by Giles Milton

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke viewed his caravan with the sort of affection that most men reserve for their wives. He polished it, tinkered with it and buffed up its cream paintwork with generous quantities of Richfield Auto Wax.

More than fourteen feet in height, it stood taller than a London double-decker and its low-slung chassis was a revolutionary piece of engineering. But the real joy of Cecil’s creation was its luxurious interior. It came with lavatory, bedrooms and an en suite bathroom. It had hot and cold running water and its own home-built generating plant. It also had a well-stocked bar. Little wonder that Cecil referred to it as his ‘Pullman of the road’.

He had built it in his workshop behind the family home in Bedford. At weekends he would hook it to the family charabanc and take it on road trials, hurtling through the local country lanes while his wife Dorothy clutched the dashboard and their two sons, John and David, made mischief in the back.

The young lads yelped with delight when their father announced that he was taking the family off to north Wales. There were a few tense moments as they bid their farewells to Bedford: Cecil had added a new bedroom on the caravan’s first floor and the vehicle was now so tall that he had to stop at every bridge and check that they had the necessary clearance.

Once they were out on the open road, obstacles such as bridges were quickly forgotten. He got ‘rather blasé’ and simply ‘charged at every bridge he came to – fortunately without any real damage’. The fact that young John and David were larking about on the roof of the caravan, ‘getting a fine view of the countryside’, did not seem to bother him one jot.

Cecil ‘Nobby’ Clarke had set up his company, LoLode (the Low Loading Trailer Company) in the late 1930s, with himself as principal designer and Mrs Clarke as company secretary. All LoLode’s caravans came equipped with a unique suspension system that promised passengers a smoother ride than any other caravan on the road. It was a promise in which Clarke took considerable pride, for he was the designer, the engineer, the architect and the mechanic.

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke was portly and bespectacled, a lumbering gentle giant with heavy bones and a mechanic’s hands. Half boffin, half buffoon, he had more than a touch of the Professor Branestawm about him. An enthusiastic smoker and fervent patriot, he was viewed by his neighbours with affection tinged with humor: ‘the embodiment of an ideal,’ thought one, ‘always in his own way striving after the betterment of society.’ In Cecil’s case, the ‘betterment of society’ meant building more comfortable caravans. Those Bedford neighbours would smile knowingly to one another as they watched ‘Nobby’ buffing the paintwork of his beloved vehicles, unaware that he had the hands of a magician and the brains of a genius.

Caravans were not the only thing that quickened his pulse. As a young volunteer in the First World War, he had got himself attached to a pioneer battalion that specialized in explosives. He acquired an early taste ‘for making loud bangs and won himself a Military Cross for his part in helping to blow the Allies to victory in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. Although he had made the transition back to civilian life with greater ease than many of his comrades-in-arms, there was a part of him that continued to harbour dreams of making loud bangs.

In the summer of 1937, Cecil Vandepeer Clarke had submitted a LoLode advertisement for inclusion in his favourite magazine, Caravan and Trailer. Describing his vehicle as a ‘three berth living van of the most advanced design’, it even had a servants’ quarters at the rear.

The editor of Caravan and Trailer was a man named Stuart Macrae, an aviation engineer by training who had fallen into the world of journalism by accident rather than design. He was intrigued by the pictures of Clarke’s outlandish creation and decided to pay a visit to Bedford, taking the day off work in order to meet him.

Listen to more incredible unknown history from Giles Milton’s podcast now available on iTunes

His first impression was one of disappointment. Cecil Vandepeer Clarke was ‘a very large man with rather hesitant speech, who at first struck me as being amiable but not outstandingly bright’. He was soon forced to revise his opinion. Clarke had an expanding brain that functioned like an accordion. He sucked in ideas, mixed them together and then expelled them as something altogether more melodious. Where most people saw problems, he saw only solutions.

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke opened up the yard behind the house in order to show Macrae ‘his latest brain child’. It was huge, far bigger than it looked in the pictures, and ‘streamlined into the bargain’. Macrae was stunned: he felt as if he were looking at ‘something from the future’.

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke proposed a spin round the Bedfordshire countryside, with himself at the wheel and his guest in the caravan. Macrae made himself comfortable on the Dunlopillo cushions and got happily sloshed on the various bottles in the well-stocked bar. ‘And as there were no breathalizers in those days’ – nor any stigma attached to drink-driving – he was able to drive back to London without fear of being caught by the police.

When he was back at work the following morning, somewhat sore of head, he wrote a fulsome article about Clarke’s extraordinary prototype. And there the story might have ended, for Stuart Macrae quit his job at Caravan and Trailer soon afterwards and took up a position as editor of Armchair Science.

But one morning in the spring of 1939, Macrae’s secretary answered the phone to a most mysterious caller. ‘There’s a Geoffrey Somebody on the phone,’ she called across the office: he was calling on a matter of some urgency. Macrae took the call and found himself speaking to someone called not Geoffrey, but Millis Jefferis.

Jefferis said that he was keen to find out more about one of the items featured in the latest issue of Armchair Science. ‘You have an article about a new and exceptionally powerful magnet. I want full information about this magnet right away, please.’

Macrae was taken aback by the caller’s gruff manner and asked to know more. ‘Well it’s a bit awkward,’ admitted Jefferis. ‘I’m not at liberty at present to tell you what this is about.’ He suggested that they meet for lunch and talk it over in private.

Forty-eight hours later, Macrae found himself in the Art Theatre Club, seated opposite one of the most extraordinary individuals he had ever met. Millis Jefferis had ‘a leathery looking face, a barrel-like torso and arms that reached nearly to the floor’. To Macrae’s discerning eyes, ‘he looked like a gorilla’. But when the gorilla opened his mouth, ‘it was at once obvious that he had a brain like lightning’.

Jefferis explained that he worked for a highly secret branch of the War Office, one that specialized in intelligence and research. With international tensions on the rise, he had been tasked with devising unconventional weaponry that might be needed in the near future.

His interest in magnets stemmed from a revolutionary underwater mine that he was trying to develop. Its explosive charge was coated in magnets and equipped with a time-delay detonator. The idea was that it ‘would stick to the side of a ship when placed there by a diver, and go bang in due course and sink the said ship’.

The need for such a weapon was real and urgent. Less than six months earlier, in the winter of 1938, Hitler had launched his Plan Z, the immediate and dramatic strengthening of the German Kriegsmarine. The plan envisaged the construction of 8 aircraft carriers, 26 battleships and more than 40 cruisers, as well as 250 U-boats. Britain was in no position to compete in such a naval arms race and was faced with having to find a more creative way to redress the balance. Senior figures in the War Office and Admiralty decided that sinking German ships would be more cost-effective than building British ones.

But Jefferis faced an insurmountable problem. He was unable to find magnets that would function underwater and was also too busy to build a reliable time-delay detonator. Without one, he knew that his half-built magnetic mine wouldn’t work.

After a well-lubricated lunch finished off with goblets of brandy, Macrae rashly offered to take over the project. One of his previous jobs had been designing bomb-dropping mechanisms for low-flying aircraft. He was more than willing to tackle this new challenge. Jefferis was surprised by Macrae’s offer, but glad to accept. He said that ‘he had a private bag of gold from which he could at least pay my expenses’.

It was only later in the day, when the mists of brandy had cleared, that Macrae began to regret his decision. He didn’t have a clue how to build a magnetic mine and nor did he have a workshop in which to experiment. As he pondered how best to proceed, he was suddenly reminded of Cecil Vandepeer Clarke, his prototype caravan and his Bedford garage. He called LoLode and, without revealing who he was or why he was calling, arranged for a meeting. The following morning, he pitched up at 171 Tavistock Street with a bagful of magnets and a cry for help.

* * *

Stuart Macrae’s visit to Cecil Vandepeer Clarke’s Bedfordshire workshop came at an ominous moment in international relations. A few days after Hitler had marched his storm-troopers into Bohemia and Moravia, he ordered them into the Baltic port of Memel, in Lithuania. Memel was a German-speaking enclave that had been detached from Germany after the First World War. Hitler had repeatedly denied having any designs on the port, but in the wake of his Prague triumph he demanded Memel’s capitulation. Lithuania’s Foreign Minister was faced with acceding to the Führer’s demands or risking a full-scale military invasion. He had little option but to agree.

‘A large, blazing swastika announces to the traveller that the administration of Memel has changed hands.’ So wrote an English journalist who got the scoop of his life by happening to be in the port when the storm-troopers marched in. ‘In village windows, candles flicker and a Brownshirt parade continued till a late hour.’

Hitler arrived in triumph the following morning and welcomed Memel’s overwhelmingly German population into the Fatherland. Ominously, he declared that the Third Reich was ‘determined to master and shape its own destiny, even if that did not suit another world’.

The Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, continued to chase after a peaceful solution, even after the illegal annexation of Memel. ‘I am no more a man of war today than I was in September,’ he said in reference to the previous year’s Munich Agreement that had handed the Sudetenland to Hitler. But not everyone agreed with his policy of appeasement, and some were starting to prepare themselves for more direct action. Among them were Stuart Macrae and Cecil Vandepeer Clarke.

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke was delighted to renew his acquaintance with Macrae, for the two men had got along famously when they had first met. This time around, Macrae was invited into the Clarke family home and offered a snack. ‘Sweeping a number of children out of the living room,’ he later wrote, ‘which also had to serve as an office, he filled me up with bread and jam and some awful buns and then got down to business.’

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke showed characteristic enthusiasm from the outset, informing Macrae that lethal weapons could be constructed from the simplest pieces of equipment. Macrae was nevertheless surprised to find that their first port of call was Woolworths on Bedford High Street. Here, they bought some large tin bowls. Next, they visited a local hardware store and bought some high-powered magnets. And then they took everything back to Tavistock Street, where Clarke created ‘an experimental department by sweeping a load of rubbish and more children off a bench’.

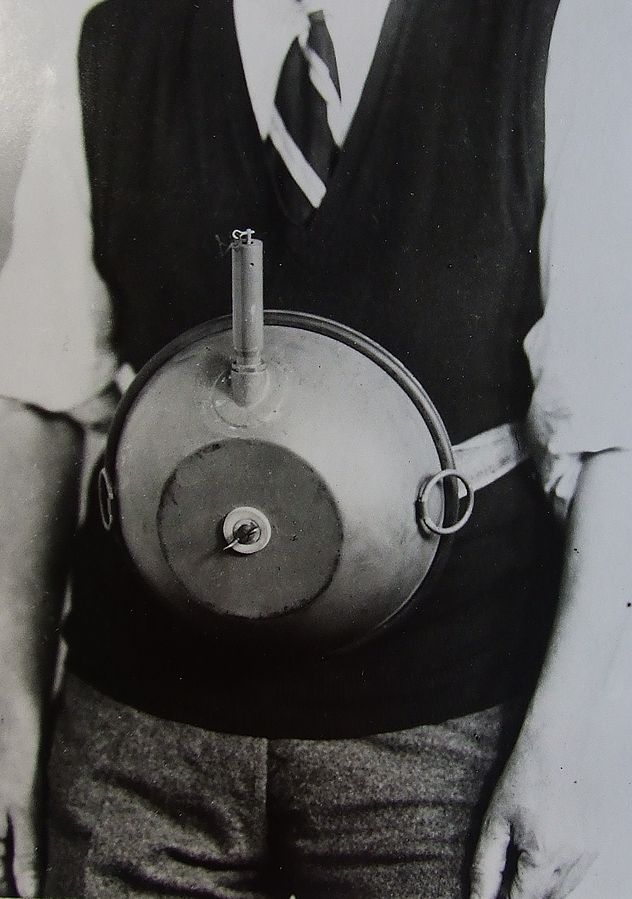

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke took to the task in hand with undisguised relish. He commissioned a local tinsmith to make a grooved metal ring that could be screwed on to the Woolworths’ bowl. When this was done, he poured bitumen into the ring and used it to secure the magnets. His idea was to fill the bowl with blasting gelatine and then screw on a makeshift watertight lid.

The key factor was to make the mine light enough to stick to the side of a ship. ‘Eventually after using up all the porridge in the house in place of high explosive for filling, juggling about with weights and dimensions, and flooding Nobby [Clarke’s] bathroom on several occasions, we got this right.’

It was one thing to design a weapon, quite another to make it work. Clarke and Macrae took themselves off to Bedford Public Baths and, after explaining to the janitor that they were conducting vital military research, obtained permission to use the main swimming pool once it was closed to the public.

They propped a large steel plate in the deep end and then strapped the welded Woolworths’ bowl to Clarke’s ample stomach. ‘Looking as if he were suffering from advanced pregnancy, he would swim to and fro removing the device from his belt, turning it over and plonking it on the target plate with great skill.’ It worked perfectly. The mine stuck to the metal plate each time and remained securely in position.

There was just one thing missing. A bomb could not explode without a detonator, and the detonator for this particular weapon needed to be absolutely reliable. If it exploded too early, it risked killing the underwater swimmer.

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke set about designing a spring-loaded striker that was held in a cocked position by a soluble pellet. When the pellet dissolved in the water, the striker would hit the detonator and the bomb would explode. But finding a suitable pellet proved difficult. The two men tried all manner of devices but none of them worked in a satisfactory fashion. Pellets made of powder dissolved too quickly. Pellets that were too compact didn’t dissolve at all.

In the end, it was Cecil Vandepeer Clarke’s children who inadvertently provided the solution. As Cecil swept them off his workbench for the umpteenth time, he upset their bag of aniseed balls and dozens of sweets rolled across the floor. Macrae popped one into his mouth and began playing with it on his tongue. As he did so, he was struck by how it shrank in size with absolute regularity. It was exactly what was needed. Cecil Clarke rigged up his strikers to the children’s aniseed balls while young John Clarke looked on crossly. Each spring-loaded striker was placed in ‘a big glass Woolworth’s tumbler’ and put through a series of tests until Clarke had worked out the exact time it took for the sweet to dissolve.

‘Right, that’s 35 minutes,’ he would shout across the living room. Sure enough, the aniseed ball would slowly dissolve over the course of half an hour until the striker was suddenly released. There was no explosive charge, so the damage was confined to the glass, which invariably shattered and fell to the floor in pieces. Mrs Clarke spent her afternoon sweeping up fragments of broken glass.

The men were delighted that their idea had worked. ‘The next day the children of Bedford had to go without their aniseed balls,’ recalled Macrae. ‘For not wishing to be held up for supplies, we toured the town and bought the lot.’

The last remaining problem was to find a suitable means of storing their magnetic mine. It was essential that the aniseed ball be protected from damp, otherwise the mine risked exploding while in storage. Their solution was once again homespun but inventive: they pulled a condom over the striking mechanism and found that it formed a perfect damp-proof sleeve, expanding neatly over the various bumps and creases.

Thus it was that two middle-aged gentlemen found themselves walking around Bedford, going from chemist to chemist, buying up their entire stocks of condoms, ‘and earning ourselves an undeserved reputation for being sexual athletes’. Macrae neglected to record whether, nine months later, Bedford experienced any short-term spike in its birth rate.

Just a few weeks after his introductory luncheon at the Art Theatre Club, Macrae was able to show Millis Jefferis the prototype magnetic mine that had been given the provisional name of limpet. Jefferis immediately recognized Cecil Vandepeer Clarke’s weapon as a work of technical wizardry. For a little less than £6 (including labour), he had produced an explosive device that was lightweight, easy to use and devastatingly effective, one that had the potential to be a game-changer in time of war. For if a single diver equipped with a single limpet mine could destroy a single ship, then it stood to reason that a team of divers could destroy a fleet of ships. And that made it a very significant weapon indeed.

It was also extremely versatile. Its magnetic surface meant that it could be used to blow up turbines, generators, trains – anything, indeed, that was made of metal. It was the perfect weapon for sabotage, small, silent, deadly, and with a touch of dark mischief that particularly appealed to Jefferis.

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke returned to his caravans in Bedford, unaware of the fact that unknown men in clandestine offices were already planning his initiation into a world so secret that even most ministers in Whitehall knew nothing of its existence.

It was the very same world into which Joan Bright found herself entering on a seemingly unremarkable spring day in 1939.

Copyright © 2016 by Giles Milton

GILES MILTON is an internationally bestselling author of narrative nonfiction. His books include Nathaniel’s Nutmeg—serialized by the BBC—and seven other critically acclaimed works of history.