by Elsa Hart

The Forbidden City is an iconic image of imperial power. Its imposing gate channels today’s tourists to a glimpse of China’s awe-inspiring dynastic history. The vast courtyards, towering pavilions, and exhibited treasures uphold a vision—pervasive in western imagination and suggested by its very name—of an entire domain consolidated within its massive walls.

It might be a surprise to learn that even early in the Qing dynasty, at the height of imperial supremacy, the Forbidden City was only one organ—albeit the heart—of a thriving urban capital. In the Inner and Outer Cities that surrounded the enclave of the emperor, ministries performed their administrative functions, nobility built their mansions, trade and industry bustled, and foreigners established their own communities. And at no time during this period was Beijing more animated and astir than during the tri-annual civil examinations.

In the weeks leading up to the tests, Beijing transformed. Thousands of hopefuls poured into the city. They arrived on horseback, carrying fluttering banners that identified them as candidates. Inns were quickly filled to capacity, as were temple guestrooms. In addition to servants and family members, candidates brought with them their anxieties and superstitions. Charlatans were quick to take advantage, offering to read fortunes and concoct potions that would increase a candidate’s chances of success. More legitimate vendors sold writing supplies and copies of previous examination answers.

For any man who aspired to become an official, passing the civil examinations was essential. To guarantee placements for those with degrees, a quota system limited the number of candidates who could pass each year to approximately two hundred. In the resulting atmosphere of nervous energy, the entertainment districts thrived. Among the diversions on offer were beauty competitions that invited candidates to play the roles of examiners, rank women according to their looks, and award them mock degrees. For a price, a candidate could request the reverse fantasy, in which a courtesan acted the part of his examiner. Alcohol flowed freely as first-time candidates exchanged rumors of what the inside of the examination yard would be like, and returning candidates fortified themselves for another grueling attempt.

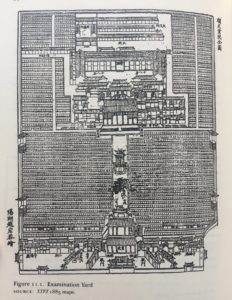

In the final hours before the exams commenced, commercial activity became concentrated around the examination complex located on the eastern edge of the city. Peddlers had one final opportunity to sell brushes, ink, food, and bedding before the candidates filed into the yard. Once inside, they were not permitted any contact with the outside world for three days. The complex contained thousands of identical cells divided by thin walls, but open to the sky. Within each tiny cell were two planks to be used as a seat, desk, and bed. More comfortable quarters were provided for the examiners and their clerks.

In the final hours before the exams commenced, commercial activity became concentrated around the examination complex located on the eastern edge of the city. Peddlers had one final opportunity to sell brushes, ink, food, and bedding before the candidates filed into the yard. Once inside, they were not permitted any contact with the outside world for three days. The complex contained thousands of identical cells divided by thin walls, but open to the sky. Within each tiny cell were two planks to be used as a seat, desk, and bed. More comfortable quarters were provided for the examiners and their clerks.

Upon entering, candidates were subjected to rigorous searches to ensure they had no hidden copies of the classics. For the next three days, they wrote their essays. If it rained, they huddled under oilskin blankets. Unlucky candidates were assigned to cells near the latrines, which exuded increasingly foul odors as the hours passed. Illness was not an excuse to leave—if a candidate died, guards passed his body through a hole in the outer wall. Nighttime brought the threat of fire, as candidates lit candles and continued their work. With thousands trapped inside wooden walls and locked doors, a blaze could easily claim hundreds of lives. Outside, the families waited.

After three arduous days, the candidates emerged to a new ordeal. It took weeks for the essays to be graded. When at last the results were posted, a new period of festivities began for the successful candidates. The experience of those whose names were not on the list of degree-winners is well described by the 18th-century writer Pu Songling, who wrote that the failed candidate “collects all his books and papers from his desk and sets them on fire; unsatisfied, he tramples over the ashes; still unsatisfied, he throws the ashes into a filthy gutter. He is determined to abandon the world by going into the mountains, and he is resolved to drive away any person who dares to speak to him about examination essays.” (Translation of Pu Songling from A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China by Benjamin A Elman)

Recommended reading:

Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400-1900 by Susan Naquin

Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio by Pu Songling

ELSA HART was born in Rome, Italy, but her earliest memories are of Moscow, where her family lived until 1991. Since then she has lived in the Czech Republic, the U.S.A., and China. She earned a B.A. from Swarthmore College and a J.D. from Washington University in St. Louis School of Law. City of Ink is her third novel.