by Linda Castillo

If you’ve traveled to Holmes County, Ohio, you’ve probably seen the quaint farms with the iconic bank barns and corn silos, the horse-drawn buggies, the men with long beards and flat-brimmed hats, and the women clad in below-the-knee dresses, their heads covered with organdy prayer “kapps.” Holmes County is home to the second largest population of Amish in the world, a hair behind Lancaster County Pennsylvania. It’s the heart of traditional America and chock full of bucolic scenery like covered bridges and fields plowed with horse-drawn equipment. It’s one of the prettiest and most unique destinations in the U.S.

Over the last few years, we’ve been subjected to movies and various reality shows ostensibly depicting the Amish and the plain life. But what do we really know about the Amish?

To know a people, you must first know their history. Amish history is fascinating and rich and, at times, shockingly brutal. No, they’ve never been violent. Quite the contrary; the early Amish—even today’s Amish—practice “nonresistance” which basically means they are pacifists. Hostility toward them is never met in kind. They will not defend themselves, nor will they defend their property. In times of war, the Amish are conscientious objectors and the men who served were often assigned civilian type roles that did not include the violence inherent to war.

Where did the Amish come from?

The Anabaptist movement began in sixteenth-century Europe during the Reformation. In 1527, Catholic monk Michael Sattler left the monastery and became an Anabaptist evangelist. He wrote what would later become known as the Schleitheim Articles, which basically outlined the Swiss Anabaptist view, some of which include nonresistance, separation, the bann, and adult baptism. In the end, Sattler was captured, tortured in the most horrific ways, and burned at the stake. The seven Schleitheim articles lived on and are still some of the fundamental ideologies of the Amish today.

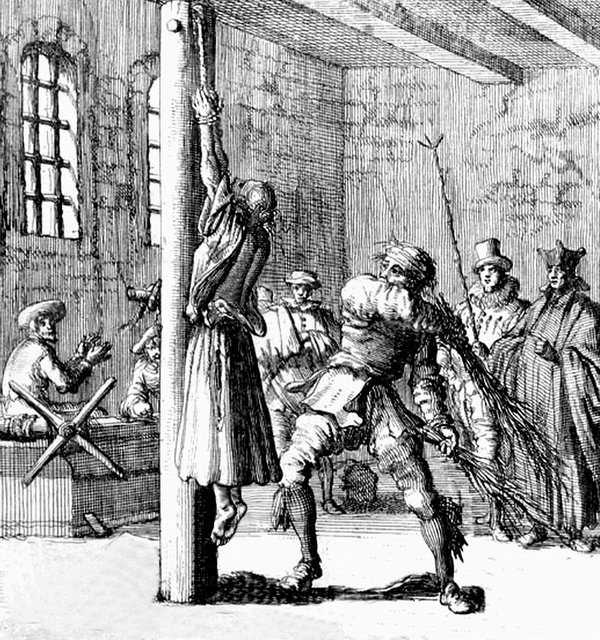

Because of their religious beliefs, the early European Anabaptists were mercilessly persecuted for being “nonconformists.” In fact, there was a secret police force called the “Anabaptist Hunters” that was formed by some of the cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy to find and arrest them. Once captured, the Anabaptists suffered terrible fates. Their land was confiscated, they were banished or tortured and sometimes executed for their crime of nonconformity, including being burned at the stake, hanged, or drowned.

Torture of teacher Ursula, Maastricht, 1570, detail of a copper engraving by Jan Luyken (1649-1712) from Martyrs Mirror. Image is in the public domain via Wikipedia.

Some of the personal stories of those early Anabaptists are brought to life in Martyr’s Mirror, a tome of nearly 1200 pages that was first published in Holland in 1660 by Thieleman J. van Braght. To this day the book is kept in Amish homes and has been translated into German and English. One of the stories contained in the book is that of Dirk Willems, an Anabaptist who was captured and imprisoned. While in captivity, Willems managed to forge a rope of sorts from pieces of cloth he tied together. He used it to climb down the wall from his prison cell, and he escaped. As he was running away, he crossed a frozen pond, making it to the other side. The man pursuing him, a guard, fell through the ice. As the cold water enveloped him, the guard cried out for help. Instead of running away and saving his own life, Willem went back to help the guard and saved the other man’s life. His selfless heroics were not rewarded. Willem was recaptured and later burned at the stake.

Three distinct groups emerged from the Anabaptist movement and still exist to this day: the Mennonites, the Hutterites, and the Amish. Jacob Ammann is credited with being the founder of the Amish. He was born in Switzerland in 1644. The date of his death is either disputed or unknown.

Because of continued persecution, many European Amish were forced to worship in secrecy. But Pennsylvania, thanks to Quaker William Penn, had a reputation for religious tolerance. It’s unknown when the first Amish migrated to North America, but the first “Amish ship” called Charming Nancy arrived in Philadelphia in 1737 and, lured by land, the Amish settled in small communities in and around Lancaster County Pennsylvania. The first known settlement was Northkill in Berks County and probably housed about 200 people. But an Indian attack left several Amish dead and the settlement was abandoned. The only thing that remains today is a historical marker.

Between 1816 and 1860, a second wave of Amish immigrated to North America, this time arriving in Baltimore and New Orleans. These Amish had learned that their predecessors were now prospering—and free from religious persecution. These immigrants settled mostly in Ohio’s Holmes County and surrounding areas.

Sadly, no Amish congregations exist in Europe. The ones that remained either lost their Amish identity or merged with the Mennonites.

The Amish have flourished in the U.S. According to a study by the Young Center for Anabaptist Studies, Elizabethtown College, the Amish population in the U.S. stands at 324,900. They’ve preserved their way of life, the religion so many of their forebearers suffered and died for, and they’ve upheld the traditional values of their forefathers.

So, the next time you’re cruising down the road in Holmes County and come upon an Amish family traveling in their buggy, give them a smile and friendly wave. Let them know we’re glad they’re here, and that all of us are free to live our lives and worship as we choose.

Citation: “Amish Population, 2018.” Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College. Check this for the reference

Reference: “Amish Society” by John A. Hostetler

LINDA CASTILLO is the New York Times bestselling author of the Kate Burkholder novels, including Sworn to Silence, and most recently Shamed (July 2019). She is the recipient of numerous industry awards including a nomination by the International Thriller Writers for Best Hardcover, the Daphne du Maurier Award of Excellence, and a nomination for the RITA. In addition to writing, Castillo’s other passion is horses. She lives in Texas with her husband.