by Daniel Torday

Revisiting Kent and Poxl West

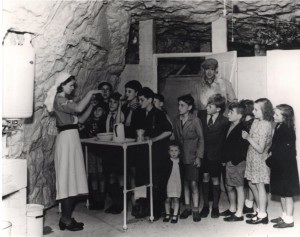

At some point during the years I spent researching the London Blitz in order to write key scenes from my debut novel, The Last Flight of Poxl West, I came across a line in a book that mentioned that thousands of Londoners had lived in caves in the Kent countryside to survive the bombing. First I’d thought, Oh, that would make for a nice scene in a novel—if I was a novelist I’d want to use that. Then I thought, Oh, right. I am a novelist. I should use that. As many as 15,000 civilians had moved to the Chislehurst Caves in the immediacy of the nine months of the Luftwaffe bombing of London in fall of 1940 and winter/spring of 1941. Some would move there again in 1944 when the Nazis were firing their V weapons from the French coast. The former I would just have to find a way to use in a novel that already had been drafted. It was too good not to. So I did, and I finished the book.

After eight years of researching and writing I came to feel a small confidence that no matter how much I’d gotten right, I’d at least reached a draft in which I’d not gotten anything egregiously wrong. I found an editor for the book on the strength of that draft. Then, while working on edits, I discovered that a colleague of mine was from Kent, the county southeast of London where I’d set those cave scenes. Her parents had grown up there during that time, and she would read it for me, consulting them as well.

I awaited my British colleague’s read with great trepidation. When I’d first encountered news of these caves in Kent—of really all the details I’d discovered regarding the Blitz—I’d simply attempted to get down scenes that would work in a novel. Now here were readers who carried their own memories of those very places. Would I have offended every one of their sensibilities? Had I torn holes in well-worn histories? What came back was perhaps more instructive. In a scene in which my main character, Poxl West, walked back toward the caves with his girlfriend, Glynnis, I had them being bitten by mosquitoes. This was 1941. My colleagues’ parents informed me that mosquitos, in fact, weren’t introduced to the region until the ‘60’s. I blushed, self-flagellated, then asked… so what would they have been bitten by?

Midges.

I did not know what a midge was, but I found and replaced “mosquitoes” with “midges.” A change of a single word in four or five places suddenly lent the scenes texture and, with luck, authenticity.

In an earlier scene during the Blitz, back in south London, I had Poxl West drinking a Boddingtons in a pub (I knew enough to call it a pub, not a bar). I thought my beer knowledge would recommend me—I’ve spent hours in bars on that “research”— but my colleague’s parents quickly set me straight: each publican would pull the ale or stout of his own bar.

I capitulated.

Poxl’s draught would have to be a generic draught.

Elsewhere in those caves I’d had a character ask another in dialogue if she was “mad,” meaning was she angry—my British-ism checkers reminded me that in the UK that colloquialism would have meant, “are you insane,” an implication I wasn’t looking for. These were the small details I’d been seeking, the fixes you can’t find in a book, the textures that move us from the broad strokes of history into the brushstrokes of a novel.

There was one place where my Kentish readers helped me and I stood my ground, and perhaps it is the place where I now see where I stand as a novelist. I’d not asked the right questions about those Kent caves I’d sent Poxl and Glynnis to in the book. I’d not gone to them myself—I’d read about them long after my physical research trips to the UK had ended. I’d used my imagination. I’d imagined natural caves, caves made of my imagination, dripping with stalactites and stalagmites. But my British guides quickly pointed me toward what, as I say, I now know were the Chislehurst Caves—easily Googleable. They’re still there today. But they’re not natural caves. They’re the remnants of chalk and flint mines, man-made, broad and so wide that in a later era Jimi Hendrix played a concert there. The Rolling Stones, too.

It would have been easy enough for me to recast those scenes, conforming them to dictates of historical accuracy, granting them their proper noun. But some novelistic urge kept me from doing it. There was some magic for me in that sentence or two that had sparked my imagination, sent me into those caves with Poxl. I didn’t want to lose that magic, what Nabokov referred to as the “shimmering go-between” from our world to the world of the novel. “That go-between, that prism,” Nabokov said, “is the art of literature.” So I thanked my colleague for saving me from mosquitoes, from Boddingtons, from madness. But I’d keep my caves.

DANIEL TORDAY is the Director of Creative Writing at Bryn Mawr College. The author of the novel THE LAST FLIGHT OF POXL WEST, a New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice and the winner of the 2015 National Jewish Book Award for fiction. Torday’s stories and essays have appeared in Esquire Magazine, n+1, The New York Times, The Paris Review Daily and Tin House. He is Director of Creative Writing at Bryn Mawr College.