by Greg Jenner

Brushing our teeth at 11.45 p.m.

Dragging our leaden feet up the staircase, we look longingly at our bedroom door. But, before we can clamber gratefully under the duvet, a nagging voice in the back of our head demands that we complete one crucial daily ritual, the one our parents always made us do, no matter our protestations. It’s time we brush our teeth.

WHITE TEETH

We’ve reached the point where celebrities’ teeth are eerily radiant slabs of alabaster showcased in perfectly carved symmetrojaws. Teeth have been elevated beyond their biological purpose of food mashing to become aesthetic fashion statements. But for virtually all of human history, they were primarily functional chewers without which our ancestors would have starved to death. And starving was sometimes a genuine possibility, as the challenge wasn’t to maintain the blinding radiance of a kilowatt grin, but simply to keep one’s teeth vaguely proximal to the lower half of one’s face. Teeth are sturdy little blighters but over time they’re naturally susceptible to bacterial infection, gradual wear and tear, blunt-force damage and acidic decay. In short, they can fall out.

So, given the necessity of tooth-care, it’s not that surprising that the story of dentistry begins in the Stone Age.

NEOLITHIC GNASHERS

The pain was sharp, a fierce buzz that ricocheted down through his body all the way to his toes. He kicked his heels against the floor in frustrated protest, angry at having to endure this torment, but remained flat on his back – the last thing he wanted was for the drill to slip from its user’s grasp and plunge into the soft tissue of his tongue. The dentist loomed over him, sawing back and forth like a lumberjack, with an expression of intense concentration. The sound of the drill grinding against the decayed molar reverberated through the patient’s skull, a quiet whittling to accompany his muted winces of pain. The patient closed his eyes, and thought of something else. It would all be over soon. And within a minute, it was.

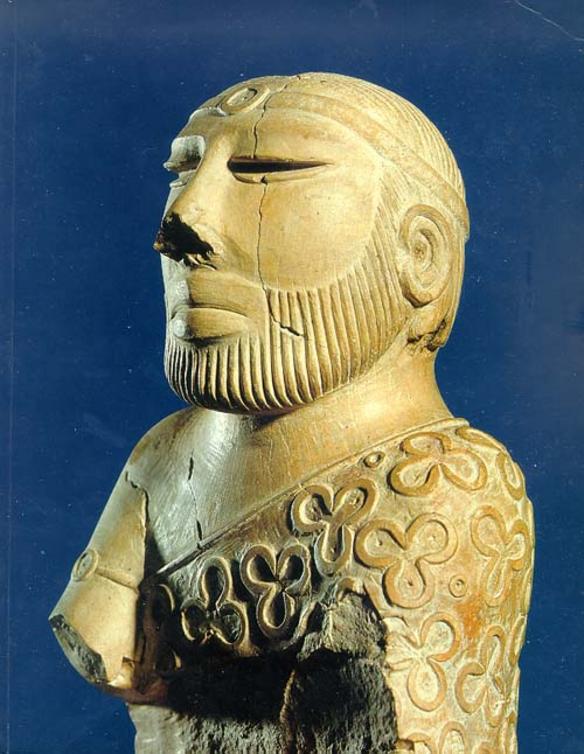

Nine thousand years ago, at a place called Mehrgarh in modern Pakistan, possibly the world’s first dentist was plying his or her trade thousands of years before the blueprints for Stonehenge were even being drawn up. This seems one hell of a claim, but the evidence is visible in the teeth of skeletons found in the remains of this Neolithic town. To the ordinary eye, tiny holes of 0.5–3.5 mm depth aren’t terribly impressive, and we probably wouldn’t even notice them at first glance, but to archaeologists their uniform shape is unmistakably proof of dental drilling. More than 5,000 years before anyone was wielding malleable metal tools, this dentist used a flint-tipped bow-drill to quickly burrow through enamel into the pain-causing caries. Typically used to puncture eyelets in jewelry beads, the sharpened flint would have been fixed into a wooden shaft which was then looped with string and attached to what looks like an archer’s bow, so that by dragging the bow back and forth – as if sawing a piece of wood – the shaft would rotate clockwise and counter-clockwise on its axis, gouging a tiny hole in the tooth.

But how do we know this was therapeutic dentistry, rather than some religious ritual or an ill-advised fashion statement? Of the 11 drilled teeth discovered at the site, at least four were afflicted by inflamed caries, and the fact that only rear molars – lurking in the hidden recesses of the cheeks – were operated on probably quashes any notion of this being some sort of snazzy smile modification. If you’re gonna spruce up your grin, surely you want the design to be front-facing? Given that caries cause sharp pain, it’s much more likely that this procedure aimed to alleviate chronic toothache. Intriguingly, drilling wasn’t the limit of a prehistoric dentist’s powers. An Italian team of boffins has recently proven that a skeleton found in Slovenia, the remains of a young man who died about 6,500 years ago, boasted what seems to be the world’s first filling – a beeswax resin poured into a cracked tooth. Whereas the drilling in Mehrgarh had presumably been to scoop out an infected cavity, this was apparently designed to encase an exposed nerve.

So, despite modern dentistry being a high-tech business with X-rays, lasers and electronic gadgets, what remain our most common treatments – fillings and drillings – date back thousands of years. What’s more, our dentist will tell us that sugary foods are enemy number one, and this too was a familiar issue for our prehistoric ancestors. The Neolithic farming revolution led to greater consumption of starchy foods, such as bread and porridge, increasing the level of natural sugars in the mouth and thereby inviting cavities and acid erosion to do their worst. But the chief destroyer of ancient dentine was the abrasive coarseness of grit lurking in the loaves, an unfortunate by-product from grinding flour on quern stones.

Perhaps the most famous early victim of this dental attrition was our long-dead pal Ötzi the Iceman, the Neolithic murder victim from Tyrol. His teeth were in a terrible state: discolored, smashed up in places, worn down in others. He’d lost a cusp on one molar, probably from enthusiastically chomping on a stony loaf, and serious damage

to one of his front teeth suggests someone, or something, had smacked him violently in the face. The fact that he later wound up with an arrow in his back suggests he wasn’t one of those lovable Tom Hanks types. While Ötzi was perhaps particularly unlucky, his mouth was broadly representative of normal dentition in prehistory. Teeth aren’t invulnerable, and by the end of a Neolithic person’s life, even in their forties, their attempt at a Tom Cruise grin would have more likely resembled the aftermath of detonating a tiny grenade in the movie star’s mouth – there would still be teeth, but it sure wouldn’t be pretty . . .

THE TROUBLE WITH TOOTH WORMS

Miniature rocks and natural sugars may have been the true culprits, but the scapegoats who took the blame were far more sinister. As the Bronze Age arrived, both Babylonians and Egyptians developed a strongly held belief in monstrous little creatures called ‘tooth worms’, thought to spontaneously generate in the mouth like the re-spawning ghosts in Pac-Man. It was a theory perpetuated by the Romans and still in vogue during the eighteenth century, which meant dentists spent millennia conjuring up treatments for critters that didn’t actually exist.

Accordingly, the Bronze Age response to toothache often involved superstitious incantation: the Babylonians donned protective magical amulets and, if the dastardly worms showed up, implored the great god Ea/Enki to destroy them. If that failed, a dentist might smoke them out. By 2250 bce, oral fumigation – burning henbane seeds, kneaded into beeswax, near the mouth – was the established treatment and once the wriggly enemy had been slain the cavity was filled with gum mastic and more henbane. Yet, despite the early promise of Neolithic drill technicians, the Babylonians weren’t ones for surgery or fillings. Their dentistry was surprisingly low-tech.

Greg Jenner is a British public historian best known for his work as historical consultant and cowriter on the BBC’s multi-award-winning comedy series Horrible Histories. After studying at the University of York for a BA in history and archaeology, and an MA in medieval studies, Jenner has worked in the TV industry on award-winning historical documentaries, dramas, comedies, and digital interactive projects for the past eleven years. He lives in the United Kingdom. He is the author of A MILLION YEARS IN A DAY: A Curious History of Everyday Life from the Stone Age to the Phone Age.