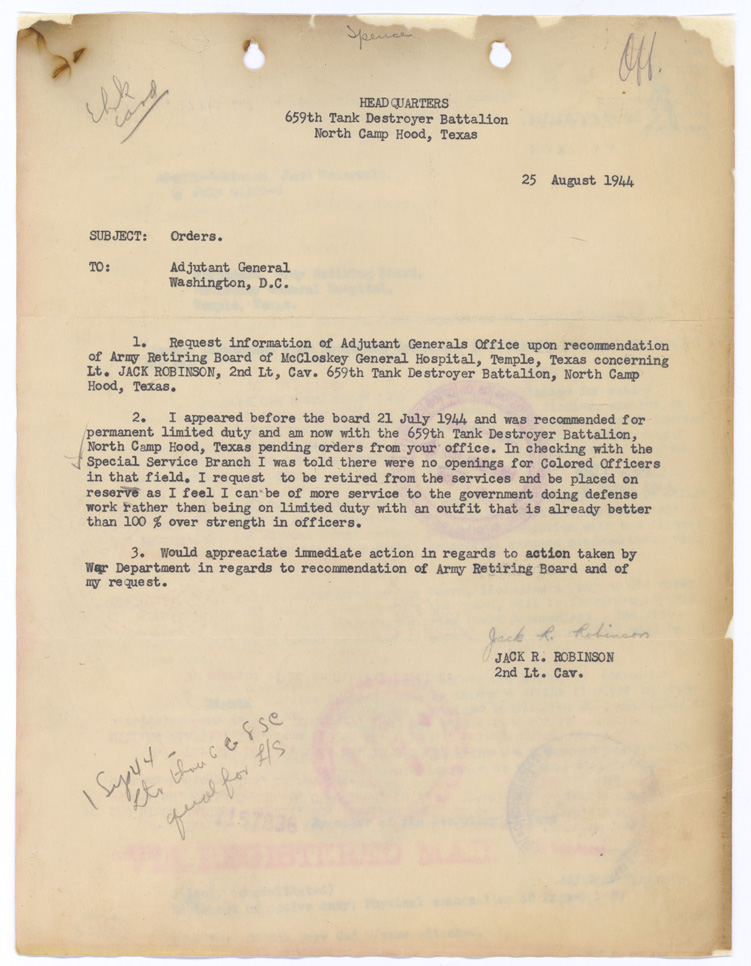

July 13, 1944, a document was sent to the Commanding General, XXIII, with an investigation report. It stated:

While the officer concerned was a member of the 761st Tank Bn. at the time the alleged offense was committed, this Headquarters is informed he has been reassigned to the 758th Tank Bn, 5th Armored Group.

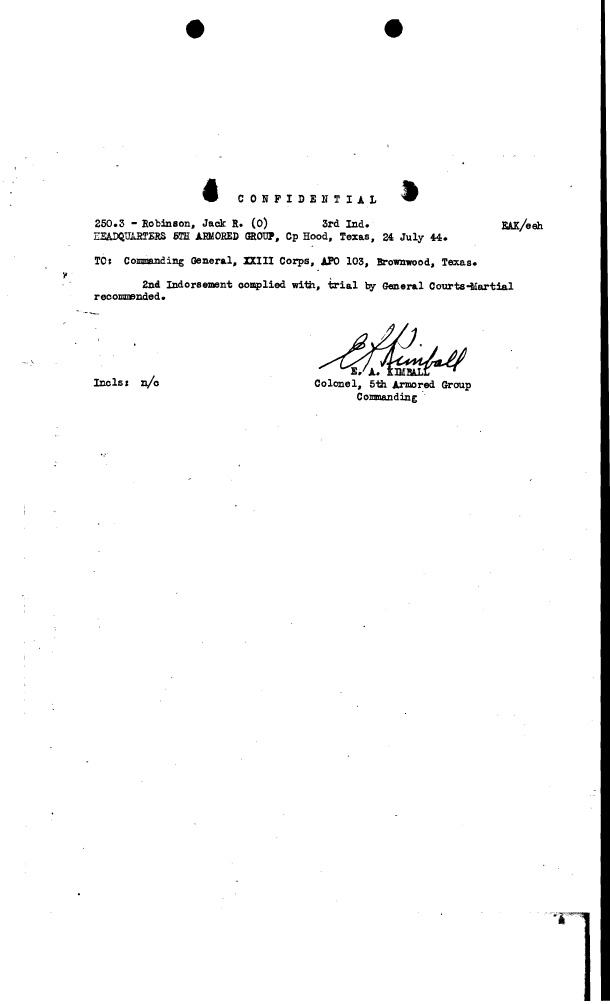

2nd Indorsement complied with, trial by General Courts-Martial recommended.

My first break was that the legal officer assigned to defend me was a Southerner who had the decency to admit to me that he didn’t think he could be objective. He recommended a young Michigan officer who did a great job on my behalf. He had a way of rephrasing the same question in so many clever ways that anyone who was lying would have a hard time not betraying himself.

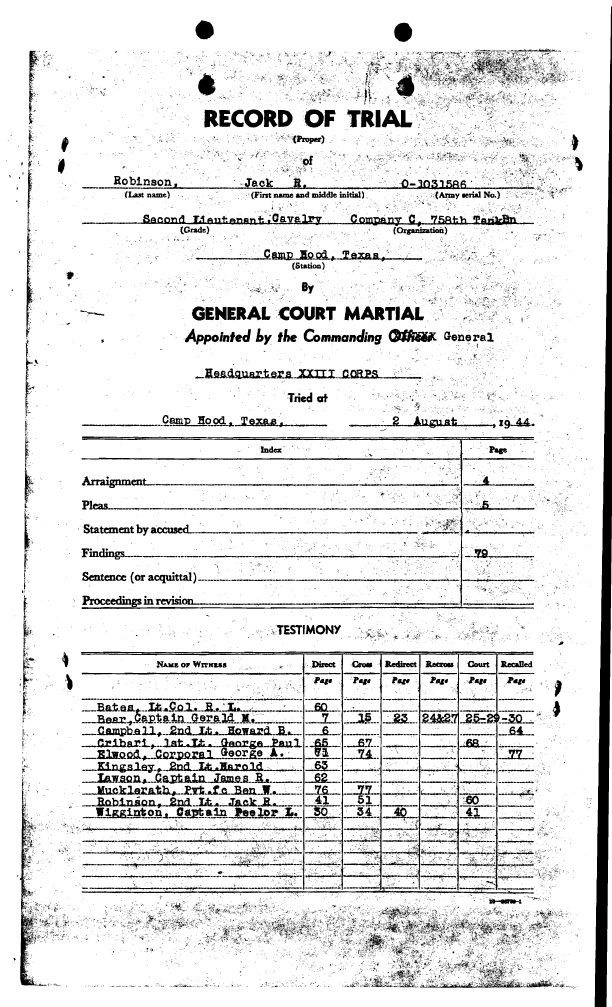

Court Martial Proceedings

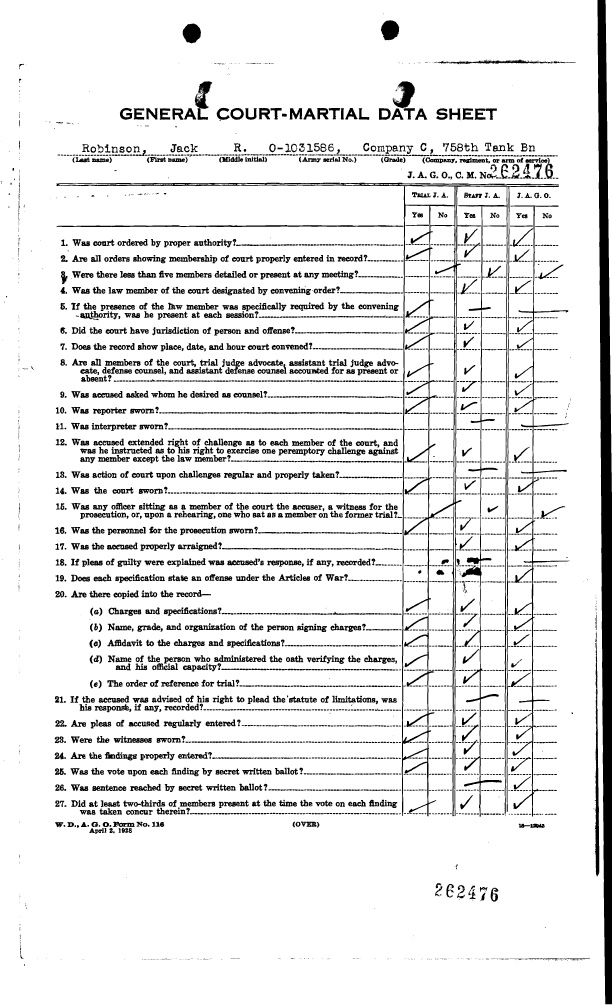

Credit: National Archives.

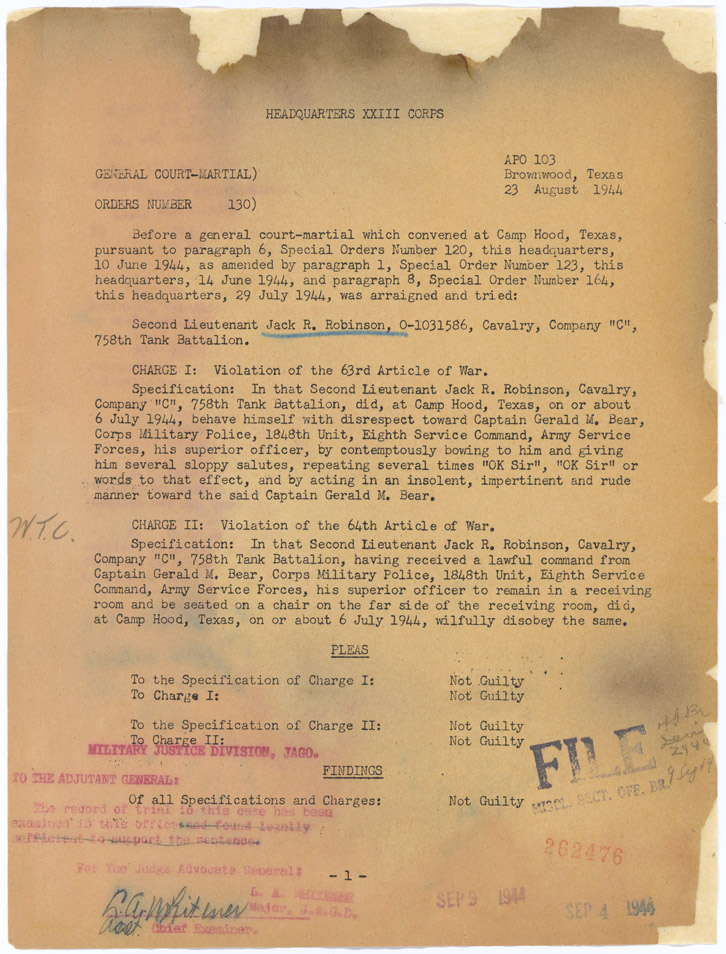

Credit: National Archives.

If Jackie Robinson had stayed with the 761st—and if the court martial had not taken place—he would have headed to Europe with the 761st and engaged “the enemy for 183 straight days in six European nations. No other unit fought for so long and so hard without respite . . . [and] participated in four major Allied campaigns, including the Battle of The Bulge.” (From Charles Sasser’s article “761st Tank Battalion: Patton’s Panthers Would Not Quit“, also posted today.)

Instead of battling in Europe, he fought equally important battles in the United States, fighting for equal rights while inspiring baseball fans around the world.

Thank you to the U.S. Army Legal Services Agency for providing copies of the court martial documents included in the above article.

CALLIE OETTINGER was Command Posts’ first managing editor. Her interest in military history, policy and fiction took root when she was a kid, traveling and living the life of an Army Brat, and continues today.