dd

by Tasha Alexander

Few stories in the history of stories are better than that of Howard Carter discovering Tutankhamun’s tomb one hundred years ago on November 4. If it were fiction rather than fact, it would be wholly unbelievable.

Carter started working in Egypt when he was seventeen, eventually serving both as an excavator and as a member of the Antiquities Service. In 1905, he was embroiled in controversy after siding with native Egyptian guards who clashed violently with a group of French tourists. He’d never got along well with the wealthy visitors who swanned through Egypt and categorically refused to apologize to the Frenchmen. Instead, he resigned from his position and was left without a reliable income. It appeared that what had started as a brilliant career was coming to a crashing, disappointing end. For a few years, he was forced to cobble together a living as an artist. Then, when it seemed impossible that his fortunes would turn, the Fifth Earl of Carnarvon hired him to take charge of the excavations he was funding. Eventually, this took him back to the Valley of the Kings, the burial place of the ancient pharaohs.

On the surface, this sounds thrilling beyond measure. Theodore Davis, the last man who’d had permission to dig in the Valley, spent more than a decade there, excavating twenty-four tombs. In 1914, Davis retired, saying, “I fear that the Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted.” Was Carter taking over a hopeless job? For six years, that seemed to be the case; he discovered nothing significant. Carnarvon, who was running through his fortune, was ready to abandon the project, but Carter convinced him to finance one last short season. His patron agreed to let him continue for the last two months of 1922.

Very few people other than Carter had any faith in the scheme.

On November 1, Carter set to work clearing the remains of huts used by the men who had built the royal tombs. On November 4, he found stone steps, and everyone knew what stone steps in the Valley of the Kings meant: a tomb.

By the end of the next day, his team had cleared twelve of them, revealing the top of a door. A few weeks later, Carnarvon arrived and the excavation could begin in earnest. On November 24, enough debris had been removed to make visible the seals of the pharaoh Tutankhamun, who’d died in 1323 BCE. A few days later, Carter drilled into a door and poked a candle through into the room on the other side. When Carnarvon asked if he could see anything, he replied, “Yes, wonderful things!” He later wrote:

It was sometime before one could see, the hot air escaping caused the candle to flicker, but as soon as one’s eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another.

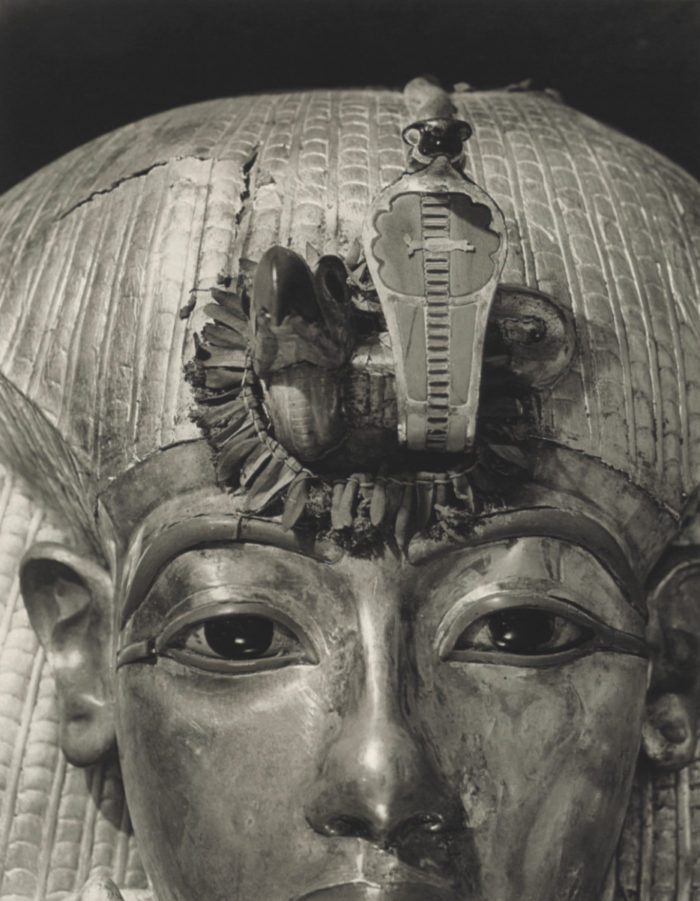

This was a tomb like no other, still full of its owner’s funerary treasures. 5398 objects were cleared in all, making it one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in history. Had Carter given up hope or not been so persistent—and so persuasive—Tutankhamun’s tomb might still lie undiscovered.

Tasha Alexander is the author of the New York Times bestselling Lady Emily mystery series. The daughter of two philosophy professors, she studied English literature and medieval history at the University of Notre Dame. She and her husband, novelist Andrew Grant, live on a ranch in southeastern Wyoming.