by Mariah Fredericks

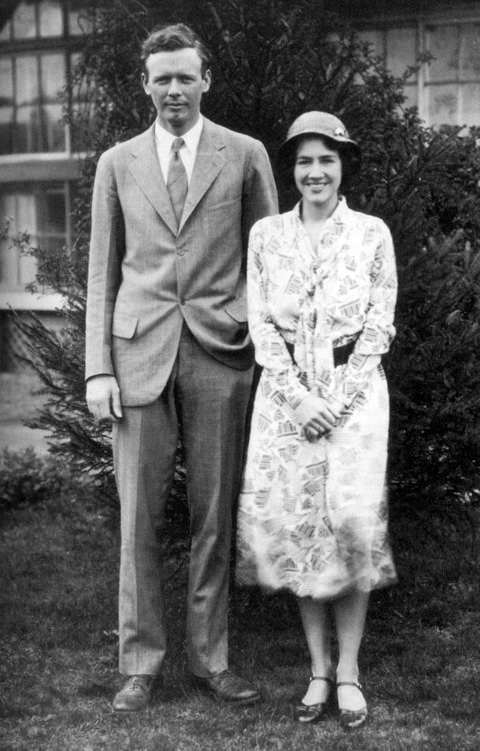

The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr. shocked the world in 1932. Mariah Fredericks, author of the recently released novel The Lindbergh Nanny, joins us to discuss the moments leading up to the kidnapping, and the relationship between the Lindberghs and their nanny Betty Gow, who quickly became a suspect.

When her first son, Charles Lindbergh Jr., was born on June 22, 1930, Anne Morrow Lindbergh wasn’t sure she wanted a nanny. Her own mother, Elizabeth Cutter Morrow, was a dynamic woman, heavily involved in philanthropy, education, and her husband’s political career. The Morrow children were often left in the care of others. In the words of Anne Morrow Lindbergh biographer Susan Hertog, “Betty Morrow was the perfect executive…she organized her children’s lives and left.”

Anne might have wanted something different, but she was married to Charles Lindbergh, a man not given to staying put on the ground for long. The Lone Eagle wanted to fly and he wanted Anne with him. She was not only his wife, but “crew,” a trusted colleague in his travels mapping prospective air routes. He was not going to be held back by parenthood—and neither was she. “He wants me to live my own life,” she would write years later. “He wants this so passionately that it angers him when he sees anything frustrating it.” In 1930, the parameters of Anne’s “own life” were defined by her adored and domineering husband. “The Eaglet” as Charlie was dubbed by the papers, would have a nanny.

Betty Gow, the young Scottish woman who would become the Lindbergh nanny, first met the famous aviators on February 23, 1931. They interviewed her in the hallway of Anne’s parents’ estate, a strange choice that indicates Betty was to be allowed in—but only so far. She did not care for Colonel Lindbergh, pronouncing him “nobody special.” But she liked Anne very much, finding her warm and unpretentious.

Betty was young and relatively inexperienced—certainly when it came to caring for the children of the rich and famous. She left the interview expecting never to hear from the Lindberghs again. To her surprise, she got the job the very next day. For the next year, the last of Charlie’s life, she was his primary caregiver for long stretches at a time, often the first person he called for, the only person besides his mother he clung to when approached by strangers.

Colonel Lindbergh believed that children should not be hovered over, a belief that was bolstered by the Watson method, a parenting theory in vogue at the time which firmly discouraged mothers from giving “too much love,” lest the child become weak and dependent. Betty recalled, “I was told not to cuddle him or make him too fond of me.” At times, she had a difficult time with the Lindberghs’ parenting approach. To strengthen the child’s self-sufficiency, Colonel Lindbergh built a pen out of chicken wire in the yard. He then placed the baby in the pen with a few toys and left him there for hours. When he cried, Betty appealed to Anne, who said, “Betty, there’s nothing we can do.” It’s unclear if she meant they could not defy the method or could not defy Colonel Lindbergh.

In the summer of 1931, the Lindberghs left on an expedition to Japan that would last three months. Anne said, “I would have been content to stay home and do nothing else but care for my baby. But there were those…flights that lured us to more adventures.” Or as Betty Gow would put it, “Oh, how she loved her Lindy. She’d have gone anywhere and done anything for him…even leave that beautiful little baby behind.”

With the Lindberghs away, Betty and the baby traveled with Anne’s parents to their vacation home in Maine. (“Don’t let people fuss over him or pay attention to his little falls and mistakes, will you?” Anne wrote to her mother.) Betty expected to return with the Morrows at summer’s end. But in August, Mrs. Morrow learned there was an outbreak of “infantile paralysis” in New Jersey; best if Betty kept Charlie in Maine. According to Hertog, this left Betty alone with Charlie for two months. The family hadn’t provided her money for expenses; she had to spend her own money on clothes when Charlie outgrew his old ones. She later said she felt abandoned by her wealthy employers.

But the resentment doesn’t seem to have lasted. When they returned, the Lindberghs, perhaps aware that she had gone above and beyond, gave Betty three months off. Anne was also eager to spend time with her son. This note from Anne encapsulates both the tension between the two women, but also a lovely spirit of understanding and comradery. “It is such a joy to hear him call for ‘Mummy’ instead of ‘Betty!’ And [Betty] understands just how I feel about it and helps me.”

Tragically, the gentle partnership was short-lived. On March 1st, 1932, Anne and Charlie were at the Lindberghs’ new house in Hopewell, New Jersey. Normally, they would have returned to the Morrow estate in Englewood by Tuesday morning. But Charlie had a cold, which Anne caught. Exhausted, she called Betty at Englewood and asked her to come. Together, the two women put Charlie to bed. It was the last time either of them would see him.

In a letter to her mother shortly after Charlie was taken, she wrote, “Mrs. Lindbergh has been very brave about it. She’s wonderful.” Betty soon found herself a suspect. Colonel Lindbergh was adamant in his defense of his staff; Anne’s feelings are less clear. When Lindbergh’s mother wrote an appreciative note to Betty, Anne thanked her saying, “It came just at the right time for she has had so much grilling and criticism and is such a loyal girl.” When Charlie’s body was found, Betty was asked to make the identification. It is understandable that the police wanted to protect the mother, who was pregnant with her second child. But it must have been a shattering experience for the young woman who cared so much for Charlie. Betty worked intermittently for the family after that, but she soon returned to Scotland, only coming back to America in 1935 to testify at the Hauptmann trial.

It seems inconceivable now that the Lindberghs ever suspected Betty of working with the kidnappers—but it wasn’t to her. In 1993, at the age of 88, she was interviewed by Lindbergh biographer A. Scott Berg. He told her that Mrs. Lindbergh sent her regards. At which point, “she just burst into tears.” After returning to Scotland, Betty had sent a letter to the Lindberghs. They never replied. For decades, she believed they hated her and blamed her for Charlie’s death.

The Lindberghs, of course, received thousands of letters. They moved frequently, and there is every chance that Betty’s letter never reached them. One might expect silence from the notoriously “unsentimental” Colonel Lindbergh. But I do wonder how a woman as exquisitely sensitive and perceptive as Anne Morrow Lindbergh was could have failed to understand that the young woman who cared for her child, who loved him dearly, would have needed to hear from his mother those simple words: it wasn’t your fault.

Mariah Fredericks was born, raised, and still lives in New York City. She graduated from Vassar College with a degree in history. She is the author of the Jane Prescott mystery series, which has twice been nominated for the Mary Higgins Clark Award, as well as several YA novels. She can be reached through her website.