by Eliza McGraw

The Sunny Man Mystery

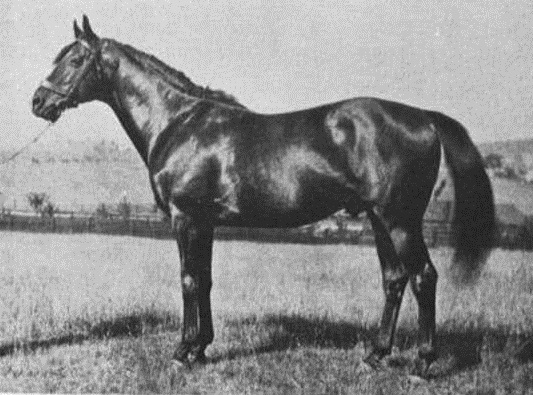

In May of 1925, a strong, beautiful racehorse named Sunny Man died in agony, thrashing in his stall, his lips turning blue. His death horrified horsemen, who were equally concerned with the idea that it had been intentional. Who or what killed Sunny Man?

The mystery of what happened to Sunny Man highlights a lot about horse racing in the 1920s, including the amount of money involved, the role of racehorse owners, and a very dark side of a glamorous sport. The case might have been a riddle, but it also illuminated some questions about racing. In the mystery of Sunny Man, there’s a kind of a distillation of the contemporary obsession with sports, how the press affected racing, and the frightening possibilities of what could become of a horse.

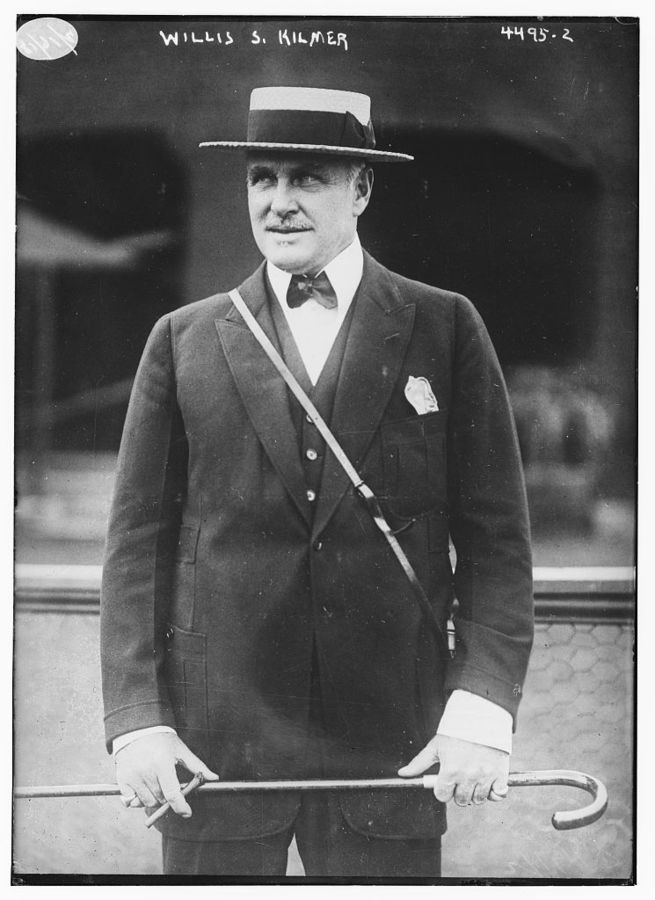

All early spring, Sunny Man looked good. Muscled, chestnut, and fast, he reminded people of his speedy sire, Sun Briar, and like his father he was a Kentucky Derby favorite. He had won three big races already. His owner, Willis Sharpe Kilmer, owned the 1918 Kentucky Derby winner, Exterminator, and Sunny Man looked like his best chance to have another in his barn. Kilmer was an outsized millionaire, a patent medicine magnate used to getting what he wanted.

But one day, he didn’t. Sunny Man turned in a bad race. He was fast in his workouts, but at post time, he slogged along and finished second in the six-furlong Carolina, behind a no-counter named Prince of Bourbon. The poor performance made sense when the colt seemed sick while he was being moved to Baltimore’s Pimlico after the Havre de Grace, Maryland meet. He spiked a fever, but then seemed to rebound the next morning. In the afternoon, though, the fever rose again, and Sunny Man worsened, until he finally died, legs churning in fruitless agony, his fine head disfigured.

Sunny Man’s trainer, John Smith, immediately told reporters that three veterinarians believed that the horse was poisoned. One thought that the horse had been given a pill made up of chloral hydrate—a sedative–and arsenic. Smith, who had watched Sunny Man die so horribly, thought so too. But he couldn’t figure out how anyone could have gotten to him, since two Kilmer watchmen had stood guard at his stall in Havre de Grace. In fact, Edward Burke, the manager of the Havre de Grace racetrack thought the idea so outlandish that would not take any responsibility, even though the alleged poisoning happened at the track under his control. He said, “If the horse was tampered with after these precautions”—he meant the Kilmer guards–“then there is nothing that we can do in the matter.” Kilmer would have to do his own digging.

But who would want to poison Sunny Man? And why? The 1920s was a time of spongers, who surreptitiously inserted sponges into horses’ noses to inhibit their breathing and dopers, who tried to speed horses up with different concoctions, but outright poisoning was unusual, and would have been brazen in the case of the guarded, famous colt. There was no shady rival to point toward, no notorious criminal who had a horse Sunny Man had beaten.

By May 4, newspapers reported that there would be two investigations into Sunny Man’s death. There was Kilmer’s, and then the insurance company—the colt was insured for $150,000–would also launch its own. (Another insurance number was that he was insured for $100,000 with Lloyds and $50,000 with Hartford.)

Kilmer countered these figures, telling the Washington Post that Sunny Man was actually insured for $45,000, not $150,00. Kilmer’s veterinarian and his trainer mocked the idea that the colt died from an accidental overdose of chloral. And Kilmer told the Post that he was despondent. He didn’t even know what he wanted to do next, in terms of racing. He said he felt the death of Sunny Man so much, he couldn’t figure out what his plans were.

Perhaps it was Kilmer’s uncharacteristic melancholy, or perhaps Nate Baxter, the Washington Post’s sports editor, had simply had enough of crookedness in racing, something he wrote editorials against. But he became particularly interested in the Sunny Man case. Editors at the newspaper supplied the next twist in the story, offering a $5,000 reward if anyone came forward with information that would lead to the arrest for the responsible poisoner.

Then, a ghastly detail emerged. One of the insurance investigators, Dr. Frank Ingram, went to examine the colt’s body and found that it had already been destroyed, thrown into an acid bath at a fertilizer plant. (He’d wanted to examine the stomach and other digestive organs.) The owner of the fertilizer company said he was just doing his job; city health ordinances said that any carcasses that came in should be destroyed as soon as possible. If Kilmer had wanted to delay, he said, he could have. But Kilmer had never asked.

The Maryland Jockey Club’s veterinarian, Dr. H. J. McCarthy, weighed in at this point. He’d never ordered the body taken away, he told Ingram. And anyway, he thought he knew what had caused the colt’s death. “I diagnosed the trouble as caused by a hypnotic medicine and told the stableman that the horse would not live but a few days,” he told the Washington Post’s reporter; he was in the too-much-chloral-hydrate camp. “I asked the boy about the medicine and he told me that he had given Sunny Man a sedative prescribed by Dr. Robert McCully, of New York. Sunny Man was not my horse, nor was he my case. I gave him a prescription to relieve him and told the stable man to send for Dr. McCully, who could probably prescribe an antidote for the medicine. Dr. McCully came to Baltimore on Wednesday. He made light of the case and said the horse would recover. I withdrew from the case then,” McCarthy said.

Trainer Smith’s story corroborated McCarthy’s. Smith also said that McCully was the one who took the medicine from the scene and also the one who ordered the body taken away.

So all three veterinarians—McCarthy, McCully, and Ingram—agreed that Sunny Man was poisoned to death. What no one could figure out was if it was malicious. Had the colt been slaughtered? Accidentally overdosed by the stableboy? Or was McCully himself at fault, for ordering an incorrect amount, or prescribing a faulty compound?

During all of this, Kilmer was at one of his Virginia farms. He said none of his other horses would race until the Sunny Man issue was cleared up. He was sorry he couldn’t say more, he told reporters, but he was waiting to see what the investigations showed. “I know nothing about the circumstances surrounding the death of Sunny Man except what I have read in the papers,” he said. “Insurance company investigators are now probing into the case, and I feel sure they will render a complete report within a day or two.” Kilmer said he had received many sympathy messages, and that his employees were as sad as if one of their own family members had died.

The Washington Post continued to advertise its reward, an atypical move, as the Post itself reported. The gesture was meant to spur officials to clean up racing, and highlight how little officials were doing. “Turf followers all over the East will realize that a private effort is being made to solve a crime in which racing officials ought to be interested but have not, according to their own admission, made a move,” wrote sports editor Baxter. And the plan seemed to have some merit, because a reader wrote in, “That’s the spirit—go to it and you will have every lover of clean racing back at you. You newspaper folk can ravel out murder mysteries, and this is a murder—pure and simple—in the first degree.”

But no newspaper folk—nor anyone else–ever discovered exactly what happened to Sunny Man. Not only that, but in the end, it did not seem like it really was a murder mystery as much as a case of neglect, or ignorance gone wrong. There is the explanation is that either McCully gave bad instructions to the stableboy, or that he accidentally prescribed an overdose of chloral. Then McCully insisted that the horse was poisoned—and let the stableboy be blamed–because he didn’t want anyone to know that he’d actually been responsible. Or, perhaps he really was poisoned by a potential rival. In any case, as the Post’s Nate Baxter wrote, “There are many avenues open to official feet that others cannot follow. It is stupid to deny that cause for investigation exists. Action should be taken no matter where the responsibility for the death of Sunny Man may rest.”

But specific action was never taken. We still don’t know where the responsibility for the death of Sunny Man should rest. Even today, it’s one of racing’s unsolved mysteries. The $10,000–$5,000 from the Post and $5,000 from Kilmer—went unclaimed. Worse, there’s no tangible way to say whether Sunny Man’s death changed racing.

Even without tangible answers, though, this moment in 1925, with horse death labeled murder, and a newspaper rallying to solve a crime—was important. A horse died, and people cared.

ELIZA MCGRAW is the author of HERE COMES EXTERMINATOR!: The Longshot Horse, the Great War, and the Making of an American Hero, as well as a contributing writer for EQUUS magazine and author of two instructional equestrian books as well as two academic works. Her horse-related writing has appeared in The Chronicle of the Horse,The Blood-Horse,Mid-Atlantic Thoroughbred, Raceday 360, the New York Times’ racing blog, and The Washington Post. She has taught at American University and earned degrees from Columbia University and Vanderbilt University. She lives in Washington, D.C., with her family, and keeps her paint mare Sugar in Potomac, Maryland.