by Nev March

The Spanish Diplomat’s Secret, the third book in my Captain Jim and Lady Diana series, is set aboard an 1894 steamship, the Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Etruria. Why the Etruria? As I researched the ship—and her sister ship the Umbria—I learned about their incredible real-life adventures and was immediately hooked.

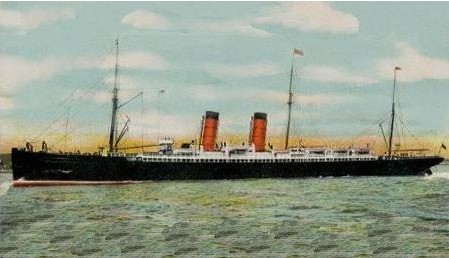

RMS Umbria and her sister ship RMS Etruria were built in a Glasgow shipyard and had their maiden voyages in 1884. They were the last two Cunard Line ocean liners fitted with auxiliary sails, which unfurled to take advantage of transatlantic winds.

This also meant they kept a contingent of sailors to climb the rigging and trim sails. The ships had three masts, but their single screw (think propeller) was driven by steam from coal-fed boilers. Down in the stokehole, thirty-six brawny stokers fed furnaces three hundred and twenty tons of coal daily—a prodigious amount for each journey.

As ship technology advanced, the newer, double-screw steamers eventually outpaced the Cunard pair. Ships got faster, commercial air transport took flight and these achievements faded from our collective memory. However, reading about the adventures of these two ships and the precarious nature of early commercial travel continued to shock me.

During an outbound journey in December 1892, the Umbria was due at New York on Christmas day. She did not arrive. Three days later there was still no sign of her, and speculation grew that she’d sunk with all aboard. However, on the 29th, the steamship Galileo docked, bringing good news. She had passed the Umbria showing three red lights, which meant she was disabled but being repaired.

When at last, the ship limped into New York on 31st December, her delay was explained. In the middle of a high gale, the main propeller shaft had broken, leaving the ship helpless and drifting. Stranded on a wild ocean, the passengers must have been terrified. Incredibly, the Chief Engineer and his crew managed repairs amid heavy seas and saved the ship.

The flaws of single-shaft technology became even more apparent in 1902 when sister ship Etruria also lost her propeller and tried to reach the Azores by sail alone. Eventually, she was rescued by the SS William Cliff of the Leyland Line.

Among other remarkable stories surrounding these sister ships was a failed bomb plot. After the Boer War, when the ships returned to transatlantic runs, the Umbria was preparing to sail, when the New York Police Department received an anonymous letter claiming that a bomb was aboard When the ship was searched, a bomb containing a hundred pounds of dynamite and a crude timed fuse was found. It was discovered to be a mafia plot to down competing British shipping lines.

I was charmed to learn that in his youth, Britain’s future Prime Minister Winston Churchill had sailed on the Etruria. 20-year-old Churchill traveled to Cuba in 1895 to witness the Cuban war of independence against Spain, (his idea of a vacation!) taking the Etruria to New York as well on his return to Liverpool.

Early steamships played a crucial role in the growth of commercial cruising, which so many of us enjoy today. The juggernauts of their time, today these ships seem quite small. However, monthly transatlantic runs between Liverpool and New York by ships like these gave birth to the golden age of sea travel, connecting our continents and opening up our world to trade and travel. I hope you enjoy the opulence, charm, and dangerous excitement of these early steamers in The Spanish Diplomat’s Secret.

Nev March is the first Indian born writer to win the Minotaur Books/Mystery Writers of America First Crime Novel Award for her Edgar-finalist debut, Murder in Old Bombay. After a long career in business analysis, she returned to her passion, writing fiction. Nev sits on the NY chapter board of Mystery Writers of America and is a member of Crime Writers of Color. A Parsi Zoroastrian, she lives with her family in New Jersey and teaches occasionally at the Rutgers University Osher Institute.