By Timothy Stanley

It is hard not to think about the relationship between Hollywood and politics and not chuckle. The idea of Clint Eastwood talking to an empty chair at the 2012 Republican convention or Sean Penn giving acting classes in socialist Venezuela shrieks of self-delusion. But in reality, the movie business has seriously changed the way politics operates and how we think about it. Here are seven surprising things it’s accomplished (for better or worse):

1. Hollywood informed the Kennedy mystique. Jack Kennedy wasn’t born a presidential candidate, he was made one. Joe Kennedy, his terrifying father, had worked in Hollywood and understood the power of glamour—so he sent Jack out there in the 1940s to have dinner with Gary Cooper and learn how to look and behave like a star. JFK was unimpressed with Cooper’s personality—he quickly discovered that makeup, lighting and good publicity can turn the most mundane person into an idol. And so the JFK show was born.

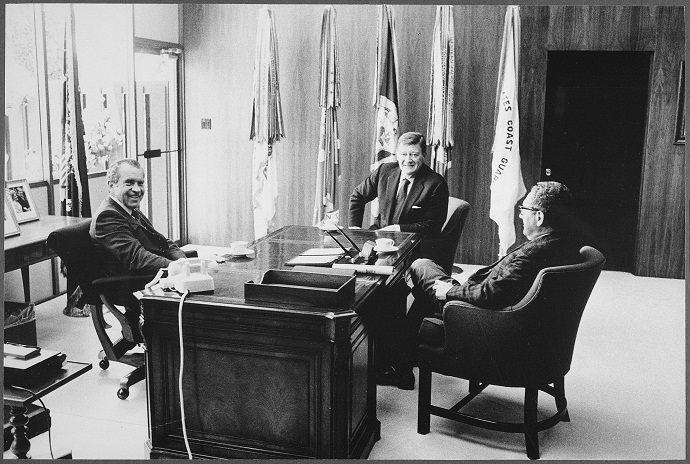

2. John Wayne helped Richard Nixon invent the myth of the Republican cowboy. In 1968, Nixon’s people surveyed the voters and found that humdrum Middle Americans were big fans of The Duke. So Tricky Dick started name-dropping him in speeches, redefining his presidency as that of a sheriff bringing law and order to the chaotic streets of America. The two men became good friends; Wayne stayed loyal to Nixon throughout Watergate until it became impossible to deny that the president had lied.

Nixon and Kissinger meet with John Wayne. Source: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration via Wikimedia Commons.

3. The stars have brought down presidents. Eugene McCarthy’s anti-war candidacy in the 1968 Democratic presidential primaries wasn’t expected to do very well, until his campaign struck upon the idea of sending out stars to canvass ordinary voters. The people of New Hampshire were surprised to open their doors to Dustin Hoffman and Paul Simon, while Paul Newman’s speeches really put McCarthy on the map. McCarthy’s people credited Newman in particular with generating the publicity that helped their man take 42 per cent of the vote—drawing Robert Kennedy into the race and forcing Lyndon Johnson out.

4. Hollywood was partly responsible for Obama’s endorsement of gay marriage. Days before the president backed legalization, reports indicated that his Hollywood donations were down—that movie people were holding back out of his lack of action on LGBT issues. At that point, one in six of his “bundlers” (people collecting several big money donations) was gay and Obama was in danger of losing their support. So the president announced that he supported gay marriage and—as if by coincidence— jetted off to Beverly Hills to raise new, huge sums of cash at George Clooney’s house.

President Obama meets with George Clooney in the Oval Office. Source: The Official White House Photostream via Wikimedia Commons.

5. Hollywood has helped presidential candidates define themselves as superheroes. The presidential candidates flirted with this in 2008, when Obama and John McCain were invited to choose which comic book character they best resembled. Obama went for Spiderman, McCain for Batman. But in 2012 it was the president who was recast as the caped crusader when The Dark Knight Rises set Batman against a character called Bane, which is eerily similar in name to the company that Mitt Romney founded. In this way, Hollywood helps define contests as battles between giants rather than serious dialogues about policies and ideas.

6. Hollywood fostered the impression that Democrats are elitists. The effects of George McGovern’s 1972 candidacy for the presidency are still being felt; it helped paint liberals as socially permissive, far out elites lacking in self-awareness. McGovern surrounded himself with movie star activists who played a public role in his campaign—siblings Warren Beatty and Shirley MacLaine were very much on board. But while MacLaine brought in big money, she also talked about reincarnation, Maoism as cure for America’s ills, and her novel idea of taxing diapers to stop women having so many babies. The voters were not impressed and the far-Left label stuck to many Democratic candidates for a long time.

7. Hollywood created the template of Obama’s presidency with The West Wing. The symbiotic relationship between the modern Democrats and Sorkin’s political TV show is extraordinary. On the one hand, many Obama staffers testify that they are huge fans and for them Jed Bartlet is a president to aspire to. On the other hand, the show’s writers actually based the character of Bartlet’s successor, Matt Santos, on a then little known Illinois senator called . . . Barack Obama. In fact The West Wing’s reach extends even to Burma, where politicians once told Hillary Clinton that in order to learn how to build a democracy they were rewatching old episodes.

Hollywood’s everyday influence is shown in friendships between movie makers and politicians, some of which have been intimate. Louis B. Mayer was so close to Herbert Hoover that he was the first person to stay in the White House after the Republican won the presidency in 1928. Its impact is also there in money, too, making a crucial difference at the start of Ronald Reagan’s career or helping establish Bill Clinton as a front-runner in 1992. But, most of all, it has helped to shape the imaginations of Americans and given them a sense of what politics ought to be about in both style and substance. The modern politician is a star playing an archetype: rugged individualist, superhero, matinee idol. It is partly the pressure to conform to the standards of Hollywood that keeps Washington DC so grindingly partisan—a battle between conservative cowboys and liberal idealists. And it has helped blur the lines between fiction and reality, encouraging statesmen to behave as though they were starring in a movie rather than just trying to pass bills or balance the books. Anyone who experienced eight years of California being run by Arnold Schwarzenegger—AKA The Governator—will confirm that what works on film isn’t necessarily the best recipe for running a government.

TIMOTHY STANLEY has spent time as a research fellow at Harvard and Oxford. The author of two books, Kennedy vs. Carter and The Crusader, and coeditor of Making Sense of American Liberalism, he has written political commentary for the National Review Online, The Atlantic, Dissent Magazine, New Republic, and CNN.com and is a columnist for the Daily Telegraph. His latest book is Citizen Hollywood.