by Susan Ronald

Condé Nast might have wondered why a publisher should feel like the ringmaster of a circus that would put Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey’s to shame. True, he aimed to create the “most excellent and stunning greatest show,” albeit in the publishing world. Did that mean he was expected to tame and shackle his employees to prevent them from behaving like wild animals? He would have been discomfited by the image racing through his mind. He was a quiet, reflective sort of chap, never garrulous or given to outbursts of bad temper.

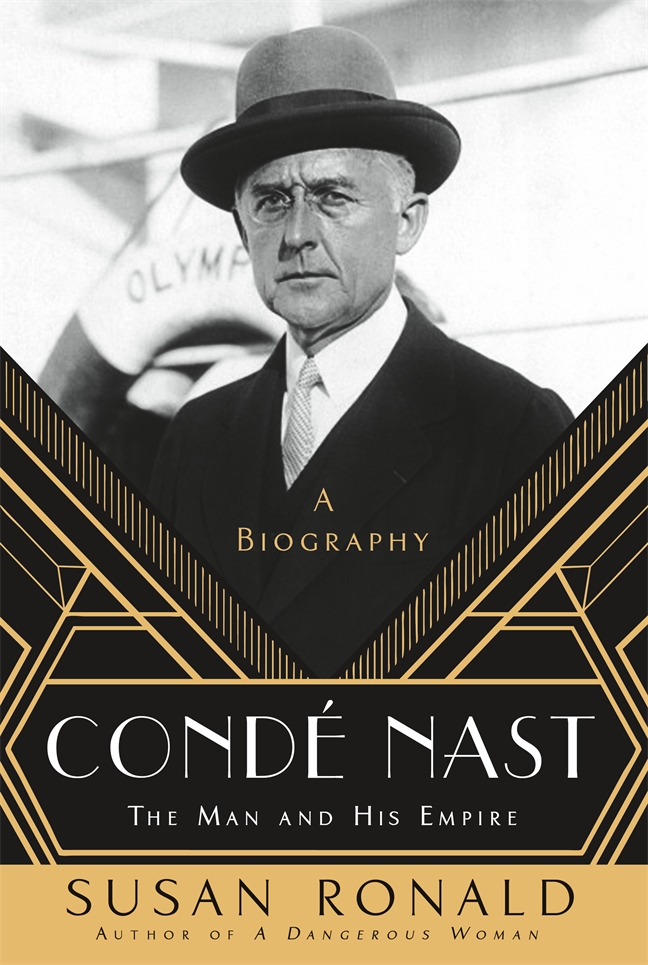

Though middle-aged, the forty-six-year-old Nast was still deemed handsome, with his even features, slim physique, and perfect posture. Some thought he was a bit bankerish with his wire-rimmed pince-nez, slightly receding hairline, and immaculately tailored three-piece suits. He was noted for his measured, gentlemanly manner, his numeracy, and his careful management style. Those who didn’t know him well thought he was standoffish. Others were floored by his incredible eye for detail. Above all, Condé was painfully shy and always mindful of his coveted place in New York high society. But a ringmaster? Never. . .

Of course he wanted the best in every field—illustrators, photographers, designers, writers, editors, layout people, and even advertisers. How else could he craft the best publications? Why, even his dear friend and editor in chief at Vanity Fair, Frank Crowninshield—everyone’s favorite raconteur—was guilty of high jinks, not to mention of poaching top talent from Condé’s cash cow, the highly successful Vogue.

As far back as the spring of 1915, Edna Woolman Chase, Condé’s editor in chief at Vogue, complained that Frank had his eye on “a small dark-haired pixie, treacle-sweet of tongue but vinegar- witted” who was working on captions and special features. One of her first pieces was about houses, Condé recalled, and was cleverly titled “Interior Desecration.” It made a fair few avant-garde interior designers turn away in shame. This woman was courageous, too. She even dared to become a lab rat for her feature article “Life on a Permanent Wave”—when perms were still hazardous and took an entire day hooked up to heated electric rods after the hair was soaked in a reagent (usually cow urine and water or caustic soda) to show results. The pixie’s name was Dorothy Rothschild. Within the year she became Dorothy Parker.

Condé had to smile at the memory. Of course Dorothy was too witty to remain the writer of special features and punchy one-liners like “From these foundations of the autumn wardrobe, one may learn that brevity is the soul of lingerie.” At times she borrowed from nursery rhymes, as when she hoped to tweak the noses of Vogue readers: “There was a little girl who had a little curl, right in the middle of her forehead. When she was good she was very very good, and when she was bad she wore this divine nightdress of rose-colored mousseline de soie, trimmed with frothy Valenciennes lace.” The suggestion that Vogue readers might actually have sex was anathema to the Palm Beach and Newport sets, and the offending quip was deleted at the proof stage.

Although Vanity Fair’s editor, Frank Crowninshield (called “Crownie” by his staff and close friends), was the quintessential Edwardian gentleman, he was the first to truly admire Dorothy’s way with words. So he duly poached the quiet, little, seemingly unassuming lass from Vogue. What else could he do? He adored her humor, and in 1915, together with George Shepard Chappell, the three of them wrote High Society: Advice as to Social Campaigning and Hints on the Management of Dowagers, Dinners, Debutantes, Dances and the Thousand and One Diversions of Persons of Quality. Their entertaining jests were illustrated by the pen-and-ink drawings of Anne Harriet Fish, the internationally famous artist for The Tatler and Vanity Fair in London.* Born in Bristol, England, “Fish,” as she was known to every witty household, was adored on both sides of the Atlantic. Still, she wasn’t the problem in managing his circus, Condé ruminated.

On her own perhaps Dorothy hadn’t been at fault? Then Condé thought back to his private assistant, Albert Lee, and his daily, almost religious, tracking of the Allied forces in the Great War on a huge map of France taped to the office wall. Lee painstakingly set the battle lines, as reported daily in The New York Times, in colored pins back and forth across no-man’s-land. (Just how he charted the infinitesimal movements by the yard, meter, or foot is anyone’s guess.) Being an inveterate biter of the hand that tossed her tasty morsels to write about, Dorothy taunted the poor man by dashing into Vogue’s offices early in the morning and devotedly rearranging Lee’s weary armies. While Lee eventually suspected that German spies had invaded Vogue, Frank pounced like any decent predator, and enticed Dorothy to soar under his wing, proclaiming, “Her perceptions were so sure, her judgment so unerring, that she always seemed to hit the centre of the mark.”

The fact was that Frank, too, adored practical jokes. An arch-player of many pranks, he had rather notoriously—and repeatedly—tied black thread to the legs of chairs in the guest bedrooms of country mansions where he was staying, then slipped the end of the thread out the bedroom door. When its occupant prepared for bed, the chairs would suddenly move, causing its mystified resident to either swear off alcohol or believe that the house was haunted.

It should have come as no surprise to Condé that Frank encouraged Dorothy’s antics. Life at Vanity Fair was more akin to a kindergarten than editorial offices—except of course for the crap games. Why, Frank even proudly called his private office “a combined club, vocal studio, crap game, dance-hall, sleeping lounge and snack bar.” Its very informality bred the utter chaos on which the magazine mysteriously thrived. Crowninshield introduced America to modern art and artists like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, as well as modern women writers like Colette and Dorothy Parker. A New York club man par excellence, Frank was one of the founders of the Coffee House, an antidote to the stuffy— but necessary—Knickerbocker Club.

Despite Frank’s inclination to mirth, Condé reflected, the issue was not with his friend, or even with Dorothy. It was that wisecracking cocktail of a trio he had hired at Vanity Fair: Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, and that gentle beanpole of a man, Robert Sherwood. What lunacy had possessed him to hire Benchley as his managing editor? Did he really believe Benchley might feel some responsibility to write those “serious” articles at Vanity Fair as originally promised? Condé had been fooled by Benchley’s Boy Scout appearance and good manners, his sandy—if thinning— hair, pale-blue eyes, serviceable off-the-rack suits from Rogers Peet, and, naturally, his sensible galoshes. Benchley didn’t swear, smoke, or drink back then, either. He was married and lived in Westchester County with his wife and young son. As for Sherwood, nicknamed “Sherry,” Condé should have known that anyone that tall—six feet seven** in his stockinged feet—and who wore his straw hat at such a jaunty angle would be trouble.

Can you hear Condé’s sigh across the past century? Well, Benchley’s pledged “serious” articles that got him the job in the first place turned out to depict the funereal world of the undertaker. And why should Benchley’s hobby for the gruesome, if practical, netherworld have been taken up quite so enthusiastically by Dorothy? It added insult to injury that Condé Nast Publications paid for Benchley’s subscriptions to their macabre reading—Casket and Sunnyside magazines. Sunnyside had, according to Dorothy, a joke column called—steel yourself now—“From Grave to Gay” that particularly tickled her fancy. “I cut out a picture from one of them, in color,” Dorothy recalled, “of how and where to inject embalming fluid, and hung it over my desk until Mr. Crowninshield asked me if I could possibly take it down. Mr. Crowninshield was a lovely man, but puzzled.” Puzzled? Actually, Frank recalled that there was a ghastly parade of color photos of cadavers in various states of preparedness for the grave, and ordered Dorothy to take them down. Perhaps she could replace them with prints by the artist Marie Laurencin instead?

Bluntly put, both Condé and Frank thought the trio’s daily imbroglios and prolonged lunch hours at Childs Restaurant had become too routine and must stop. Dorothy herself would write later that they were behaving “extremely badly.” So the long-suffering Condé asked his vice president, Francis Lewis Wurzburg, to strictly enforce the company’s code of punctuality. Everyone, without exception for rank or talent, must comply. The tenderhearted, loyal Wurzburg obliged, sending around a memo that all employees were to be at their desks at nine o’clock sharp. That meant at their desks. Not chatting in the corridors. Not loitering in the cloakrooms. Cards, the size of normal playing cards, were duly printed and handed out to would-be offenders, demanding that they state their reasons for their tardiness.

Benchley was the first to fall foul. Arriving eleven and a half minutes late, he found the card neatly placed on his desk. Applying himself to the task with vigor, Benchley rolled up his sleeves and began writing his sorrowful tale of the missing eleven and a half minutes. Wasn’t the office deafened by the roar of the Hippodrome’s*** elephants as they broke loose shortly before nine that morning? “A clutch, a gaggle, a veritable herd of elephants came trumpeting from the Hippodrome, shouldering their way through Forty-fourth Street” and rampaging across Sixth Avenue. “Frantic guards came rushing after them, pressing all passing civilians into a posse to help in the round-up.” It was worse than herding cats at a crossroads, Benchley plowed on. “The first thing I knew I had been swept up to West Seventy-second Street,” Benchley wrote. “Some of the animals had been trapped; others were still at large.” Just imagine the pandemonium, Benchley exclaimed in ever-smaller letters curling around the edges of the card. Down they went to West End Avenue and the Hudson River docks, where the elephants tried to “board the boats of the Fall River Line” before they were finally herded back “to the Hippodrome, thereby averting a major marine disaster” but unfortunately causing him to be eleven minutes late for work.

If Condé blamed himself for their shenanigans, he was selling himself short. He was a pioneer, a visionary, a prospector who had found gold in promoting the “New Woman.” Since the 1890s the New Woman had adorned the pages of novels in Europe and North America as sports-loving, defiant, intelligent, an original modern vision of feminism, equal to any man working in offices, factories, and workshops. It was she who demanded social and political reform, and the right to vote.

Condé was the first to bring European style, culture, and the modern arts to America with each issue of his publications, widening the country’s horizons from its parochial perspectives. He had broken the glass ceiling by promoting Edna Woolman Chase—a woman of no experience—from a gofer to top management (something many employers still fail to do today). Soon enough he would be credited with creating café society; throwing the most awesome parties; finding young, untested talent from the international arena who would change the way we think; and becoming one of the foremost Americans influencing the export of the country’s can-do attitude, know-how, products, fashion, and style to the world. He wrote the first paycheck ever for the British playwright Noël Coward. Aldous Huxley, Compton Mackenzie, and P. G. “Plum” Wodehouse were on his staff. He was the first to publish Edna St. Vincent Millay (writing as Nancy Boyd), Donald Ogden Stewart, Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, e. e. cummings, and many more in any magazine. Condé was also a high-tech pioneer—promoting cutting-edge technologies in photography and printing, making his publications a byword for all that was modern.

So what did it matter that he had left Benchley in charge of Vanity Fair, assisted by Dorothy and Sherwood, while he and Frank swanned off to Europe for two months? So what if Edna was also journeying to England and beyond for Vogue at the same time? Worrying was part of his job, and he couldn’t help but fret as their ship the Aquitania sailed for Europe. It made him uncomfortable to leave the circus animals in charge of his greatest gift to fun-loving, hard-thinking New Yorkers, Vanity Fair. But, the Great War was over, and court must be paid to all those in France and Brit- ain who had suffered so cruelly. A delay in their plans was frankly impossible. Besides, truthfully, what real damage could the trio do in a mere sixty days, or two editions of Vanity Fair? Condé wasn’t an unreasonable man, and even if the battle lines had been drawn, for now he must let them win the skirmish.

*This Vanity Fair was the political satirical magazine published in London.

**2.04 meters.

***The Hippodrome, at the time the world’s largest theater, was located diagonally across from the Vogue and Vanity Fair offices, then located at 19 West Forty-fourth Street, at the corner of Sixth Avenue (“Avenue of the Americas” to tourists).

Born and raised in the United States, SUSAN RONALD is a British-American biographer and historian of several books, including A Dangerous Woman, Hitler’s Art Thief, and Heretic Queen. She lives in rural England with her writer husband.