by Alex Landragin

It was a cool, grey spring day in Paris. I was standing in the Montparnasse Cemetery in front of the grave of the Romantic poet Charles Baudelaire, still a shrine to his many fans, who leave offerings of flowers, poems, and Metro tickets. I had a novel, which I’d already titled Crossings, laid out in pieces in my head, and Baudelaire – or Charles as I’d come to call him – played a crucial part in it. But I didn’t know how to bring the pieces together. I’d come here hoping to find the solution.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 France license.

Crossings is an amalgam of two stories that were bouncing around in my head a few years ago. One was the story of the final days of the German writer Walter Benjamin, who died escaping Nazi persecution at the beginning of 1940, carrying an unpublished work that subsequently disappeared. The second was a fictional tale I’d been told about by a teacher two decades earlier about an island whose inhabitants can swap bodies. When a European ship that ‘discovers’ the island sails away, it’s unclear who has left and who has stayed behind. That tale haunted me for decades before one blessed morning I had the insight that I could write a novel about what happened next – the story of the islanders who’d ‘stowed away’ in the bodies of European sailors. I also realised that if I combined the two stories, I could create an intricate and compelling hybrid story, using the conceit of ‘crossing’ to explore some of Walter Benjamin’s key concepts.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

But how was I going to fit these two stories together? The obvious answer was Charles Baudelaire and his lover and muse, the beautiful and enigmatic Jeanne Duval, who was a woman of colour with unknown origins, and whose story reflects many contemporary concerns. I knew Walter Benjamin had been fascinated by Baudelaire and his period – the 19th century – almost to the point of obsession. So I had three pieces of a puzzle spread out across time and space that needed a thread to combine them. Having never written a historical novel, there would be no short cuts writing this one. I knew that to find it I must move to Paris.

Cut forward to the spring day in front of Charles’ grave. Standing there, I felt closer to Charles than I did reading his poems and biographies. But I was no closer to the thread. I began exploring the cemetery. I knew the opposite corner of the graveyard was traditionally reserved for Jewish families, and because Walter Benjamin himself was Jewish I thought it might instructive to see it for myself. I was about halfway there, not far beyond the grave of one of my idols, Serge Gainsbourg, when out of the corner of my eye I saw something that brought me to a sudden, stunned stop. I was standing before a plinth of grey and pink mottled marble with an unusual inscription. It was not a family crypt, as most of the plots are in that cemetery, but an institutional one. The institution’s name was eerily à propos: La Société Baudelaire. Under these gilded words were the names of several people who’d been associated with it in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Their names were not related. My heart started beating faster – was this the thread I’d been looking for?

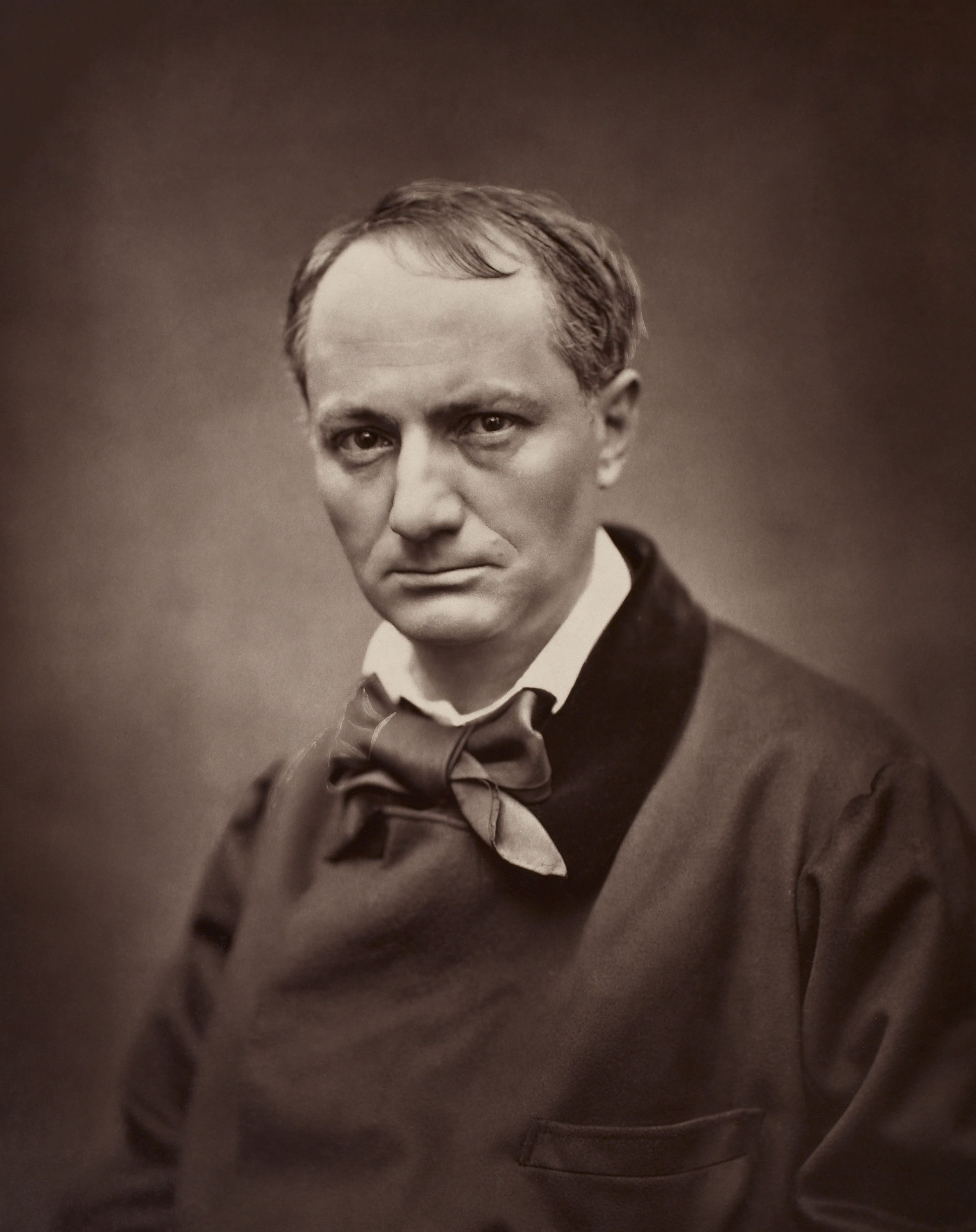

Charles Baudelaire by Étienne Carjat, 1863.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

That night, in front of my laptop, I searched for Société Baudelaire and found a website that seemed to have been designed decades earlier. By means of that website, I discovered a literary society with origins in the 19th century, when joining societies, clubs, and salons was considered the height of sophistication. Since fallen on hard times, the Société Baudelaire had once been a meeting-place for high-society types, including the famed fashion designer Coco Chanel.

I knew there and then that I had found what I had gone to the cemetery to find. From then on, the novel often seemed to be writing itself, using me as the conduit for its spiriting itself into existence. Of course, there was still a lot of work to do, countless hours to spend in the gigantic bunker that is the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, as well as half-a-dozen other libraries in Paris, London, and New Orleans. But from that moment in the cemetery, it felt like I wasn’t writing a novel so much as following a pre-existing trail of breadcrumbs. Many of the details I have just related went straight into the novel unchanged – even Coco Chanel makes an appearance as a femme fatale. Finally, I had my thread.

Alex Landragin is a French-Armenian-Australian writer. Currently based in Melbourne, Australia, he has also resided in Paris, Marseille, Los Angeles, New Orleans and Charlottesville. He has previously worked as a librarian, an indigenous community worker and an author of Lonely Planet travel guides in Australia, Europe and Africa. Alex holds an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Melbourne and occasionally performs early jazz piano under the moniker Tenderloin Stomp. Crossings is his debut novel.