by Jack Kelly

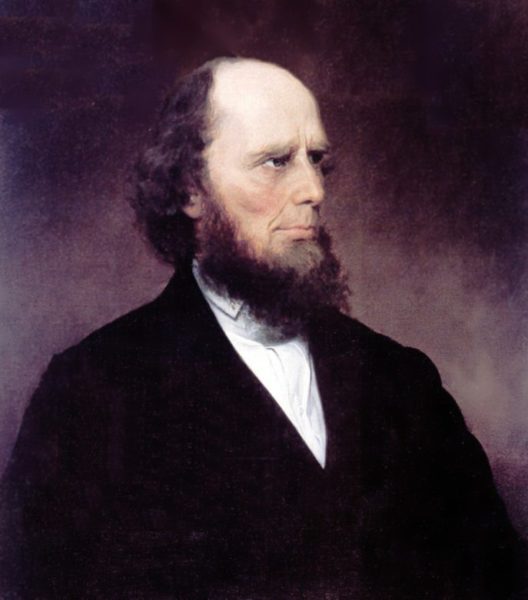

Charles Finney and the Erie Canal

Billy Graham ‘s long career invites comparisons with America’s greatest evangelists, including Dwight Moody in the late nineteenth century and Billy Sunday in the early twentieth. But Graham’s real roots reached back to the consequential career of Charles Grandison Finney, who gave the Christian revival the shape that it would retain for two centuries. In the process, Charles Finney took the dour Puritan orthodoxy of the day and turned it into a dynamic, optimistic and decidedly American faith.

In the early 1800s, American churches were cautiously edging away from the most severe of the Calvinist precepts. For almost two hundred years, Puritans had pushed the notion that humans were utterly depraved and were predestined for heaven or hell regardless of their good works. Erudite clergymen, decorous services and yawn-inducing preaching were standard fare.

The Constitution’s prohibition on federal support of religion opened a vibrant new “market” in religious faith. As the nineteenth century began, itinerant Methodist preachers began to range along the frontier, offering pioneers and country people a more hopeful faith based on an “inner light.” The camp meetings they and others organized featured hell-and-brimstone preaching and wild manifestations of spirit. Attendees groaned, trembled, shouted out loud and fell on all fours to bark Satan up a tree.

Charles Finney had grown up on the frontier and had studied to become a lawyer. Having embraced Christ in a spasm of emotion, he dropped the law, took a quick course in theology, and learned his craft preaching to snowbound Christians in the western Adirondack Mountains of New York. He brought what he called his “methods” to the bustling Erie Canal corridor in the 1820s. He was to be the man who made intense religious enthusiasm respectable in America.

Charles Finney encountered fierce opposition from the established clerics of New England. He was degrading Christianity, they said, encouraging fanaticism among the faithful. Those who came to Jesus in burst of enthusiasm could turn away just as quickly. Charles Finney answered that souls were descending into Hell while the Church slept. Action was needed, not passivity. His enormous success in the 1830s won the day.

Read more about the 5 Technological Breakthroughs of the Erie Canal here

Many of the techniques employed by Graham were originated by Charles Finney. Rather than explicate nuances of theology, Finney pointed his finger and called congregants sinners to their faces. He spoke of Hell as a real and terrifying danger. He pleaded with believers to take the steps needed to get right with the Lord.

A revival, Charles Finney taught, was something that an evangelist could engineer, not a boon he should wait for. He preached in a city’s churches daily for weeks, sometimes months. He organized prayer and inquiry meetings and trudge from house to house, identifying and encouraging converts. Graham’s career was likewise marked by Herculean efforts through the 417 crusades he organized over more than half a century.

Charles Finney understood how to manufacture social pressure to accept the Lord. He encouraged family members to twist the arms of loved ones who were in danger of damnation. He focused on prominent and wealth people in town, knowing if they converted, others were likely to follow. He made religion fashionable. Graham also made efforts to attract the influential, including presidents.

The key was to get the sinner to act. Stand up, Finney would urge. Come down to a pew reserved in front. On this “anxious bench,” potential converts agonized over their faith as their fellow worshipers prayed them toward conversion.

Billy Graham, like generations of evangelists, absorbed the lessons of Charles Finney’s Lectures on Revivals of Religion. He kicked off his own career with a revival in Los Angeles during the summer of 1949. Scheduled for three weeks, it went on for two months. Graham did everything in his power to make religion the talk of the town. He succeeded in converting three thousand souls and never looked back.

Both Graham and Finney projected utter sincerity and an intense sense of urgency. “Never was a man whose soul looked out through his face as his did,” a follower said of Finney. Graham was blessed with a penetrating gaze and a face that radiated earnest conviction. He was a master of inducing his listeners to respond to the “altar call,” to come forward and affirm their faith.

Both men, while spreading God’s Word, became involved in politics. Charles Finney was inveigled in campaigns for temperance and Sabbath-keeping. He supported the abolition of slavery long before it became a popular cause in the North. Graham was drawn by the anti-communism of his own day into an association with the presidency of Richard Nixon.

“Few men have had such a profound impact on their generation as Charles Grandison Finney,” Graham wrote in an introduction to a book about the great evangelist. “Through his Spirit-filled evangelistic ministry, uncounted thousands came to know Christ, resulting in one of the greatest periods of revival in the history of America.”

Graham, too, touched countless thousands of lives during his long ministry.

Jack Kelly is the author of Heaven’s Ditch: God, Gold, and Murder on the Erie Canal (St. Martin’s Press), a lively account of the canal and the many excitement generated along its banks. He is a journalist, novelist, and historian, whose books include Band of Giants, which received the DAR’s History Award Medal. He has contributed to The Wall Street Journal, and other national periodicals, and is a New York Foundation for the Arts fellow. He has appeared on The History Channel and been interviewed on National Public Radio. He spent his childhood in a town in the canal corridor adjacent to Palmyra, Joseph Smith’s home. He now lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.