by Jeff Katz

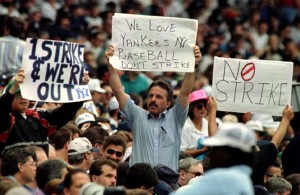

Those who think Major League Baseball is simply about the play on the field are too romantic and those who think it’s only about the business off the field are too cynical. The truth is somewhere in between and no season shows that better than the Split Season of 1981, unforgettable for the rise of rookie phenom Fernando Valenzuela, the insanity of George Steinbrenner’s Yankees, the drive and ambition of Pete Rose’s pursuit of the all-time National League hit record and the last World Series match-up of the Yankees and Dodgers. It was historic year off the diamond, with the first mid-season strike in sports history.

When the strike came on June 12, 1981 I was heartbroken. It would have been unfathomable to that almost 19-year-old me that I would one day speak with, and meet, the principals of the day.

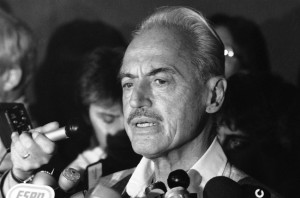

Talking to your idols is the strangest thing. When I called Marvin Miller, the Executive Director of the Players’ Association, and a man I truly admired, I was amazed how even in his nineties, he had such a wonderful memory and was flawless in his recollection. As I looked at decades old articles laid out before me, Miller was confirming or embellishing as if he had the same pieces in front of him. It was amazing.

More than Miller, the players were the symbols of the sport/business dichotomy, playing ball before and after the strike and, especially for those deeply involved in the negotiations, fighting a righteous and principled cause. The union pushed back on the owners’ attempts to crush the newly gained rights to free agency that players received after an arbitrator’s ruling in 1975. Before that decision, major leaguers could never do what every other American took for granted, to seek employment wherever they wanted to.

The owners misread their players, thinking they were still dumb jocks, throwbacks to a simpler time, and underestimated the players’ unity and belief in their position. Oddly enough, team owners missed the obvious, the essence of these men who were trained to win. The owners were shocked to find the same passion off the field as they expected on it. Tom Seaver, the Cincinnati Reds superstar pitcher in the midst of a stellar 1981 season, and seen by both sides as a thoughtful, moderating force during the tense negotiations, told reporters “The owners are taking a very destructive position; it’s very disturbing. If they are trying to alienate the players, they are doing a good job. But,” he warned, “they are working with competitive individuals.”

I got to witness this spirit first hand as I interviewed key players from 1981, players who not only excelled between the foul lines but who participated in the often heated talks that dragged on after the season was stopped in its tracks. What’s lost today in the facile take that “players are greedy and in it only for the money,” is that, in 1981, players were struggling to maintain the recently arrived at status quo. Protecting free agency was a serious and moral issue for them.

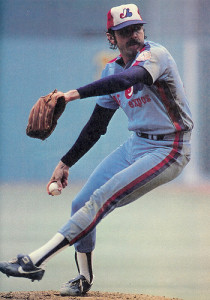

Steve Rogers, one of the four main player-negotiators and pitching ace of the Montreal Expos, spent hours with me on the phone, explaining the ins and outs of the negotiating sessions. If I got something wrong, Rogers set me straight and very directly. I felt as though he’d thrown a fastball under my chin, but it made me realize how important it was to the players involved that I got the story right. They’d put a lot on the line – their playing time, which is always at risk due to career threatening or career shortening injury, their money, and their image. Rogers spent much time away from his family during the nearly two months of the strike that eventually wiped 712 games off the schedule before it was settled. Subject to fan abuse, fans who were mostly fed the “money grubbing players” line by the press, Rogers found his luggage mutilated on a return trip to Montreal, a knife cut though the leather bag.

The strain of 1981 is still fresh for those who were there. Rusty Staub was often at the New York negotiations. The Mets had brought him back before the season began. Staub had no patience for the word games of owner’s lead negotiator Ray Grebey and flaunted his disdain by handing out New York Times crossword puzzles. I ran into Staub at a Cooperstown party last year and talked with him about 1981. Let’s just say that Rusty still harbors strong feelings about Grebey. When I mentioned I’d visited Grebey at his house in Connecticut a few years before his passing, Staub got angry enough at the mention of his name that I felt the need to apologize for bringing back bad memories. Still, it was another clear demonstration of what’s missing from the public perception: the players are committed to their beliefs and stay that way over the decades.

Researching Split Season:1981 gave me more insight into baseball, in ways I could never have expected. I found that in getting serious, with questions of depth and importance that strike to the heart of what it really means to be a professional major league baseball player, both on and off the field, there’s so much more to learn and be entertained by.

Jeff Katz is the Mayor of Cooperstown, the “Birthplace of Baseball” and home to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. He is the author of The Kansas City A’s & The Wrong Half of the Yankees. He was a featured speaker during a “New York baseball” program put on by The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, NY. He is a member of The Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). Split Season: 1981: Fernandomania, The Bronx Zoo and The Strike That Saved Baseball (Thomas Dunne Books) will be released on May 19. You can find him at Jeff-Katz.com and @splitseason1981.